Chagos Archipelago sovereignty dispute

Sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago is disputed between Mauritius and the United Kingdom. Mauritius has repeatedly stated that the Chagos Archipelago is part of its territory and that the United Kingdom claim is a violation of United Nations resolutions banning the dismemberment of colonial territories before independence. On 22 May 2019, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a non-binding resolution declaring that the archipelago was part of Mauritius, with 116 countries voted in favor of Mauritius while six opposed it.

The UK government has declared that it has "no doubt" about its sovereignty over the Chagos, yet has also said that the Chagos will be returned to Mauritius once the islands are no longer required for military purposes. Given the absence of any meaningful progress with the UK, Mauritius took up the matter at various legal and political forums.

On 3 November 2022, it was announced that the UK and Mauritius had decided to begin negotiations on sovereignty over the British Indian Ocean Territory, taking into account the recent international legal proceedings.[1] In December 2023, it was reported that the UK government was planning to discontinue the talks.[2]

History[edit]

The Constitution of Mauritius states that the Outer islands of Mauritius includes the islands of Mauritius, Rodrigues, Agaléga, Cargados Carajos and the Chagos Archipelago, including Diego Garcia and any other island comprised in the State of Mauritius. The Government of the Republic of Mauritius has stated that it does not recognise the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) which the United Kingdom created by excising the Chagos Archipelago from the territory of Mauritius prior to its independence, and claims that the Chagos Archipelago including Diego Garcia forms an integral part of the territory of Mauritius under both Mauritian law and international law.[3]

In 1965, the United Kingdom split the Chagos Archipelago away from Mauritius with the agreement of the Mauritian government, and the islands of Aldabra, Farquhar, and Desroches from the Seychelles, to form the British Indian Ocean Territory. The islands were formally established as an overseas territory of the United Kingdom on 8 November 1965. However, with effect from 23 June 1976, Aldabra, Farquhar, and Desroches were returned to the Seychelles on their attaining independence.

In 2012, the African Union and the Non-Aligned Movement have expressed unanimous support for Mauritius.[4][better source needed] On 18 March 2015, the Permanent Court of Arbitration unanimously held that the marine protected area (MPA) which the United Kingdom declared around the Chagos Archipelago in April 2010 was created in violation of international law. The Prime Minister of Mauritius has stated that this is the first time that the country's conduct with regard to the Chagos Archipelago has been considered and condemned by any international court or tribunal. He described the ruling as an important milestone in the relentless struggle, at the political, diplomatic, and other levels, of successive Governments over the years for the effective exercise by Mauritius of the sovereignty it claims over the Chagos Archipelago. The tribunal considered in detail the undertakings given by the United Kingdom to the Mauritian Ministers at the Lancaster House talks in September 1965. The UK had argued that those undertakings were not binding and had no status in international law. The Tribunal firmly rejected that argument, holding that those undertakings became a binding international agreement upon the independence of Mauritius, and have bound the UK ever since. It found that the UK's commitments towards Mauritius in relation to fishing rights and oil and mineral rights in the Chagos Archipelago are legally binding.[5]

On 22 June 2017, by a margin of 94 to 15 countries, the UN General Assembly asked the International Court of Justice ("ICJ") to give an advisory opinion on the separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius before the country's independence in the 1960s. In September 2018, the International Court of Justice began hearings on the case. 17 countries argued in favour of Mauritius.[6][7] The UK apologised for the "shameful" way islanders were evicted from the Chagos Archipelago but were insistent that Mauritius was wrong to bring the dispute over sovereignty of the strategic atoll group to the United Nations’ highest court and continues to refuse to allow them to return.[8] The UK and its allies argued that this matter should not be decided by the court but should be resolved through bilateral negotiations, while bilateral discussions with Mauritius have been unfruitful over the past 50 years. On 25 February 2019, the judges of the International Court of Justice by thirteen votes to one stated that the United Kingdom is under an obligation to bring to an end its administration of the Chagos Archipelago as rapidly as possible. Only the American judge, Joan Donoghue, voted in favour of the UK. The president of the court, Abdulqawi Ahmed Yusuf, said the detachment of the Chagos Archipelago in 1965 from Mauritius had not been based on a "free and genuine expression of the people concerned." "This continued administration constitutes a wrongful act," he said, adding "The UK has an obligation to bring to an end its administration of the Chagos Archipelago as rapidly as possible and that all member states must co-operate with the United Nations to complete the decolonization of Mauritius."[9]

On 22 May 2019, the United Nations General Assembly debated and adopted a resolution that affirmed that the Chagos Archipelago, which has been occupied by the UK for more than 50 years, "forms an integral part of the territory of Mauritius". The resolution gives effect to an advisory opinion of the ICJ, demanded that the UK "withdraw its colonial administration ... unconditionally within a period of no more than six months". 116 states voted in favour of the resolution, 55 abstained and only Australia, Hungary, Israel and Maldives supported the UK and US. During the debate, the Mauritian Prime Minister described the expulsion of Chagossians as "a crime against humanity".[10] While the resolution is not legally binding, it carries significant political weight since the ruling came from the UN's highest court and the assembly vote reflects world opinion.[11] The resolution also has immediate practical consequences: the UN, its specialised agencies, and all other international organisations are now bound, as a matter of UN law, to support the decolonisation of Mauritius even if the UK continues to claim the area.[10]

The Maldives has a dispute with Mauritius with regards to the limit of its Exclusive Economic Zone (“EEZ”) and the EEZ of the Chagos Archipelago. In June 2019, Mauritius initiated arbitral proceedings against the Maldives at the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (“ITLOS”) to delimit its maritime boundary between the Maldives and the Chagos Archipelago. Among its preliminary objections, the Maldives argued that there was an unresolved sovereignty dispute between Mauritius and the UK over the Chagos Archipelago, which fell outside the scope of the ITLOS's jurisdiction. On 28 January 2021, the ITLOS concluded that the dispute between the UK and Mauritius had in fact already been determinatively resolved by the ICJ's earlier Advisory Opinion, and that there was therefore no bar to jurisdiction. The ITLOS rejected all five of the Maldives’ preliminary objections and found that Mauritius' claims are admissible.[12][13]

On 3 November 2022, the British Foreign Secretary James Cleverly announced that the UK and Mauritius had decided to begin negotiations on sovereignty over the British Indian Ocean Territory, taking into account the recent international legal proceedings. Both states had agreed to ensure the continued operation of the joint UK/US military base on Diego Garcia.[1][14] In December 2023, it was reported that the UK government was planning to discontinue the talks.[2]

Historical background[edit]

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (November 2022) |

Beginning in the late 15th century, Portuguese explorers began to venture into the Indian Ocean and recorded the location of Mauritius and the other Mascarene Islands, Rodrigues and Réunion (the latter presently a French overseas department). In the 16th century, the Portuguese were joined by Dutch and English sailors, both nations having established East India Companies to exploit the commercial opportunities of the Indian Ocean and the Far East. Although Mauritius was used as a stopping point in the long voyages to and from the Indian Ocean, no attempt was made to establish a permanent settlement.[15]

The first permanent colony in Mauritius was established by the Dutch East India Company in 1638. The Dutch maintained a small presence on Mauritius, with a brief interruption, until 1710 at which point the Dutch East India Company abandoned the island. Following the Dutch departure, the French government took possession of Mauritius in 1715, renaming it the Île de France.[15]

The Chagos Archipelago was known during this period, appearing on Portuguese charts as early as 1538, but remained largely untouched. France progressively claimed and surveyed the Archipelago in the mid-18th century and granted concessions for the establishment of coconut plantations, leading to permanent settlement. Throughout this period, France administered the Chagos Archipelago as a dependency of the Ile de France.[15]

In 1810, the British captured the Ile de France and renamed it Mauritius. By the Treaty of Paris of 30 May 1814, France ceded the Ile de France and all its dependencies (including the Chagos Archipelago) to the United Kingdom.[15]

The British Administration of Mauritius and the Chagos Archipelago[edit]

From the date of the cession by France until 8 November 1965, when the Chagos Archipelago was detached from the colony of Mauritius, the Archipelago was administered by the United Kingdom as a Dependency of Mauritius. During this period, the economy of the Chagos Archipelago was primarily driven by the coconut plantations and the export of copra (dried coconut flesh) for the production of oil, although other activities developed as the population of the Archipelago expanded. British administration over the Chagos Archipelago was exercised by various means, including by visits to the Chagos Archipelago made by Special Commissioners and Magistrates from Mauritius.[15]

Although the broad outlines of British Administration of the colony during this period are not in dispute, the Parties disagree as to the extent of economic activity in the Chagos Archipelago and its significance for Mauritius, and on the significance of the Archipelago's status as a dependency. Mauritius contends that there were "close economic, cultural and social links between Mauritius and the Chagos Archipelago" and that "the administration of the Chagos Archipelago as a constituent part of Mauritius continued without interruption throughout that period of British rule". The United Kingdom, in contrast, submits that the Chagos Archipelago was only "very loosely administered from Mauritius" and "in law and in fact quite distinct from the Island of Mauritius." The United Kingdom further contends that "the islands had no economic relevance to Mauritius, other than as a supplier of coconut oil" and that, in any event, economic, social and cultural ties between the Chagos Archipelago and Mauritius during this period are irrelevant to the Archipelago's legal status.[15]

The independence of Mauritius[edit]

Beginning in 1831, the administration of the British Governor of Mauritius was supplemented by the introduction of a Council of Government, originally composed of ex-officio members and members nominated by the Governor. The composition of this council was subsequently democratized through the progressive introduction of elected members. In 1947, the adoption of a new Constitution for Mauritius replaced the Council of Government with separate Legislative and Executive Councils. The Legislative Council was composed of the Governor as president, 19 elected members, 12 members nominated by the Governor and 3 ex-officio members.[15]

The first election of the Legislative Council took place in 1948, and the Mauritius Labour Party (the "MLP") secured 12 of the 19 seats available for elected members. The MLP strengthened its position in the 1953 election by securing 14 of the available seats, although the MLP lacked an overall majority in the Legislative Council because of the presence of a number of members appointed by the Governor.[15]

The 1953 election marked the beginning of Mauritius’ move towards independence. Following that election, Mauritian representatives began to press the British Government for universal suffrage, a ministerial system of government and greater elected representation in the Legislative Council. By 1959, the MLP-led government had openly adopted the goal of complete independence.[15]

Constitutional Conferences were held in 1955, 1958, 1961, and 1965, resulting in a new constitution in 1958 and the creation of the post of Chief Minister in 1961 (renamed as the Premier after 1963). In 1962 Seewoosagur Ramgoolam became the Chief Minister within a Council of Ministers chaired by the Governor and, following the 1963 election, formed an all-party coalition government to pursue negotiations with the British on independence.[15]

The final Constitutional Conference was held in London in September 1965 and was principally concerned with the debate between those Mauritian political leaders favouring independence and those preferring some form of continued association with the United Kingdom. On 24 September 1965, the responsible UK government minister, Anthony Greenwood, announced that the UK intended for Mauritius to become independent.[15] Mauritius became independent on 12 March 1968.[citation needed] Section 111 of the Constitution of Mauritius states that "Mauritius" includes[16] –

(a) the Islands of Mauritius, Rodrigues, Agaléga, Tromelin, Cargados Carajos and the Chagos Archipelago, including Diego Garcia and any other island comprised in the State of Mauritius;

(b) the territorial sea and the air space above the territorial sea and the islands specified in paragraph (a);

(c) the continental shelf; and

(d) such places or areas as may be designated by regulations made by the Prime Minister, rights over which are or may become exercisable by Mauritius.

Detachment of the Chagos Archipelago[edit]

This section contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (July 2017) |

During negotiations on granting Mauritian independence, the UK proposed to separate the Chagos Archipelago from the colony of Mauritius, with the UK retaining the Chagos under British control. According to Mauritius, the proposal stemmed from a UK decision in the early 1960s to "accommodate the United States’ desire to use certain islands in the Indian Ocean for defence purposes."[15]

The record before the Tribunal[which?] sets out a series of bilateral talks between the United Kingdom and the United States in 1964 at which the two States decided that, in order to execute the plans for a military facility in the Chagos Archipelago, the United Kingdom would "provide the land, and security of tenure, by detaching islands and placing them under direct U.K. administration."[15]

The suitability of Diego Garcia as the site of the planned military base was determined following a joint survey of the Chagos Archipelago and certain islands of the Seychelles in 1964. Following the survey, the United States sent its proposals to the United Kingdom, identifying Diego Garcia as its first preference as the site for the military facility. The United Kingdom and the United States conducted further negotiations between 1964 and 1965 regarding the desirability of "detachment of the entire Chagos Archipelago," as well as the islands of Aldabra, Farquhar and Desroches (then part of the Colony of the Seychelles). They further discussed the terms of compensation that would be required "to secure the acceptance of the proposals by the local Governments."[15]

On 19 July 1965, the Governor of Mauritius was instructed to communicate the proposal to detach the Chagos Archipelago to the Mauritius Council of Ministers and to report back on the council's reaction. The initial reaction of the Mauritian Ministers, conveyed by the Governor's report of 23 July 1965, was a request for more time to consider the proposal. The report also noted that Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam expressed "dislike of detachment". At the next meeting of the council on 30 July 1965, the Mauritian Ministers indicated that detachment would be "unacceptable to public opinion in Mauritius" and proposed the alternative of a long-term lease, coupled with safeguards for mineral rights and a preference for Mauritius if fishing or agricultural rights were ever granted. The Parties differ in their understanding of the strength of, and motivation for, the Mauritian reaction. In any event, on 13 August 1965, the Governor of Mauritius informed the Mauritian Ministers that the United States objected to the proposal of a lease.[15]

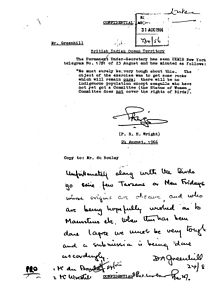

Discussions over the detachment of the Chagos Archipelago continued in a series of meetings between certain Mauritian political leaders, including Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, and the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Anthony Greenwood, coinciding with the Constitutional Conference of September 1965 in London. Over the course of three meetings, the Mauritian leaders pressed the United Kingdom with respect to the compensation offered for Mauritian agreement to the detachment of the Archipelago, noting the involvement of the United States in the establishment of the defence facility and Mauritius’ need for continuing economic support (for example through a higher quota for Mauritius sugar imports into the United States), rather than the lump sum compensation being proposed by the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom took the firm position that obtaining concessions from the United States was not feasible; the United Kingdom did, however, increase the level of lump sum compensation on offer from £1 million to £3 million and introduced the prospect of a commitment that the Archipelago would be returned to Mauritius when no longer needed for defence purposes. The Mauritian leaders also met with the Economic Minister at the U.S. Embassy in London on the question of sugar quotas, and Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam met privately with Prime Minister Harold Wilson on the morning of 23 September 1965. The United Kingdom's record of this conversation records Prime Minister Wilson having told Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam that[15]

in theory, there were a number of possibilities. The Premier and his colleagues could return to Mauritius either with Independence or without it. On the Defence point, Diego Garcia could either be detached by order in Council or with the agreement of the Premier and his colleagues. The best solution of all might be Independence and detachment by agreement, although he could not of course commit the Colonial Secretary at this point.

The meetings culminated in the afternoon of 23 September 1965 (the "Lancaster House Meeting") in a provisional agreement on the part of Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam and his colleagues to agree in principle to the detachment of the Archipelago in exchange for the Secretary of State recommending certain actions by the United Kingdom to the Cabinet. The draft record of the Lancaster House Meeting set out the following:[15]

Summing up the discussion, the SECRETARY OF STATE asked whether he could inform his colleagues that Dr. Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, Mr. Bissoondoyal and Mr. Mohamed were prepared to agree to the detachment of the Chagos Archipelago on the understanding that he would recommend to his colleagues the following:-

- (i) negotiations for a defence agreement between Britain and Mauritius;

- (ii) in the event of independence an understanding between the two governments that they would consult together in the event of a difficult internal security situation arising in Mauritius;

- (iii) compensation totalling up to [illegible] Mauritius Government over and above direct compensation to landowners and the cost of resettling others affected in the Chagos Islands;

- (iv) the British Government should use its good offices with the United States Government in support of Mauritius’ request for concessions over sugar imports and the supply of wheat and other commodities;

- (v) that the British Government would do their best to persuade the American Government to use labour and materials from Mauritius for construction work in the islands;

- (vi) that if the need for the facilities on the islands disappeared the islands should be returned to Mauritius. Seewoosagur Ramgoolam said that this was acceptable to him and Messrs. Bissoondoyal and Mohamed in principle but he expressed the wish to discuss it with his other ministerial colleagues.

Thereafter, Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam addressed a handwritten note to the Under-Secretary of State at the Colonial Office, Mr Trafford Smith, setting out further conditions relating to navigational and meteorological facilities on the Archipelago, fishing rights, emergency landing facilities, and the benefit of mineral or oil discoveries.[15]

On 6 October 1965, instructions were sent to the Governor of Mauritius to secure "early confirmation that the Mauritius Government is willing to agree that Britain should now take the necessary legal steps to detach the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius on the conditions enumerated in (i)–(viii) in paragraph 22 of the enclosed record [of the Lancaster House Meeting]." The Secretary of State went on to note that -[15]

5. As regards points (iv), (v) and (vi) the British Government will make appropriate representation to the American Government as soon as possible. You will be kept fully informed of the progress of these representations.

6. The Chagos Archipelago will remain under British sovereignty, and Her Majesty’s Government have taken careful note of points (vii) and (viii).

On 5 November 1965, the Governor of Mauritius informed the Colonial Office as follows:[15]

Council of Ministers today confirmed agreement to the detachment of Chagos Archipelago on conditions enumerated, on the understanding that

(1) statement in paragraph 6 of your despatch "H.M.G. have taken careful note of points (vii) and (viii)" means H.M.G. have in fact agreed to them.

(2) As regards (vii) undertaking to Legislative Assembly excludes (a) sale or transfer by H.M.G. to third party or (b) any payment or financial obligation by Mauritius as condition of return.

(3) In (viii) "on or near" means within area within which Mauritius would be able to derive benefit but for change of sovereignty. I should be grateful if you would confirm this understanding is agreed.

The Governor also noted that "Parti Mauricien Social Démocrate (PMSD) Ministers dissented and (are now) considering their position in the government." The Parties differ regarding the extent to which Mauritian consent to the detachment was given voluntarily.[15]

The detachment of the Chagos Archipelago was effected by the establishment of the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) on 8 November 1965 by Order in Council. Pursuant to the Order in Council, the governance of the newly created BIOT was made the responsibility of the office of the BIOT Commissioner, appointed by the Queen upon the advice of the United Kingdom FCO. The BIOT Commissioner is assisted in the day-to-day management of the territory by a BIOT Administrator.[15]

On the same day, the Secretary of State cabled the Governor of Mauritius as follows:[15]

As already stated in paragraph 6 of my despatch No. 423, the Chagos Archipelago will remain under British sovereignty. The islands are required for defence facilities and there is no intention of permitting prospecting for minerals or oils on or near them. The points set out in your paragraph 1 should not therefore arise but I shall nevertheless give them further consideration in view of your request.

On 12 November 1965, the Governor of Mauritius cabled the Colonial Office, querying whether the Mauritian Ministers could make public reference to the items in paragraph 22 of the record of the Lancaster House Meeting and adding "[i]n this connection I trust further consideration promised . . . will enable categorical assurances to be given."[15]

On 19 November 1965, the Colonial Office cabled the Governor of Mauritius as follows: U.K./U.S. defence interests;[15]

1. There is no objection to Ministers referring to points contained in paragraph 22 of enclosure to Secret despatch No. 423 of 6 October so long as qualifications contained in paragraphs 5 and 6 of the despatch are borne in mind.

2. It may well be some time before we can give final answers regarding points (iv), (v) and (vi) of paragraph 22 and as you know we cannot be at all hopeful for concessions over sugar imports and it would therefore seem unwise for anything to be said locally which would raise expectations on this point.

3. As regards point (vii) the assurance can be given provided it is made clear that a decision about the need to retain the islands must rest entirely with the United Kingdom Government and that it would not (repeat not) be open to the Government of Mauritius to raise the matter, or press for the return of the islands on its own initiative.

4. As stated in paragraph 2 of my telegram No. 298 there is no intention of permitting prospecting for minerals and oils. The question of any benefits arising therefrom should not [. . .] [illegible]7

There is no objection to Ministers referring to points contained in paragraph 22 of enclosure to Secret despatch No. 423 of 6 October so long as qualifications contained in paragraphs 5 and 6 of the despatch are borne in mind. 2. It may well be some time before we can give final answers regarding points (iv), (v) and (vi) of paragraph 22 and as you know we cannot be at all hopeful for concessions over sugar imports and it would therefore seem unwise for anything to be said locally which would raise expectations on this point. 3. As regards point (vii) the assurance can be given provided it is made clear that a decision about the need to retain the islands must rest entirely with the United Kingdom Government and that it would not (repeat not) be open to the Government of Mauritius to raise the matter, or press for the return of the islands on its own initiative.

A few weeks after the proposal to detach the islands from Mauritius, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 2066(XX) on 16 December 1965, which stated that detaching part of a colonial territory was against customary international law and the UN Resolution 1514 passed on 14 December 1960. This resolution stated that "Any attempt aimed at the partial or total disruption of the national unity and the territorial integrity of a country is incompatible with the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations."[17][18]

Depopulation[edit]

After initially denying that the islands were inhabited, British officials forcibly expelled approximately 2,000 Chagossians to mainland Mauritius to allow the United States to establish a military base on Diego Garcia. Since 1971, the atoll of Diego Garcia is inhabited by some 3,000 UK and US military and civilian contracted personnel. The British and American governments routinely deny Chagossian requests for the right of return.[19][20][21]

Marine protected area[edit]

A marine protected area (MPA) around the Chagos Islands known as the Chagos Marine Protected Area was created by the British Government on 1 April 2010 and enforced on 1 November 2010.[22][23] It is the world's largest official reserve, twice the size of Great Britain. The designation proved controversial as the decision was announced during a period when the UK Parliament was in recess.[24] Despite the official designation as a marine reserve, the US military is fully exempt from fishing restrictions[25] and the military base has been a major source of pollution to the area.[26]

A leaked diplomatic cable dating back to 2009 reveal the British and US role in creating the marine nature reserve. The cable relays exchanges between US Political Counselor Richard Mills and British Director of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office Colin Roberts, in which Roberts "asserted that establishing a marine park would, in effect, put paid to resettlement claims of the archipelago’s former residents." Richard Mills concludes:[27][28]

Establishing a marine reserve might, indeed, as the FCO's Roberts stated, be the most effective long-term way to prevent any of the Chagos Islands' former inhabitants or their descendants from resettling in the [British Indian Ocean Territory].

Resettlement study[edit]

In March 2014, it was reported that the UK government would send experts to the islands to examine "options and risks" of resettlement.[29]

Legal proceedings[edit]

Case before Permanent Court of Arbitration[edit]

The Government of Mauritius initiated proceedings on 20 December 2010 against the UK Government under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to challenge the legality of the ‘marine protected area’. Mauritius argues that Britain breached a UN resolution when it separated Chagos from the rest of the colony of Mauritius in the 1960s, before the country became independent, and that Britain therefore doesn't have the right to declare the area a marine reserve and that the MPA was not compatible with the rights of the Chagossians.[30][31] The dispute was arbitrated by the Permanent Court of Arbitration. The sovereignty of Mauritius was explicitly recognized by two of the arbitrators and denied by none of the other three. Three members of the Tribunal found that they did not have jurisdiction to rule on that question; they expressed no view as to which of the two States has sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago. Tribunal Judges Rüdiger Wolfrum and James Kateka held that the Tribunal did have jurisdiction to decide this question, and concluded that UK does not have sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago. They found that:[32]

- internal United Kingdom documents suggested an ulterior motive behind the MPA, noting disturbing similarities and a common pattern between the establishment of the so-called "BIOT" in 1965 and the proclamation of the MPA in 2010;

- the excision of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965 shows a complete disregard for the territorial integrity of Mauritius by the UK;

- UK Prime Minister Harold Wilson's threat to Premier Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam in 1965 that he could return home without independence if he did not consent to the excision of the Chagos Archipelago amounted to duress; Mauritian Ministers were coerced into agreeing to the detachment of the Chagos Archipelago, which violated the international law of self-determination;

- the MPA is legally invalid.

On 18 March 2015, the Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled that the Chagos Marine Protected Area was illegal.[33] The Tribunal's decision determined that the UK's undertaking to return the Chagos Archipelago to Mauritius gives Mauritius an interest in significant decisions that bear upon possible future uses of the archipelago. The result of the Tribunal's decision is that it is now open to the Parties to enter into the negotiations that the Tribunal would have expected prior to the proclamation of the MPA, with a view to achieving a mutually satisfactory arrangement for protecting the marine environment, to the extent necessary under a "sovereignty umbrella".[34]

Case before International Court of Justice[edit]

In 2004, following the decision of the British government to promulgate the British Indian Ocean Territory Order, which prohibited the Chagossians from remaining on the islands without express authorisation, Mauritius contemplated recourse to the International Court of Justice to finally and conclusively settle the dispute. However, article 36 of the International Court of Justice Statute provides that it is the option of the state whether it wishes to subject itself to the court's jurisdiction. Where the state chooses to be so bound, it may also restrict or limit the jurisdiction of the court in a number of ways. The UK's clause deposited at the court excluded, amongst other things, the jurisdiction of the court with regard "to any disputes with the government of any country which is a member of the Commonwealth with regard to situations or facts existing before 1 January 1969". The temporal limitation of 1 January 1969 was inserted to exclude all disputes arising during decolonisation. The effect of the British exclusionary clause would thus have prevented Mauritius from resorting to the court on the Chagos dispute because it is a member of the Commonwealth. When Mauritius threatened to leave the Commonwealth, the United Kingdom quickly amended its exclusion clause to exclude any disputes between itself, Commonwealth States and former Commonwealth States, thereby quashing any Mauritian hopes to ever have recourse to the contentious jurisdiction of the court, even if it left.[35]

On 23 June 2017, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) voted in favour of referring the territorial dispute between Mauritius and the UK to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in order to clarify the legal status of the Chagos Islands archipelago in the Indian Ocean. The motion was approved by a majority vote with 94 voting for and 15 against.[36][37] In September 2018, the International Court of Justice began hearings on the case. Seventeen countries have argued in favour of Mauritius.[38][39] The UK apologised for the "shameful" way islanders were evicted from the Chagos Archipelago but were insistent that Mauritius was wrong to bring the dispute over sovereignty of the strategic atoll group to the United Nations' highest court.[40] The UK and its allies argued that this matter should not be decided by the court but should be resolved through bilateral negotiations, while bilateral discussions with Mauritius have been unfruitful over the past 50 years.

In its 25 February 2019 ruling, the Court deemed the United Kingdom's separation of the Chagos Islands from the rest of Mauritius in 1965, when both were colonial territories, to be unlawful and found that the United Kingdom is obliged to end "its administration of the Chagos Islands as rapidly as possible."[41] Largely because of the detachment of the islands, the ICJ determined that the decolonization of Mauritius was still not lawfully completed.[42] On 1 May 2019, the UK Foreign Office minister Alan Duncan stated that Mauritius has never held sovereignty over the archipelago and the UK does not recognise its claim. He stated that the ruling was merely an advisory opinion and not a legally binding judgment. Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the UK's main opposition party, wrote to the UK PM condemning her decision to defy a ruling of the UN's principal court that concluded that Britain should hand back the Chagos Islands to Mauritius. He expressed his concern that the UK government appears ready to disregard international law and ignore a ruling of the international court and the right of the Chagossians to return to their homes.[43]

Case before International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea[edit]

On 28 January 2021, the United Nation's International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea ruled, in a dispute between Mauritius and Maldives on their maritime boundary, that the United Kingdom has no sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago, and that Mauritius is sovereign there. The United Kingdom disputes this and does not recognise the tribunal's decision.[44][45][46]

Diplomatic negotiations[edit]

In 2022, the United Kingdom initiated negotiations with Mauritius over the sovereignty of the islands[1] The move followed from talks between British prime minister Liz Truss and Mauritian prime minister Pravind Jugnauth in New York in October 2022.

Many Chagossian activists opposed the talks, as they did not include Chagossians as participants. In 2023, Bernadette Dugasse, a Chagossian activist, began legal proceedings against the British government, asking the High Court to order the government to allow Chagossian participation to the talks.[47] Some Chagossians are advocating for a referendum of Chagossians to determine the future of the islands.[48]

In September 2023, former British prime minister Boris Johnson argued that handing the Chagos to Mauritius would be a "colossal mistake".[49] In October 2023, a paper by three legal academics with a foreword by Admiral The Lord West of Spithead opposed the transfer of the Chagos to Mauritius and argued such a move would be a "major self-inflicted blow" for the United Kingdom.[50][51]

In December 2023, it was reported that the UK government was planning to discontinue the talks.[2]

See also[edit]

- List of sovereign states and dependent territories in the Indian Ocean

- Sovereignty disputes of the United Kingdom

- List of islands in Chagos Archipelago

- List of territorial disputes

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Wintour, Patrick (3 November 2022). "UK agrees to negotiate with Mauritius over handover of Chagos Islands". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Diver, Tony (1 December 2023). "UK drops plans to hand Chagos Islands back to Mauritius". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2 December 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ "Chagos remains a matter for discussion". Le Defimedia. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ "Time for UK to Leave Chagos Archipelago". Real clear world. 6 April 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ "Mauritius: MPA Around Chagos Archipelago Violates International Law – This Is a Historic Ruling for Mauritius, Says PM". allafrica.com/. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ Oliphant, Roland (3 September 2018). "International Court of Justice begins hearing on Britain's separation of Chagos islands from Mauritius". The Telegraph – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "What happened in Mauritius". www.telegraphindia.com.

- ^ "Chagos Dispute: critical Verdict Pertaining to the Future of its Inhabitants". Le Defi Media Group (in French). Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen (25 February 2019). "UN court rejects UK's claim of sovereignty over Chagos Islands". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ a b Sands, Philippe (24 May 2019). "At last, the Chagossians have a real chance of going back home". The Guardian.

Britain's behaviour towards its former colony has been shameful. The UN resolution changes everything

- ^ Osborne, Samuel (22 May 2019). "Chagos Islands: UN officially demands Britain and US withdraw from Indian Ocean archipelago". The Independent.

- ^ "ITLOS rejects all preliminary objections in Mauritius v. Maldives". fiettalaw.com. 28 January 2021.

- ^ "Press Release DISPUTE CONCERNING DELIMITATION OF THE MARITIME BOUNDARY BETWEEN MAURITIUS AND MALDIVES IN THE INDIAN OCEAN (MAURITIUS/MALDIVES)" (PDF). International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. 28 January 2021.

- ^ Cleverly, James (3 November 2022). "Chagos Archipelago". Hansard. UK Parliament. HCWS354. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y "IN THE MATTER OF THE CHAGOS MARINE PROTECTED AREA ARBITRATION – before – AN ARBITRAL TRIBUNAL CONSTITUTED UNDER ANNEX VII OF THE UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON THE LAW OF THE SEA – between – THE REPUBLIC OF MAURITIUS – and – THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND" (PDF). Permanent Court of Arbitration. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ "Constitution of Mauritius" (PDF). National Assembly (Mauritius). March 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2066 (XX) - Question of Mauritius". United Nations. 16 December 1965. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ "2.4 Self-determination". Exploring the boundaries of international law. The Open University. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ "Commonwealth Secretariat — British Indian Ocean Territory". Thecommonwealth.org. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ "HISTORICAL BACKGROUND – WHAT HAPPENED TO THE CHAGOS ARCHIPELAGO ?". chagosinternational.org. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ "Neutral Citation in the Royal Courts of Justice, London" (PDF). Government of Mauritius. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ "Protect Chagos". Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ "Chagos Archipelago becomes a no fishing zone". phys.org. 1 November 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (1 April 2010). "UK sets up Chagos Islands marine reserve". BBC News. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen; Vidal, John (28 January 2013). "Britain faces UN tribunal over Chagos Islands marine reserve". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "WikiLeaks Cables Reveal Use of Environmentalism by US and UK as Pretext to Keep Natives From Returning to Diego Garcia". Institute for Policy Studies. 3 December 2010. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ Murphy, Cullen (15 June 2022). "They Bent to Their Knees and Kissed the Sand". The Atlantic. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ "US embassy cables: Foreign Office does not regret evicting Chagos islanders". The Guardian. 2 December 2010. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ Vidal, John (13 March 2014). "Chagos islands: UK experts to carry out resettlement study". Retrieved 25 February 2019 – via Theguardian.com.

- ^ "STATEMENT BY DR THE HON. PRIME MINISTER TO THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY" (PDF). Government of Mauritius. 31 May 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 November 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ "Chagos marine reserve challenged at tribunal". The UK Chagos Support Association. 22 April 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ^ "In the Matter of the Chagos" (PDF).

- ^ "Permanent Court of Arbitration finds U.K. In Violation of Convention on the Law of the Sea in Chago Archipelago Case (March 18, 2015) | ASIL".

- ^ "Sixth National Assembly Parliamentary Debates(Hansard)" (PDF). National Assembly (Mauritius). 20 March 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Reddi, Vimalen (14 January 2011). "The Chagos Dispute: Also Giving Law A Chance". Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ Sengupta, Somini (22 June 2017). "U.N. Asks International Court to Weigh In on Britain-Mauritius Dispute". The New York Times.

- ^ "Chagos legal status sent to international court by UN". BBC News. 22 June 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ Oliphant, Roland (3 September 2018). "International Court of Justice begins hearing on Britain's separation of Chagos islands from Mauritius". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ "What happened in Mauritius". The Telegraph (India).

- ^ "Chagos Dispute: critical Verdict Pertaining to the Future of its Inhabitants". Le Defi Media Group (in French). Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen (25 February 2019). "UN court rejects UK's claim of sovereignty over Chagos Islands". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ "Legal Consequences of the Separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965 - Overview of the case". International Court of Justice. 25 February 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen (1 May 2019). "Corbyn condemns May's defiance of Chagos Islands ruling". The Guardian.

- ^ Harding, Andrew (28 January 2021). "UN court rules UK has no sovereignty over Chagos islands". BBC News. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Dispute Concerning Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary between Mauritius and Maldives in the Indian Ocean (Mauritius/Maldives)" (PDF) (Press release). International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. 28 January 2021. ITLOS/Press 313. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Dispute Concerning Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary between Mauritius and Maldives in the Indian Ocean - Judgment" (PDF). International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. 28 January 2021. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ Boffey, Daniel (9 January 2023). "Negotiations on Chagos Islands' sovereignty face legal challenge". The Guardian.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen (13 January 2023). "The UK expelled the entire population of the Chagos Islands 50 years ago. Reversing that injustice won't be easy". Prospect.

- ^ Gutteridge, Nick (22 September 2023). "Boris Johnson says handing over Chagos Islands will be 'colossal mistake'". The Telegraph.

- ^ Swinford, Steven (27 October 2023). "Giving up Chagos Islands 'would threaten Falklands'". The Times.

- ^ Zhu, Yuan Yi; Grant, Tom; Ekins, Richard (2023). Sovereignty and Security in the Indian Ocean: Why the UK should not cede the Chagos Islands to Mauritius. Policy Exchange.

External links[edit]

- Who Owns Diego Garcia? Decolonisation and Indigenous Rights in the Indian Ocean

- Ruling of THE UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON THE LAW OF THE SEA ARBITRAL TRIBUNAL about the CHAGOS MARINE PROTECTED AREA

- Loft, Philip (22 November 2022). "British Indian Ocean Territory: UK to negotiate sovereignty 2022/23" (PDF). House of Commons Library. UK Parliament.

- Let Us Return USA!

- Film and video

- Chagos: A Documentary Film

- Stealing a Nation (TV documentary, 2004), a Special Report by John Pilger

- Chagos Archipelago sovereignty dispute

- Chagos Archipelago

- British Indian Ocean Territory

- Politics of Mauritius

- Politics of the Maldives

- Maldives and the Commonwealth of Nations

- Mauritius and the Commonwealth of Nations

- Mauritius–United Kingdom relations

- Maldives–United Kingdom relations

- Maldives–Mauritius relations

- Territorial disputes of the United Kingdom

- Territorial disputes of the Maldives

- Territorial disputes of Mauritius

- United Kingdom and the Commonwealth of Nations

- Sovereignty

- International disputes