Dick Smith (entrepreneur)

Richard "Dick" Smith | |

|---|---|

Smith in 2013 | |

| Born | Richard Harold Smith 18 March 1944 Roseville, New South Wales, Australia |

| Education | North Sydney Technical High School |

| Known for | Entrepreneur, aviator[1] |

| Spouse | Philippa Aird McManamey[2] |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Companion of the Order of Australia |

Richard Harold Smith AC FRSA (born 18 March 1944) is an Australian entrepreneur and aviator.[1] He is the founder of Dick Smith Electronics, Australian Geographic and Dick Smith Foods. Smith has had a long interest in aviation and holds a number of world records in the field. A major philanthropist, he supports a number of charities and conservation efforts.

In 2015, he was awarded the Companion of the Order of Australia.[3] He is a fellow of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry.[4]

Early life[edit]

Smith's father was a salesman and sometime manager at Angus & Robertson's bookstore. He started a business that failed when Smith was 17.[5] His mother was a housewife and his maternal grandfather pictorialist photographer Harold Cazneaux.[6]

As a child, encountered in serious academic difficulties and, having a speech defect, called himself "Dick Miff".[7] From his home in East Roseville, Smith attended primary school at Roseville Public School at which, for the fifth grade, he ranked academically 45th in a class of 47.[8] He attended North Sydney Technical High School. After three years of French, he managed only 7% in the Intermediate Certificate examination. He went on to complete his Leaving Certificate in 1961.[5]

He joined the 1st East Roseville Scout Group as a Wolf Cub in 1952, aged 8 and later as a Boy Scout and Rover until 1967, earning the Baden-Powell Award in 1966.[9]

Smith gained his amateur radio licence at the age of 16. He holds call sign VK2DIK.[10][11] In his early 20s, Smith worked as a taxi radio repair technician for several years.[8]

Business ventures[edit]

Electronics[edit]

In 1968, with a A$610 investment by him and his then-fiancée Pip,[8][12]: 203 Smith founded Dick Smith Car Radios, a small taxi radio repair business in the Sydney suburb of Neutral Bay, New South Wales, then later expanded into the car radio business at Gore Hill, naming himself the "Car-Radio 'Nut'".[13] This business later became electronics retailer Dick Smith Electronics which grew rapidly in the late 1970s, particularly through sales of Citizens Band radios and then personal computers, with annual sales of about A$17 million by 1978.[12]: 176

Smith took the business into Asia in 1978, opening a store in Ashley Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong's tourist shopping hub, and publishing an international catalogue edition until the store closed in 1980. That year, stores were also opened in Northern California and Los Angeles.[citation needed]

In 1980, he sold the business to Woolworths[14]: 35 for A$25 million.[15] Though Smith retained no shares nor role in the company after 1982, the business continued to trade with his name prominently displayed in every aspect of its operations. Sales reached A$1.4 billion in 2014,[16] before a sharp decline and closure of its then hundreds of stores in Australia and New Zealand by May 2016.[17]

Publishing and film[edit]

Australian Geographic[edit]

In 1986, Smith founded Australian Geographic Pty Ltd, which published the Australian Geographic magazine, a National Geographic-style magazine focusing on Australia. Smith did not want to greatly expand Australian Geographic, but his friend and CEO Ike Bain persuaded him to change his mind and soon it was a successful business. He sold the business to Fairfax Media in 1995 for A$41 million.[18]

Film production[edit]

Smith co-produced the documentary First Contact, in 1983, recounting the discovery, in 1930, of a flourishing native population in the interior highlands of New Guinea. The film went on to win Best Feature Documentary at the 1983 Australian Film Institute Awards[19] and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.[20]

Australian products[edit]

Smith founded Dick Smith Foods in 1999, a response to foreign ownership of Australian food producers, particularly Arnott's Biscuits, which in 1997 became a wholly owned subsidiary of the Campbell Soup Company. Dick Smith Foods only sold foods produced in Australia by Australian-owned companies and all profits went to charity.[21]

In 2018, Smith announced closure of the business in 2019, having distributed over A$10 million in profits to charity, citing aggressive competition from German-owned Aldi through a strategy including low-cost imports notwithstanding Aldi's claim to operate an Australian-first buying policy.[22]

Aviation regulation reformist[edit]

Smith has been an advocate for the civil aviation industry in Australia, having been appointed by Prime Minister Bob Hawke to be chairman of the board of the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) from February 1990 to February 1992. He also served as deputy-chairman and chairman of the board of the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA, the CAA's regulatory successor after the 1995 de-merger of the government's aviation operations including air traffic control) from 1997 until his resignation in 1999. During his CAA tenure, a comprehensive reform plan (including the Class G Demonstration airspace reform) was devised to improve safety,[23] streamline bureaucracy and reduce costs but, facing opposition from the incumbent commercial operators, particularly Qantas and Ansett, it was never implemented. Smith claimed this was because there was resistance to increased competition in the market. Smith faced the same obstacles as head of CASA and left, concluding that his work there had failed.[24]

Smith has campaigned ever since for the reining in of over-regulation of the industry, particularly of flight training operators where layers of compliance costs associated with instructor status, approvals to carry out training and aircraft airworthiness have been blamed for ultimately crippling the Australian aviation industry.[25] In October 2015, he recommended a mass exit from the industry: "I absolutely recommend that people get out of aviation as quickly as they can, sell up their businesses and close down".[26]

Aviation and adventures[edit]

Having developed a taste for outdoor adventures in the Scouts, Smith trained to acquired a pilot licence and went on to establish several long-distance flight records.

Smith's first significant adventure was in 1964 when he sailed with a group of Rover Scouts to Ball's Pyramid in the Pacific Ocean. Failing to top it on this occasion, Smith returned in 1980, completed an ascent and, together with Hugh Ward and John Worrall, formally claimed the land for Australia by unfurling the New South Wales state flag.[12]: 173 He went on, in 1988, to sue the state government over its ban on recreational climbing of the spire. His action was taken when the government refused an application by Greg Mortimer, the first Australian to climb Mt Everest, to make the climb.[27]

Smith learned to fly in 1972, graduating to a twin engine Beech Baron. In 1976, he competed in the Perth-to-Sydney air race.[28]

Smith conceived and initiated airline flights over Antarctica. His first flight was made by a chartered Qantas aircraft on 13 February 1977.[29] In August the same year, Smith chartered another jumbo, this time to take paying passengers on a 10-hour, 5,000 km flight over the Red Centre of the Outback in search of Lasseter's fabled but lost reef of gold.[30] The search, attended by Lasseter's son Bob and Aboriginal tracker and artist Nosepeg Tjunkata Tjupurrula, found nothing.[31]

At the age of 34, he purchased his first helicopter, a Bell Jetranger II, and, on 23 February 1979, obtained his licence to fly it.[12] In January 1980, with Rick Howell co-piloting the Jetranger, he made a record-setting flight from Sydney to Lord Howe Island and returned (1,163 km).[12]: 163

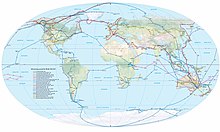

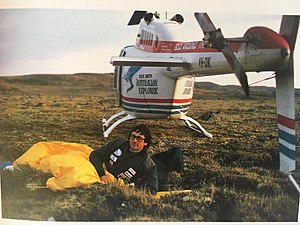

In 1982–83, Smith successfully completed the first solo helicopter flight around the world. His flight began in Fort Worth, Texas, on 5 August 1982, in a newly purchased Bell Jetranger 206B.[32][33]

For the next 20 years, Smith would come to hold several other world aviation records, made in rotary and fixed-wing aircraft and beneath balloons:

- First solo circumnavigation by helicopter (1983)[34]

- First helicopter to the North Pole (1987)[35]

- First circumnavigation landing at both poles (1989)[36][37]

- First non-stop balloon crossing of the Australian continent (1993)[38]

- First east-west circumnavigation by helicopter (1995)[39]

- First Trans-Tasman balloon flight (2001)[38]

On 19 August, the 50th anniversary of James Mollison's solo crossing of the Atlantic, Smith completed the first solo Atlantic crossing in a helicopter when he arrived at Balmoral Castle, United Kingdom to be greeted by a waiting (then prince) King Charles III.[40], then to London and Sydney, Australia, where he arrived on 3 October 1982, 23,092 km later. On 25 May 1983, the final stage of the flight started. Not being granted permission to land in the Soviet Union, he arranged to land on a ship to refuel. His journey ended on 22 July 1983, the 50th anniversary of Wiley Post's solo aeroplane flight around the world on 22 July 1933.[41]

Smith made the first helicopter flight to the North Pole, upon his third attempt in his Jetranger helicopter. In 1986, he had to give up 670 kilometres short of his destination because his navigation equipment was beginning to fail and visibility had dropped to almost zero. He failed once more, before his successful flight on 28 April 1987. The flight was made possible by having fuel delivered in a DHC-6 Twin Otter for refuelling in parts of the Arctic Circle.[42]

In 1988–89, Smith flew a Twin Otter aircraft VH-SHW, landing at both the North and South Poles,[36][43] making him the first person to complete such a circumnavigation.[44] The flight followed the "vertical" South-North-South track, (keeping broadly between 80 and 150 degrees E, heading south, and 60 and 100 degrees W, heading north) departing Sydney, Australia, on 1 November 1988, and returning on 28 May 1989.[45] The journey included the first flight made from Australia to the Australian Antarctic Territory.[46]

In August and again in October 1989, Smith, piloting his own helicopter, initiated and conducted searches in remote tracts of the Simpson Desert for the first stage of the Redstone Sparta rocket which had carried Australia's first satellite into orbit, making the nation only the fourth to succeed in doing so, on 29 November 1967. His search was ultimately successful, the relic recovered in an elaborate 22-person overland expedition the following year and placed on display in Woomera.[47]: 76–80

In October 1991, Smith was the second person to fly over Mount Everest.[48] Dick and Pip Smith circled the summit in his Cessna Citation, taking photographs.[49]

Smith and his co-pilot John Wallington made the first balloon trip across Australia, in a Cameron-R77 Rozière balloon, Australian Geographic Flyer,[50] on 18 June 1993,[51] for which he received the Commission Internationale d'Aerostation (FAI Ballooning Commission)'s 1995 Montgolfier Diploma.[52] In November of the same year, Smith broke the record for a purely solar-powered vehicular crossing of the Australian continent. Driving the Aurora Q1 for eight-and-a-half days, he completed the 2,530-mile (4,070 km) journey from Perth to Sydney at an average speed of 31 miles per hour (50 km/h). The vehicle was equipped with 1,943 solar cells epoxied to its fibreglass shell, with lead-acid and lithium-thionol batteries for storage, producing a maximum of 1.4 kW. He achieved a 20-day reduction in the record previously set by Hans Tholstrup and Larry Perkins 12 years earlier in The Quiet Achiever.[53][54]

In June 1995, Smith completed another helicopter flight around the world, this time with his wife Pip. He bought a twin-engine Sikorsky S-76. At their journey's end, Dick and Pip had completed the first east to west helicopter flight around the globe, flown more than 39,607 nautical miles (73,352 km).[49] The same year, he climbed the most remote of the seven summits, Carstensz Pyramid in Irian Jaya with Peter Hillary and Greg Mortimer.[12]: 197

On 7 January 2006, Smith flew his Cessna Grand Caravan from Sydney to Hari Hari on the West Coast of New Zealand's South Island to mark the 75th anniversary of the first solo trans-Tasman flight by Guy Menzies in 1931.[55]

Stunts[edit]

Smith has also attempted a number of well-publicised practical jokes, including the April Fool's Day attempt to tow a purported iceberg from Antarctica into Sydney Harbour in 1978, a new source of fresh water.[56] In the 1970s, Smith appeared on a pogo stick on various television programs, including Channel 9's Chris Kirby Show, as a promotional gimmick.[citation needed] In the early 1980s, Dick Smith organised the humorous promotional stunt in which a London double-decker bus jumped 16 motorcycles,[57] an inversion of Evel Knievel's 1979 motorcycle jump over buses during an Australian visit.[58] The bus was driven by adventurer Hans Tholstrup and Smith, who had been set up as its conductor, decided at the last minute to stay on board during the jump.[59][60]

Writing[edit]

Dick wrote several books about his trips and the challenge facing his country.

- Smith, Dick (1991). Our fantastic planet: Circling the globe via the poles with Dick Smith. Australian Geographic. ISBN 978-1862760073.

- Smith, Dick (1992). Solo around the world. Australian Geographic. ISBN 9781862760080.

- Smith, Dick; Smith, Pip; Inder, Stuart (1996). Above the World: A Pictorial Circumnavigation. Australian Geographic. ISBN 9781862760172.

- Smith, Dick (2011). Dick Smith's Population Crisis: The Dangers of Unsustainable Growth for Australia. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1742376578.

- Smith, Dick (2015). Balls Pyramid: Climbing the World's Tallest Sea Stack. Self-published. ISBN 978-0646946030.

Philanthropy[edit]

Beginning with his first charter in February 1977, Smith's Antarctic flights (operated by Qantas) had raised A$70,000 for charities including the Muscular Dystrophy Association, Foundation for National Parks & Wildlife (then of New South Wales) and Australian Museum over the following year.[61]

In the 1980s, Smith gave millions to Life Education Centres which taught schoolchildren about the health effects of smoking, alcohol, and narcotics. In 1988, he published and distributed over 100,000 copies of Truth an Ad magazine delivering that message, and ran anti-tobacco industry ads in newspapers.[57] In 1985, Smith conceived, organised and led the first of what was to become a major annual motoring event, the B to B Bash, the proceeds of which go to Variety, the Children's Charity. Smith's Bourke to Burketown route through remote areas of the Outback raised A$250,000 while a total of over A$200 million has been raised for the charity by the event in the past 30 years.[62]

In 1987, Smith established the Australian Geographic Society Adventure Awards and is patron of the society.[63] As its chairman, he initiated and led the restoration of polar adventurer Sir Hubert Wilkins' childhood home near Mt Bryan, South Australia, a nine-year project completed in 2001.[64]

Smith became a major philanthropist after the sale of his electronics business, contributing A$1 million yearly,[65][66][67] including the Salvation Army,[68] the Australian Lions Foundation,[69] Rotary Australia World Community Service,[70] Country Women's Association,[71] The Scout Association of Australia, Wild Care Inc. of Tasmania and the Australian Indigenous Education Foundation.[72] The construction of an orphanage and library at Onaba, in the Panjshir Valley, Afghanistan, was substantially funded by Smith.[73]

In October 2017, Smith made a A$250,000 donation to the Namatjira Legacy Trust as part of a settlement negotiated by him for transfer from commercial interests of all copyright in the works of Albert Namatjira, to the benefit of Namatjira's descendants and the Aboriginal community at large.[74][75]

Smith has been consistently openly critical of tax evasion by the wealthy and their failure to be active in philanthropy, cajoling billionaires Rupert Murdoch[76] and Harry Triguboff[77] to do more.[78]

Involvement in public affairs[edit]

In addition to his two terms of office heading the Australian Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) and Civil Aviation Safety Authority in the 1990s, Smith has engaged in a diverse range of civic activities.

Smith is a founder and a patron of the Australian Skeptics. In July 1980, Smith collaborated with renowned sceptic James Randi to test water divining, offering a prize of A$40,000 for a successful demonstration.[79]

Within days of Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating's 1995 parliamentary announcement of his intention to make Australia a republic by 2001,[80] public opinion was found to favour Smith as the nation's first president.[81]

Then Prime Minister John Howard appointed Smith founding chairman of the National Council for the Centenary of Federation in December 1996 and he served till February 2000.[82]

In early 2005, Dick Smith gave public support to the longest-detained asylum seeker, Peter Qasim, including offering to visit India to find evidence to support Qasim's claims.[83] Qasim was later released on the night of 16 July 2005, after 6 years and 10 months in detention, as a result of Immigration Minister Amanda Vanstone giving him a temporary visa, allowing him to live in the community and receive welfare, but allowing the government to deport him if and when another country will accept him.[84]

In response to a large increase in pertussis cases during a 2008–09 outbreak,[85] Smith funded a national ad in The Australian encouraging parents to "Get The Facts" and derided the Australian Vaccination Network as an anti-vaccination organisation.[86]

In November 2009, he paid a large share of the ransom to free Australian photojournalist Nigel Brennan and Canadian journalist Amanda Lindhout who were both being held hostage in Somalia.[87]

In February 2012, Smith expressed himself skeptical of the purported Energy Catalyzer cold fusion device. On 14 February, he offered the inventor Andrea Rossi US$1 million if he were to repeat the demonstration of 29 March of the year before, this time allowing particular care to be given to a check of the electric wiring of the device, and to the power output. The offer was declined by Rossi before the lapse of 20 February acceptance deadline that had been set by Smith.[88] Smith subsequently offered US$1 million "to any person or organisation that can come up with a practical device that has an output of at least one kilowatt of useful energy through LENRs (low energy nuclear reactions)." The offer remained open, unclaimed, until January 2013.[89]

Political activism and conservation[edit]

In 1989, Smith offered an A$25,000 reward for discovery, dead or alive, of the elusive Australian night parrot. A dead specimen was found the next year by three ornithologists, associated with the Australian Museum, who claimed the prize and efforts to find living specimens were sparked. Eventually, in 2013, the first confirmed sighting in over a century was confirmed.[90]

Smith donated A$60,000 in February 2007 towards a campaign to secure a fair trial for then Australian terrorism suspect David Hicks who had been held in a U.S. military prison in Cuba's Guantanamo Bay detention camp for five years.[91] Smith said he wanted Hicks to get "a fair trial, a fair go".[91] Fresh charges, including attempted murder, had been filed against Hicks earlier that month.[92] Hicks pleaded guilty to a lesser charge in March 2007 as part of a plea bargain,[93] and was released from custody in December 2007.[94]

Smith, together with two others, offered to financially assist Australian Greens leader Bob Brown to satisfy a A$240,000 costs order after Brown lost an anti-logging case he brought against Forestry Tasmania.[95] A failure to pay would have resulted in Brown having to declare bankruptcy, and therefore lose his seat in the Senate.[96]

In 2011, Dick Smith expressed support for action on climate change, including the introduction of a carbon tax, and criticized the response to actress Cate Blanchett speaking out on the matter.[97] In 2013, Smith released a documentary, Ten Bucks a Litre, profiling Australia's current energy sources and future options.[98][99] Smith explained his positive position on nuclear power generation in a 21 July 2017 interview with former Labor Party leader Mark Latham, citing France as having been particularly successful.[100]

In December 2011, Smith was appointed as a consulting professor in the Department of Biology, School of Humanities and Sciences of Stanford University, California, by Dean Richard P. Saller,[101] in recognition of his work in relation to environmental issues.

A newly identified 20-million-year-old koala relative was named Litokoala dicksmithi in honour of Smith in May 2023. Lead author of the research paper, Karen Black, explained she chose to recognise Smith "for his long-term financial support of Australian scientific endeavour and in particular fossil research at Riversleigh."[102]

Aboriginal reconciliation[edit]

As chairman of the National Centenary of Federation Council (1996–2000), Smith advocated renaming 26 January, Australia Day (which commemorates the arrival of the first fleet of British settlers in 1788), as "First Fleet Day" in recognition of the fact it was not a day for celebration by all Australians.[103]

On 29 June 1998, Smith was one of the original Ambassadors for Reconciliation announced by the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation, to promote reconciliation as a broad people's movement.[104][105]

On 10 October 2023, Smith was one of 25 Australians of the Year who signed an open letter supporting the Yes vote in the Indigenous Voice referendum.[106][107]

Population policy activism[edit]

In August 2010, Smith announced he would be devoting himself to questions of global population, overpopulation, and alternatives to an endless economic growth economy. He produced and appeared in the feature-length documentary Dick Smith's Population Puzzle.[108] In the documentary, Smith called the campaign the most important thing he had ever done in his life.[109]

On 6 December 2016, Smith spoke in support of the One Nation party's policy of reducing immigration to historical levels of about 70,000 per annum whilst at the same time rejecting its leader Pauline Hanson's call for a Muslim ban. Smith described himself as pro-immigration but cautioned that the very high rates of immigration would increase population beyond carrying capacity.[110][111][112]

In September 2017, Smith joined the Sustainable Australia party.[113]

The Dick Smith Party[edit]

In March 2015, Dick Smith registered The Dick Smith Party, but would not be running as a candidate himself. The party stated it intended to focus on the Senate and would run on a platform of curbing unnecessary regulation and population growth.[114] Smith is opposed to Australia's large rates of immigration on grounds of environmental sustainability.[115]

Dick Smith Fair Go[edit]

On 15 August 2017, Smith launched his "Fair Go" campaign to pressure Australia's major political parties to incorporate population policy into their platforms and to radically increase taxation on the rich and corporates,[116] pledging to spend another A$2 million on promoting population policy at the next Federal election if no major party would commit to reducing immigration to 70,000 per annum from a level then averaging in excess of 200,000.[117][118][119] The campaign became permanent as the Dick Smith Fair Go Group which also agitates for economic reforms to tackle income inequality and a return to affordable housing.[120]

Awards and honours[edit]

I began as a Cub at eight and went right through to Rovers at age 23. I was very much a loner and Scouting gave me mateship, taught me organisation and how to motivate people. That's why I was able to be the success I am.

— Dick Smith[121]

| Year | Awards and distinctions received by Dick Smith |

|---|---|

| 1966 | Baden-Powell Award, Scouts Australia[121] |

| 1983 | Sword of Honour, Honourable Company of Air Pilots[122] |

| 1983 | Oswald Watt Gold Medal, Royal Federation of Aero Clubs of Australia[123] |

| 1986 | Australian of the Year, National Australia Day Council[124][125][126] |

| 1990 | Hartnett Medal, Royal Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce. Awarded by Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.[127] |

| 1992 | Fellow, Royal Society of Arts[128] |

| 1992 | Lindbergh award, Lindbergh Foundation[129] |

| 1997 | Australian Living Treasure, National Trust of Australia[130] |

| 1999 | Officer of the Order of Australia[131] |

| 2000 | Adventurer of the Year, Australian Geographic Society[132][133] |

| 2001 | Centenary Medal, Australian Government[134] |

| 2006 | 100 Most Influential Australians, The Bulletin magazine[135] |

| 2008 | Lowell Thomas Award, The Explorers Club[136][137] |

| 2013 | Inducted into the Australian Aviation Hall of Fame[138] |

| 2014 | 50 years of adventure Award, Australian Geographic Society[139] |

| 2015 | Companion of the Order of Order of Australia[140] |

References[edit]

- ^ a b Smith, Dick (30 May 2011), "The idiocy of endless growth", The Age, Melbourne, retrieved 6 March 2011

- ^ Num, Cora (1999). A line of Smiths. The Ancestors of Dick Smith. Australia: Self-published. p. 90.

- ^ "Queen's birthday honours". Sydney Morning Herald. 8 June 2015.

- ^ "Dick Smith Receives High Award in Australia". Skeptical Inquirer. 40 (1): 9.

- ^ a b "Sunday Profile, Dick Smith". ABC. 17 July 2005. Archived from the original on 13 September 2005. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ Gallery of NSW Dick Smith on his grandfather, the photographer Harold Cazneaux's channel on YouTube

- ^ Rolfe, Brooke (20 March 2023). "Entrepreneur Dick Smith reveals extent of his academic failings". News.com.au. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ a b c Feneley, Rick (8 June 2015). "Queen's Birthday honours: Dick Smith, a 'dumb' kid who was almost never famous". Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, Australia. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ "Dick Smith". www.scouts.com.au. Scouts Australia. Archived from the original on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

I owe a lot to Scouting. It had to be the most fantastic influence on my life. It taught me responsible risk-taking.

- ^ Parker, Peter (2019). Australian Ham Radio Handbook : everything you need to succeed in amateur radio. [Melbourne]. ISBN 9781688856639.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "VK2DIK". QRZ.COM. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith, Dick (June 2015). Balls Pyramid, Climbing the World's Tallest Sea Stack. Dick Smith Adventure P/L. ISBN 978-0-646-94603-0.

- ^ "Car Stereo According to St Dick". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, Australia. 3 August 1969. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ Bain, Ike (2002). The Dick Smith Way. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0074711606.

- ^ "Profile: Dick Smith". 13 September 2007.

- ^ Dagge, John (17 February 2015). "Pacific Brands suffers big loss and Fortescue earnings tumble as ANZ profit machine rolls on". Herald Sun. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ Low, Catie (31 March 2016). "Receiver finally calls time on Dick Smith stores". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, Australia: Fairfax Media. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ Dalton, Trent (19 May 2018). "The World According to Dick". The Weekend Australian Magazine. p. 17.

- ^ AACTA. "Past Winners: 1983 Winners & Nominees". Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ "First Contact". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2010. Archived from the original on 14 May 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^ "Dick Smith Foods – Mission Statement". About Us. Dick Smith Foods. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- ^ O'Malley, Nick (26 July 2018). "Dick Smith to close his grocery line, blaming unbeatable Aldi". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ^ Smith, Dick. "Unsafe skies" (PDF). foreword by Max Hazelton

- ^ "Aviation reform could have saved Ansett". Crikey. 16 September 2001. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ Ingall, Jennifer (11 May 2016). "Claims that flying regulations are crippling general aviation industry". ABC News. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ Dick Smith recommends mass industry exit Archived 20 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine Pro Aviation. Retrieved 15 November 2015

- ^ Bailey, Paul (28 July 1988). "Dick Smith in court for adventure". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Glines, Carroll V. (2002). Round-the-World Flights. Potomac Books, Incorporated. p. 316. ISBN 978-1-57488-448-7.

- ^ Haward, Marcus G (2011). Australia and the Antarctic Treaty System: 50 years of influence. UNSW Press. p. 318. ISBN 978-1-74224-098-5.

- ^ "They'll Race in Outback Stakes – by Camel". Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, New South Wales: Fairfax. 21 August 1977. p. 13.

- ^ Mason, Frank (1978). "Striking Out". South African Lapidary Magazine. 12 (2): 87.

- ^ Powerhouse Museum. "Bell 206B Jetranger III helicopter flown by Dick Smith, 1982. Statement of significance". Powerhouse Museum. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

The Bell Jetranger III helicopter, Dick Smith Australian Explorer, was flown by Australian businessman and adventurer Dick Smith on the first solo circumnavigation of the world in a rotary wing aircraft in 1982/3.

- ^ "Bell Jetranger helicopter flown around the world by Dick Smith". Powerhouse Collection. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ "40th Anniversary of the World's First Solo Circumnavigation by Helicopter by Dick Smith". Flightline Weekly. 9 August 2023. Archived from the original on 21 January 2024. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ "Smith's Copter over N Pole". Canberra Times. 30 April 1987.

- ^ a b Robert Gott (1998). "10: Further adventures" (pdf). Makers & Shakers. Heinemann Library. pp. 38–41. ISBN 978-1-86391-878-7. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ "The Dome is Home--South Pole history 1975-90". Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ a b "Richard 'Dick' Smith AC". Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Gott, Robert (1998). Makers & Shakers, Heinemann Library. p. 46. ISBN 1-86391-878-7.

- ^ Baker, Rebecca (7 November 2013). "On this day: Dick Smith's around-the-world solo flight". Australian Geographic. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ Smith, Dick. The Earth Beneath Me, Angus & Robertson Publishers (1983). ISBN 0-207-14630-6

- ^ Robert Gott. Makers & Shakers, Heinemann Library, 1998. p. 38 ISBN 1-86391-878-7

- ^ "The Dome is Home--South Pole history 1975-90". Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ "A Magic Carpet Ride over the Poles with Dick Smith". Sydney Morning Herald. 14 November 1991. p. 5. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ Smith, Dick (1991). Our Fantastic Planet; Circling the Globe via the Poles with Dick Smith. Australian Geographic.

- ^ Kriwoken R, Lorne K; Williamson, John W (1993). "Hobart, Tasmania: Antarctic and Southern Ocean connections" (PDF). Polar Record. 29 (169): 93. Bibcode:1993PoRec..29...93K. doi:10.1017/S0032247400023548. S2CID 130722655.

- ^ Douherty, Kevin. "Retrieving Woomera's Heritage" (PDF). Artefactsconsortium.org. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ^ Bruce, David (22 October 1991). "Dick Smith Over The Top". The Age. Archived from the original on 30 December 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

Note:As posted on balloonflight.com.au

- ^ a b Robert Gott. Makers & Shakers, Heinemann Library, 1998. p. 46 ISBN 1-86391-878-7

- ^ Cawsey, Richard. "Roziere Balloons". Bison Consultants Ltd. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "Crossing of Australia by hot air balloon". Australian Geographic. 18 June 2014.

- ^ "Awards". Australian Ballooning Federation. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ Aldrich, Bob (1995). ABC's of Afv's: A Guide to Alternative Fuel Vehicles. Diane Publishing. ISBN 9780788145933.

- ^ Smith, Pip (July–September 1995). "Aurora's Place in the Sun" (PDF). Australian Geographic. p. 78.

- ^ Madgwick, Paul (1 August 2006). "Dick Smith recreates first solo trans-Tasman flight". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 18 April 2006.

- ^ "The Sydney Iceberg". museumofhoaxes.com. 23 January 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ^ a b Clark Scott, David (18 August 1988). "Aussie aims to snuff out cigarette ads". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ "Evel Knievel". Stevemandich.com. 13 February 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "The Flying Omnibus". Motorcycle Gallery. Dropbears. 25 March 2006. Archived from the original on 16 January 2000. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- ^ "Front Seat of the Race Bus". Millennium Ride. 11 November 2002. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- ^ Rowley, David (24 October 1978). "Charities Cashing in on Jumbo Joy Flights". Mirror.

- ^ "2017 Variety Bash takes shape". Motoring. carsales.com. 25 February 2017. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ "Australian Geographic Society awards adventure and conservation". Sustainability Matters. 28 October 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ "Coming Home, Memorial to Sir Hubert Wilkins" (PDF). Australian Geographic. October–December 2001.

- ^ "Profile: Dick Smith". Sydney Morning Herald. 13 September 2007. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ "The World According to Dick". The Weekend Australian. 19–20 May 2019. p. 17.

- ^ Caneva, Lena (19 August 2014). "Dick Smith distributes part of $1M to charity". Probono Australia.

- ^ "Spike in homelessness: Salvos". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. 29 June 2010. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^ Johnson, Greg (28 April 2013). "Smith makes $1 million donation". Fundraising & Philanthropy Australia. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ Conway, Doug (7 December 2016). "From politics to philanthropy as Dick Smith donates $1m to Rotary". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ Pedersen, Daniel (15 June 2018). "Dick Smith's million-dollar gift for the Country Women's Association". The Courier. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ^ "Dick Smith donates proceeds of Citation sale". Australian Aviation. 8 December 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ "Dick Smith Shelter, Panjshir Valley, Afghanistan". Make a Mark Australia. 3 April 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ Neill, Rosemary (14 October 2017). "A Whole New Landscape Opens Up to Celebrate Namatjira". The Weekend Australian.

- ^ Dayman, Isabel (15 October 2017). "Albert Namatjira's family regains copyright of his artwork after Dick Smith intervenes". ABC News. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ Heanue, Siobhan (27 April 2013). "Dick Smith takes aim at Murdoch's philanthropy record". Radio Australia. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ Benns, Matthew (17 December 2017). "Millionaire Dick Smith calls on billionaire Harry Triguboff to donate more of his money to charity". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ Piotrowski, Alison (19 December 2017). "Dick Smith vs Harry Triguboff in battle of the billions". 9news. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ James Randi (28 July 2009). "Australian Skeptics Divining Test". Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ "Keating: An Australian Republic – The Way Forward". Australian Politics. 8 June 1995. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ "President Smith: Adventurer the people's choice". The Sun-Herald. 11 June 1995. p. 1.

- ^ "Archbishop Hollingworth to Chair the National Council for the Centenary of Federation". Australian Government, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 18 February 2000. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ "Dick Smith flies to Baxter detainee's aid". ABC News Online. 1 March 2005. Archived from the original on 7 May 2009. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

- ^ Bockmann, Michelle Wiese (18 July 2005). "Free after 7 years, detainee wants job". The Australian. News Ltd. MATP. p. 5. AUS_T-20050718-1-005-732911. Retrieved 15 February 2024 – via Dow Jones Factiva.

- ^ "Pertussis in Australia". Center for Disease Control. 17 April 2009. Archived from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ^ Hall, Louise (16 August 2009), "Vaccine fear campaign investigated", The Sydney Morning Herald, retrieved 16 August 2009

- ^ "Dick Smith contributed to Aussie hostage's ransom". Fairfax Media. 27 November 2009. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ E-Cat Proof Challenge: $1,000,000 is a "Clownerie"? (Updated), Forbes, February 2012, downloaded 19 February 2012

- ^ US $1 Million Reward for First Successful One Kilowatt or More LENR Demonstration Archived 2 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved 3 July 2012

- ^ Slezak, Michael. "Australian night parrot legend lives on but bird remains as elusive as ever". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Dick Smith donates $60,000 to free Hicks". NineMSN. 18 February 2007. Archived from the original on 8 May 2009. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

- ^ Alexander Downer; Philip Ruddock (3 February 2007). "Joint Media Release – Minister for Foreign Affairs and Attorney General: David Hicks: charges outlined". Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Australian Government Attorney-General's Department. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

- ^ Scott Horton (2 April 2007). "The Plea Bargain of David Hicks". Harper's Magazine. The Harper's Magazine Foundation. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

- ^ Rory Callinan (29 December 2007). "Aussie Taliban Goes Free". Time. Time Inc. Archived from the original on 1 January 2008. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

- ^ Peter Wels (10 June 2009). "I took advice on court costs, says Bob Brown". The Examiner (Tasmania). Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ "Dick Smith to bail Brown out". ABC News. 9 June 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ "I was gutless over climate ads: Dick Smith". Sydney Morning Herlad. 30 May 2011.

- ^ "Ten Bucks a Litre, 2013". Screen Australia. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ Matt Campbell (1 August 2013). "Dick Smith gazes into his automotive crystal ball". drive.com.au.

- ^ "Dick Smith rips population ponzi on Mark Latham's Outsiders". MacroBusiness. 20 July 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "Consulting Professor in the Center for Conservation Biology Archived 16 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine". Stanford University. Retrieved 4 February 2011

- ^ Black, Karen H.; Julien Louys; Gilbert J. Price (14 May 2013). "Understanding morphological variation in the extant koala as a framework for identification of species boundaries in extinct koalas (Phascolarctidae; Marsupialia)" (PDF). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 12 (2): 237–264. doi:10.1080/14772019.2013.768304. ISSN 1478-0941. S2CID 46906299.

- ^ "The truth is January 26 should be First Fleet Day, not Australia Day". The Sydney Morning Herald. 25 January 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ "Prominent Australians to Launch Ambassadors for Reconciliation Project". classic.austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ "Appendix 7—List of ambassadors for reconciliation". classic.austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ Butler, Josh (11 October 2023). "Australian of the Year winners sign open letter saying no vote in voice referendum would be a 'shameful dead end'". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ^ Winter, Velvet (10 October 2023). "Voice referendum live updates: Australians of the Year Yes vote letter in full". ABC News (Australia). Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ^ Simon Nasht (12 August 2010). "Dick Smith's Population Puzzle". Australia: ABC1 (ABC.net.au). Retrieved 8 June 2014. (Download Transcript-PDF-511Kb)

- ^ Guy Pearse (June 2011). "Dick Smith's Population Crisis". The Monthly.

- ^ Sharaz, David (6 December 2016). "Dick Smith drawn to help Hanson over immigration control rhetoric". SBS News. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "Dick Smith backs Pauline Hanson on immigration". The Guardian. Australian Associated Press. 6 December 2016.

- ^ "Dick Smith backs Pauline Hanson's One Nation state and federal election plans".

- ^ "Dick Smith joins lower immigration party". SBS. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ Rose, Danny (26 March 2015). "Dick Smith won't stand for own party". The West Australian. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ Stiles, Jackson. Launch of Political Party The New Daily. Retrieved 6 May 2015

- ^ "'Angry' Dick Smith 'forced' to spend $1m on new Grim Reaper TV ad". AdNews. 14 August 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ Chung, Frank (15 August 2017). "'They'll bring out the pitchforks and revolt': Dick Smith launches $1 million anti-immigration ad". news.com.au. Australia: News Limited. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ Benns, Matthew (13 August 2017). "Dick Smith launches $1 million TV ad campaign to slash immigration, increase taxes for super rich". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ "Dick Smith again calls for immigration cuts in new campaign". SBS News. SBS. 15 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ Williams, Stephen (December 2017). "Smith Shows Aussie Might" (PDF). Sustainable Population Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Dick Smith". Famous Scouts. Scouts Australia. Archived from the original on 18 September 2007. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- ^ "The Sword of Honour". Honourable Company of Air Pilots.

- ^ "Oswald Watt Gold Medal Awards" (PDF). Royal Federation of Aero Clubs of Australia.

- ^ "National Australia Day Council – Australian of the Year Award". Award Recipients, Australian of the Year. National Australia Day Council. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- ^ Lewis, Wendy (2010). Australians of The Year 1960 – 2010. Pier 9 Press. ISBN 978-1-74196-809-5.

- ^ 1960–2010 Australians of the Year, Murdoch Books Australia, ISBN 978-1-74196-809-5

- ^ "Dick Smith's RSA Hartnett Medal". Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ "Dick Smith Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts". Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ "The Lindbergh Award". Lindbergh Foundation. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ "Australian Living Treasure". Award Recipients. National Trust of Australia (NSW). Archived from the original on 2 November 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- ^ "Mr Richard Harold (Dick) Smith". Australian Government - Office of the Prime Minister and cabinet. Archived from the original on 11 October 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ "Dick Smith, Australian, Electronics, Retail & Aviation Magnate". AussieTycoon. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ^ "AG Society Adventure Awards". Australian Geographic. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ^ "Australian Honours Search". Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Australian Government. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ "The 100 most influential Australians". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfaix Media. 27 June 2006. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ "Dick Smith". ANZEC. Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ "The Lowell Thomas Award". The Explorers Club. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ "Richard Harold (Dick) Simth AC". Australian Aviation Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 18 November 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ "Australian Geographic Society 2014 Special Award". Australian Geographic. 27 October 2014. Archived from the original on 11 October 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ "Companion (AC) in the General Division of the Order of Australia" (PDF). Governor General of the Commonwealth of Australia. The Australian Honours Secretariat. 8 June 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

For eminent service to the community as a benefactor of a range of not-for-profit and conservation organisations, through support for major fundraising initiatives for humanitarian and social welfare programs, to medical research and the visual arts, and to aviation.

Further reading[edit]

- Davis, Pedr. Kookaburra: The Most Compelling Story in Australia's Aviation History, Lansdowne books, Dee Why, 1980, ISBN 0-7018-1357-1

- Smith, Dick. The Earth Beneath Me: Dick Smith's Epic Journey Across the World, Angus & Robertson London 1983, ISBN 0-207-14630-6

- Smith, Dick. Our Fantastic Planet: Circling the Globe Via the Poles With Dick Smith, Terry Hills N.S.W. Australian Geographic, 1991, ISBN 1-86276-007-1

- Smith, Dick. Solo Around the World, Australian Geographic, Terrey Hills, 1992, ISBN 1-86276-008-X

- Gott, Robert. Makers and Shakers, Reed Educational & Professional Publishing, Melbourne, 1998, ISBN 1-86391-878-7

- Smith, Dick and Pip. Above the World: A Pictorial Circumnavigation, Australian Geographic, Terrey Hills, 1996, ISBN 1-86276-017-9

- Bain, Ike. The Dick Smith Way, McGraw-Hill, Sydney, 2002, ISBN 0-07-471160-1

- Smith, Dick. Dick Smith's Population Crisis: The Dangers of Unsustainable Growth of Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2011 ISBN 978-1-74237-657-8

- Monica Attard (17 July 2005). "Sunday Profile interview with Dick Smith". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Smith, Dick (June 2015). Balls Pyramid, Climbing the World's Tallest Sea Stack. Dick Smith Adventure P/L. ISBN 978-0-646-94603-0.

- Smith, Dick (November 2021). "My Adventurous Life". Allen & Unwin ISBN 978-1-76087-889-4. (Australian Book Industry Awards "2022 Biography Book of the Year").

External links[edit]

- 1944 births

- Australian autobiographers

- Australian businesspeople in retailing

- Living people

- People from the North Shore, Sydney

- Amateur radio people

- Companions of the Order of Australia

- Australian of the Year Award winners

- Australian philanthropists

- Australian company founders

- Australian film studio executives

- Businesspeople from Sydney

- Rotorcraft flight record holders

- Balloon flight record holders

- Australian aviation record holders

- Australian Geographic people

- Australian sceptics

- Australian republicans

- Australian balloonists

- Helicopter pilots

- People educated at North Sydney Technical High School