Armenians in the Byzantine Empire

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Byzantine Empire (Anatolia, Constantinople, European part of the Empire) | |

| Languages | |

| Armenian and Greek | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Armenian Apostolic Church, Chalcedonians | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Armenians |

Armenians in the Byzantine Empire (Armenian: Հայերը Բյուզանդիայում) were the most significant ethnic minority at some times. Historically, this was due to the fact that part of historical Armenia, west of the Euphrates, was part of Byzantium. After the division of Armenia between the Roman Empire and the Sasanian Empire in 387, part of Greater Armenia was annexed to the Empire. At this time and later, there were significant migrations of Armenians to Byzantine Anatolia, Constantinople and the European part of the Empire. The Armenians occupied a prominent place in the ruling class of Byzantium, with a number of emperors coming from their ranks: Heraclius I (610–641), Philippicus (711–713), Artabasdos (742–743), Leo the Armenian (813–820), Basil I Macedonian (867–886) and the dynasty he founded, Romanos I Lekapenos (920–944) and John Tzimiskes (969–976). According to the calculations of Alexander Kazhdan, Armenians made up 10–15% of the ruling aristocracy in the 11th–12th centuries; taking into account persons and families whose Armenian origin is not entirely certain, this proportion becomes much higher. Due to the fact that Armenia did not recognise the Fourth Council of Chalcedon (451), the relations between Byzantium and Armenia were influenced by the attempts of the official Byzantine Church to convert the Armenian Church to Chalcedonian Armenians. Many Armenians played an important role in the Greco-Roman world and in Byzantium.[1]

Armenian population of Byzantium

[edit]Armenian migrations to Byzantium

[edit]

The presence of Armenians in the territory of the Roman Empire is known from the beginning of the first century. The geographer Strabo reports that "Comana has a large population and is an important trading centre for merchants from Armenia".[2] In the 4th and 5th centuries, the Armenian population appeared in other regions and cities of the Empire.[3] In 571, fleeing persecution in the Sasanian Empire, many Armenians, led by Vardan Mamikonian, found refuge in Byzantine Anatolia and in particular in the city of Pergamum, where they formed a large colony.[4] In the middle of the 7th century, the Pavlicians fled to Byzantium and settled at the confluence of the Iris and Lycus rivers in the diocese of Pontus. Under Constantine V (741–775), many Nakharars left their possessions in Armenia and fled to Byzantium.[5] In 781, fleeing persecution in the Caliphate, 50,000 Armenians migrated to Byzantium. Empress Irene and her son Constantine VI (780–797) officially welcomed them in Constantinople and rewarded those who arrived with titles and lands according to their nobility.[6]

Forced relocations of Armenians were also practised. They were probably not significant until the middle of the 6th century, although Procopius of Caesarea, reporting on the reasons for the discontent of a certain Arsacus, says that during the Gothic War, Armenia was "... tormented by constant recruitment and military fasting, exhausted by extraordinary taxes, his father executed on the pretext of non-fulfilment of treaties and agreements, all his relatives enslaved and scattered throughout the Roman Empire".[7] During the reign of Tiberius II (578–582), 10,000 Armenians from Arzanene were resettled in Cyprus.[8] Sebeos reports the plans of his successor Maurice (582–602) to solve the problem with the Armenians, who were "a stubborn and unruly people, living among us and muddying the waters". To this end, the Byzantine emperor entered into correspondence with Shah Khosrow II (591–628), proposing that he should simultaneously carry out the resettlement of the Armenians subject to him, while Maurice would resettle his own in Thrace. However, the result was somewhat different, as the Armenians began to flee to Persia.[9] Thrace was later considered the most suitable place for Armenians to live: under Constantine V (741–775) Armenians and Syrian Monophysites were resettled there, under Leo IV (775–780) 150,000 Syrians were resettled there, among whom could be Armenians.[10] After the victory of Basil I (867–886) in 872 over the Pavlikians, most of whom were probably Armenians, many of them were scattered throughout the empire. Under his son, Leo VI, the Armenian ruler Manuel of Tekis was "brought to Constantinople",[11] most likely indicating that he was forcibly detained, and his four sons were given lands and offices. Manuel himself was given the title of protospatharius and the theme of Mesopotamia[12] was founded on his former lands. Under John Tzimiskes (969–976) the Paulicians were moved from the eastern provinces to Thrace. Basil II (976–1025) also moved many Armenians from his subject lands to the region of Philippopolis and Macedonia in order to organise defence against the Bulgarians.[13] Asoghik reports in the early 11th century that "... the latter intended to resettle some of the Armenians under his rule in Macedonia [in order to set them] against the Bulgars [and to give them the opportunity to participate in] the organisation of the country".[14]

Thrace was not the only place where Armenians settled: they are mentioned in the early 11th century among the peoples resettled by Nikephoros I (802–811) in Sparta to rebuild the ruined city; in 885 the commander Nikephoros Phokas the Elder resettled many Armenians, probably Pavlicians, in Calabria. After the conquest of Crete in 961, Armenians were also settled there.[15] In 1021, the king of the Armenian Vaspurakan kingdom, Senekerim Artsruni, transferred his kingdom to Byzantium. He received Sebastia, Larissa and Avara for it and became patrician and stratigem of Cappadocia. With him, 400,000 people[16] migrated from Vaspurakan to Cappadocia. This figure, first mentioned in the 18th century by the Armenian historian M. Chamchyan, is questioned by the contemporary Armenist Peter Charanis, as a contemporary source gives the number of settlers as 16,000, not counting women and children. From the middle of the 10th century, Armenians began to settle intensively in Cappadocia, Cilicia and northern Syria.[17] Many Armenian refugees made their way to Byzantium to escape Seljuk raids. The defeat of Byzantium at Manzikert in 1071 and the conquest of territories in Asia Minor by the Crusaders at the end of the 11th century led to a diminished role for the Armenians, although their presence is recorded until the final fall of the empire. Armenian colonies in the last period of Byzantine history are known in the remaining cities of Anatolia under Byzantine rule and in the European provinces.[18]

The mass resettlement of Armenians from Armenia to Byzantine lands had more global consequences than the growth of the community. In the second half of the 11th century, Armenians formed at least 6 states here: in 1071 the state of Filaret Varažnuni and the Principality of Melitene, in 1080 the Principality of Cilicia, in 1083 the Principality of Edessa, around the same time — the Principality of Kesun and the Principality of Pir. Of these, the Principality of Cilicia was recognised as an Armenian kingdom in 1198. Mekhitar Ayrivank wrote in the 13th century: "At that time the Rubenians began to rule in Cilicia. God Himself did justice to us who were oppressed: the Greeks ceased our kingdom, but God gave its land to the Armenians, who now reign in it".[19]

The Armenian possessions in the Empire

[edit]

After the first partition of Armenia in 387, about a quarter of the Armenian Kingdom of the Arsacid was incorporated into Byzantium. This gave the empire a significant Armenian population. At the same time, they were one of the indigenous peoples of Cappadocia. With the support of Byzantium, which sought to strengthen its influence in the region, Christianity continued to spread in Armenia. In the Byzantine part of Armenia, Mashtots, the creator of the Armenian alphabet, was active in the 420s. After the end of the Iranian-Byzantine war in 591, the second division of Armenia took place,[20] as a result of which the Byzantine border moved eastwards and covered the whole of central Armenia.[21] Around 600 rebellions started in Armenia, then from 603 Armenia was involved in another war between Byzantium and Iran.[22] Around 640, the Muslim conquest of Armenia began and soon this part of the empire was lost.[23] In the 10th century, significant areas with Armenian populations were incorporated into the Byzantine Empire.[24] Thus in 949 the region of Karin was annexed, in 966 the Armenian principality of the Bagratids in Taron,[25] and a few years later Malazgirt, also with a predominantly Armenian population.[26] A turning point in the further history of the Armenian people was the annexation of the kingdom of Ani in central Armenia by the Empire in 1045 and the occupation of the great city of Ani. For a time, the Byzantine Empire's possessions in Armenia reached as far as the western coast of Sevan. However, this situation did not last long. In 1064 this territory was conquered by the Seljuk Sultan Alp-Arslan. The following year, King Gagik of Vanand was forced to surrender his kingdom to Byzantium. By 1065, much of historical Armenia, with the exception of Ani, Syunik, Tashir and Khachen, was part of Byzantium.

The mass annexation of Armenian lands by Byzantium had far-reaching consequences. On the one hand, Byzantium was deprived of a buffer, and any invasion from the east now directly affected its territory, which meant the inevitable involvement of the empire in a conflict with the Seljuks. In addition, in an attempt to integrate the indigenous Armenian nobility into the new Byzantine reality, the Empire was forced to allocate lands in Lycandus, Cappadocia, Tsamandos, Harsianon, Cilicia and Mesopotamia to the displaced Armenian princes. Tens of thousands of Armenian peasants and artisans migrated with these princes, changing the ethnic and religious composition of these provinces. This in turn led to a fierce struggle with the Greek Orthodox population already present there.[26]

Legal status

[edit]Lesser Armenia became a Roman province under Vespasian (69–79), first as part of Cappadocia, then separately. Not much information has survived about this province, but it could be not very different from the others. In the territories acquired after 387, the power of the Arsacids was abolished either immediately or under Theodosius II (402–450) and transferred to the comes of Armenia. At the same time, the hereditary rights of the Nakharars to the land and its transfer on the basis of the principle of majorat were respected. The territories in the bend of the Euphrates were only nominally subject to the Arsacids from 298; their rulers were directly subordinate to the emperor, and local military contingents were under their command. All parts of Armenia paid taxes to the treasury. During the reign of Justinian I (527–565), changes were made to the administrative structure of Armenia, taxation was increased and women were given the right of inheritance. This last measure led to the fragmentation of the possessions of the Nakharars, which led to their discontent.[27]

The Muslim conquest of Armenia in the 7th century did not change the general tendency to integrate the Armenian nobility into the administrative structures of the empire. In the areas conquered in the 10th and 11th centuries, themes were established, with command positions given not only to Armenians from the interior provinces, but also to local natives. In its activities, Byzantium relied not only on the Chalcedonian Armenians who were close in faith, but also on those who remained loyal to the Armenian Church.[28]

Armenian prosopography of Byzantium

[edit]Emperors

[edit]

A rather extensive literature is devoted to attempts to establish the Armenian origin of various Byzantine emperors. According to the Armenian historian Leo, this “flattered the national vanity of Armenians”.[29] The first Byzantine emperor about whom there is a legend regarding his Armenian origin is Maurice (582–602). A number of Armenian historians of the 10th–13th centuries provide information about his Armenian origin, from Oshakan, according to Asoghik.[30] In the same locality, there is a column, according to local legend, erected in honor of the emperor's mother.[31] The analysis of these legends was conducted by N. Adontz, who supported recognizing their authenticity. Nevertheless, the majority of modern researchers recognise the perspective of Evagrius Scholasticus, who asserts that Maurice “by descent and name, originated from ancient Rome, and by his immediate ancestors, his homeland was the Cappadocian city of Aravin”.[32][33] According to the authors of the Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, this question remains unsolved.[34]

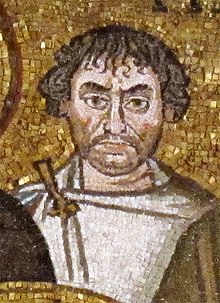

More reliable information concerns Emperor Heraclius I (610–641). The historian of the 7th century, Theophylact Simocatta, in his History, states that the native city of this emperor was in Armenia.[35] It is known that during the last Iranian-Byzantine war, the residence of Heraclius from 622 to 628 was in Armenia.[36] In the History of Emperor Heraclius by the 7th-century Armenian historian Sebeos, Heraclius' kinship with the Arsacids is mentioned, although the degree of this kinship is not quite clear.[37] Other versions of the origin of this emperor propose his African, Syrian, or Cappadocian non-Armenian origin, and each of these possibilities suggests a different interpretation of the deeds of this outstanding ruler.[38] In the authoritative reference book Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, the origin of Heraclius is identified simply as Cappadocian, which does not exclude Armenian ancestors.[39] The usurper Misisius, who ruled in Sicily in 668–669, was Armenian. His name is a Greek transcription of the Armenian name Mzhezh. Very little is known about the brief reign of Philippicus (711–713) in the years following the turmoil that began after the first overthrow of Justinian II. Assertions about his Armenian origin are based on his birth name, Vardan. A source from the middle of the 8th century refers to his father, Nikephoros, as a native of Pergamum. However, as A. Stratos notes, there is no contradiction between the information about the origin of Philippicus' family from Pergamum and his Armenian roots, since in 571 many Armenians fled to Anatolia and founded a large colony in Pergamum.[4] According to C. Toumanoff, Emperor Artavazd (742–743) belonged to the noble Mamikonian family.[40] Regarding the origin of Emperor Leo V the Armenian (813–820), the Continuer of Theophanes states: "The fatherland of the said Leo was Armenia, but he was descended on the one hand from Assyrians, and on the other hand from Armenians, those who in a criminal and impious scheme shed the blood of their parents, were condemned to exile and, living as fugitives in poverty, raised this beast".[41] Such an unflattering characterization may be due to doctrinal differences between the author of the chronicle and the iconoclastic emperor.[42] According to K. Toumanoff, this emperor belonged to the noble Armenian family of Gnuni,[40] and this viewpoint is considered probable by W. Treadgold.[43][44] There is also an opinion that he belonged to the Artsrunids.[45] Empress Theodora had Armenian roots, along with her brothers, uncle, nephews, and other numerous relatives who exercised regency during the minority of her son, Michael III (842–867).[46][47] According to N. G. Adontz, she belonged to the Nakharar Mamikonian family.[48]

The question of the origin of Emperor Basil I (867–886) has attracted the close attention of Byzantinists since the time of Ducange. In the opinion of this 17th-century French researcher, the genealogy presented by Patriarch Photios, tracing Basil’s paternal line to relatives of the Armenian tsars who moved to Byzantium under Emperor Leo Machella (457–474), and his maternal line to Constantine the Great (306–337), is entirely fictitious.[50] In the 19th century, based on the study of Arabic sources, the theory of Basil I’s Slavic origin was developed. Thus, the total number of hypotheses reached three: noble Armenian, low-born Armenian, and Slavic. It is known that Basil's birthplace was near Adrianople, where both Slavs and Armenian Paulicians could have lived.[51] The Vita Euthymii (the first half of the 10th century), discovered in the 19th century, speaks quite definitively about Basil’s Armenian origin.[52] On the other hand, there are strong arguments against Photius’ account, also echoed by Genesius and Basil's grandson, Constantine VII (913–959).[53] A number of Greek texts are aware of Basil’s humble origins but do not mention his Armenian roots.[54] Armenian sources are unanimously convinced of Basil's Armenian origin, and Asolik, for example, writes about his son: "Leo VI, as the son of an Armenian, surpassed any Armenian tarovatostvo",[55] and Vardan that "he was the son of an Armenian and very fond of Armenians".[56] Comparing all known at the beginning of the 20th century, the well-known Russian Byzantinist A. A. Vasiliev tends to the version about the Armenian ignorant origin of Basil I, considering the indications about his possible Slavic origin as a consequence of confusion because of the geographical location of the province of Macedonia inhabited mainly by Slavs.[56] According to this opinion, it is widely believed that all the representatives of the Macedonian dynasty founded by him until Basil II (867–1025) were of Armenian origin.[57] This is now the prevailing theory.[58] It was opposed by the Byzantinist G. A. Ostrogorsky.[59]

Some emperors in the 10th century include Romanos I Lekapenos (920–944)[60] and John I Tzimiskes (969–976).[61] The Armenian origin of the Phokas family, to which Emperor Nicephorus II Phocas (963–969) belonged, is not reliably confirmed.[62]

Aristocratic families

[edit]After the partition of Armenia in 387, Byzantium acquired not only territory but also a significant portion of the Armenian aristocracy, that entered both military and civil service. A new influx of nobility occurred after the second partition of Armenia in 591 and the Muslim conquest of Armenia in the 7th century. According to N. G. Adontz, “all Armenians who played a certain role in Byzantine history almost entirely belonged to the class of Armenian nobility”. When considering the question of the affiliation of historical figures to specific noble families, the difficulty lies in the fact that Greek sources usually did not reflect this detail.[63]

Numerous Byzantine aristocratic families had Armenian origin, including the Lekapenos, Kourkouas, Gabras, Zautzes, and many others, whose representatives held high civil and military positions. Alexander Kazhdan conducted a study of aristocratic families of Armenian origin during the 11th–12th centuries. According to his classification, we can distinguish three categories of such families: those whose Armenian origin is indisputable, Armenian-Ivir families, and other families for which the origin is difficult to establish.[64] According to A. P. Kazhdan’s estimate, made in the 1970s, the share of descendants from natives of Armenia during the period he studied was between 10 and 15 percent.[65] As a result of further research, N. Garsoyan considered this estimate overestimated.[66] Alongside the Armenian aristocracy of Byzantium, there is also the ‘Armenian-Ivirian,’ i.e., those whose representatives are referred to in Byzantine sources as Armenians and Ivirs. It is believed that these families, which Kazhdan attributed to the Tornikov and Pakurianov, and which N. G. Garsoyan also attributed to the Phokas, belonged to the Chalcedonian nobility of the theme of Iberia, whose ethnic origin could be diverse.[67][68]

From the 8th to the 10th century, the Armenian family of Mosile produced a number of significant military commanders.[69] The Chronicle of the Theophanes Continuatus repeatedly mentions Constantine Maniakes, “the father of our logothete of the dromos, wise philosopher and absolutely incorruptible patrician Thomas”. The chronicler also notes that this Constantine was friendly with the future Emperor Basil I due to their shared Armenian origin.[70][71] In the mid-9th century, the effective ruler of the Byzantine Empire was Bardas, a younger brother of Empress Theodora, the Armenian, possibly from the Mamikonian family. After the 9th century, information about Armenian aristocratic families becomes quite abundant. Among the Armenian families of the late Byzantine period, we can name the Taronites (10th–13th centuries) and their relatives, the Tornikios, who remained influential until the 14th century. A representative of the Tornikios family was the 11th-century usurper Leo Tornikios.[72]

Figures of culture and science

[edit]There is information about the Armenian philosopher-sophist Prohaeresius since the Roman era.[73] In the Byzantine Empire, some representatives of science and culture also had Armenian origins. In the 7th century, having learned in his homeland “all the literature of our Armenian people”, the Armenian geographer Anania Shirakatsi, according to the French Byzantinist P. Lemerle, —the father of the exact sciences of Armenia— went to Byzantium to continue the education. At first, he intended to study with the mathematician Christosatur (it is impossible to say for certain whether he was Armenian), in the province of Armenia IV. His compatriots then advised him to go to Trabzon, where the scholar Tikhik, knowledgeable in sciences and fluent in Armenian, lived. For eight years, Anania studied with this Greek scholar, translating Greek texts to Armenian.[74] After completing his studies, Anania returned to Armenia, where he began teaching, disheartened to find that Armenians “do not like learning and science”. Anania was not happy about this. Regarding this story, reported by Anania in his autobiography, various hypotheses have been put forward — either that the young Armenians studying in Trebizond were to be later chirotonized, or that Tikhik was taught by Greeks, whom Byzantium, as part of the Armenian policy of Emperor Heraclius I, wanted to involve in Armenian affairs.[75]

Armenians played an important role in the cultural and intellectual life of Constantinople.[76] A native of Constantinople, to whom Armenian origin is commonly attributed, was John Grammaticus — Patriarch of Constantinople from 837 to 843 and a famous iconoclast. The names of his brother (Arshavir) and father (Bagratuni, in Greek sources—Pankratios) indicate a probable kinship with the Bagratuni and Kamsarakan dynasties.[77] Among the Byzantine scientists of Armenian descent, the author of the famous monograph on Armenians in Byzantium, P. Charanis, names the patriarch of the 9th century, Photios,[78] but in most modern sources, the origin of this prominent religious figure and encyclopaedist is not specified due to insufficient extant data.[79] A well-known patron of the sciences in the 9th century was the major statesman Bardas.[80] His friend and co-founder of the University of Constantinople was Leo the Mathematician, nephew of John the Grammarian.[78][81] Some sources mention the Armenian ancestry of Joseph Genesius.[82] Such a claim is based on the probable Armenian origin of his grandfather, Constantine Maniak,[83] but the kinship between Joseph Genesius and Constantine Maniak is sometimes questioned.[84] Apparently, the writer of the 11th century, Kekaumenos, author of the famous Advice and Stories, containing not only military but also domestic teachings, was also of Armenian descent.[85] During the Palaeologan Renaissance, the mathematician of Armenian origin, Nicholas Artavazd, was active.[86]

Armenians in the Byzantine army

[edit]

It is known that Armenians used to be merchants and representatives of other professions, their main occupation in Byzantium seems to have been military service.[87] Thanks to the information from Procopius of Caesarea, the court historian of Emperor Justinian I, the role of Armenians in the wars that the emperor fought in Africa against the Vandals, in Italy against the Ostrogoths, and in the Middle East against the Sassanids is well documented. Besides Narses, a native of Persoarmenia who achieved considerable success in the war with the Goths and in conflicts with the Antes, Heruli, and Franks,[88] about 15 commanders of Armenian origin in Justinian’s army can be mentioned.[89] The Byzantine garrison of Narses, located in Italy, consisted mainly of Armenians and was called numerus Armeniorum.[90] According to the Armenian historian Sebeos, the Armenian element dominated the polyethnic army of Emperor Maurice:[91] “He ordered to transport all of them across the sea and unite them in the countries of Thrace against the enemy". At the same time, he also ordered the gathering of all the Armenian cavalry and the princes of the Nakharars, who were powerful in battle and skilled both in warfare and in throwing spears. He also commanded the recruitment of a strong army from Armenia, selecting the tallest and most skilled hunters to form slender regiments, arm them, and send them to Thrace against the enemies, appointing Mushegh Mamikonyan as their commander.[92] This campaign beyond the Danube ended with the defeat of the Byzantines and the death of Mushegh. After that, two armies of 1,000 horsemen each were recruited in Armenia, of which one “was frightened on the road and did not want to go to the place where their king demanded them”.[93][94] According to the 19th-century historian K. P. Patkanov, starting from the reign of Maurice, Armenian commanders began to play an important role in the Greek army, reaching the highest command positions.[94]

During the reign of Heraclius I, the significant role of Armenians in the army was preserved, along with other Caucasian peoples—Lazs, Abasgois, and Iberians.[94] Theophanes the Confessor, in connection with Heraclius I’s campaign against the Persians in 627/628, twice mentions the participation in this campaign of a detachment of Armenian cavalry under the command of the turmarch George.[95] Under Heraclius, the Armenian Manuel served as prefect of Egypt. Some of the usurpers of the 7th century may have been Armenians — Vahan, proclaimed emperor before the battle of Yarmouk, and the Opsician comite Misisius, who was proclaimed emperor during the reign of Constantine II (641–668) for his “plausibility and majesty”.[96] An Armenian was also proclaimed emperor during the reign of Constantine II (641–668). According to Michael the Syrian, his Armenian name was Mzhezh Gnuni, and his son John revolted against Constantine IV (668–685). After the completion of the conquest of Armenia by the Arabs, the Armenian troops were spared from fighting against their co-religionists, because according to the terms of the treaty concluded in 652, the Armenian cavalry could not be transferred to the Syrian front.[97] Around 750, Tachat Andzevatsi arrived in Byzantium and fought successfully in Constantine V’s wars against the Bulgarians; he later became a commander in the fief of Bucellarian.[98] Emperor Leo the Armenian's relative —General Gregory Pterot— had a successful military career during his uncle's lifetime and, after his assassination, attempted to join the revolt of Thomas the Slav. Michael the Amalekite served four emperors, from Michael I (811–813) to Theophilus (813–842), in the ranks of protostrator, strategus of the Armeniacon, and domestikos of the schola.[99] In 896, Nakharar Melias (died in 934), known in Byzantine sources as Melia and possibly the grandson of Ishkhan Varažnunik, entered Byzantine service.[100] In 908, Mlekh was commissioned to rebuild the fortress of Likand and the garrisons in its vicinity, leading many Armenians to move to this region. In 916, a theme was organized here, whose army participated in another failed battle against the Bulgarians.[101] Mlekh himself, “thanks to the loyalty he showed to the Vasileus of the Romans and his many endless exploits against the Saracens”, was honored with the title of Master.[102]

In the formation of the theme a military-administrative system, the Armeniac Theme was created as one of the first, but the dating of this event is a debated.[103] In the 7th century, the epithet “God-protected imperial” (Ancient Greek: θεοφύλακτος βασιλικός) was applied to this theme, indicating its special “elite” status.[104] From the end of the 9th century, the combat effectiveness and role of the old theme diminished,[105] with their decline continuing until the 1030s.[106] In the 10th century, a prominent military figure of the empire was the Armenian John Kourkouas, a representative of the Kourkouas family.[57] Based on the assumption that the military contingent of Armeniacon consisted mainly of Armenians and that its size was between 18,000 and 23,000 people, we can estimate that the share of Armenians in the Byzantine army of the 9th–11th centuries was about 20%.[107]

However, sources testify that Armenians were not the most disciplined part of the Byzantine army during certain periods. In an anonymous military treatise, De velitatione bellica, attributed to Emperor Nikephorus II, it is especially noted that “Armenians are not good and are careless in fulfilling the position of guards”.[108] They often deserted and did not always obey orders.[109] During the Battle of Manzikert (1071), which ended in a disastrous defeat for the Byzantines, the Armenian contingent of the army deserted.[110] The reasons for this low loyalty can be explained by the incessant pressure in the religious sector.[111]

Place in the society

[edit]Religion

[edit]

In the early 4th century, Armenia became a Christian community, and since then, the church became a powerful organization; its role was particularly important in periods of loss of state autonomy.[112] Armenia did not recognize the decisions of the Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon in 451, thereby breaking away from the church of the rest of Byzantium. Although the Armenian Church accepted the Christological formula of Cyril of Alexandria, the condemnation of the Council of Chalcedon made it monophysite, i.e., heretical from the perspective of Constantinople. In turn, the Armenian Church considered the supporters of the Council of Chalcedon as Nestorians, i.e., supporters of the heresiarch Nestorius, who was condemned by the Council of Ephesus (431).[113] Since public service presupposed the adoption of the state religion, most of the known Armenians in the service of the empire were Chalcedonites.[114]

Attempts to restore ecclesiastical unity were made in the early 7th century, again in the 9th century by Patriarch Photius, and in the 12th century in relation to Cilician Armenia.[115] For example, in the middle of the 9th century, on the eve of the recognition of the independence of the Bagratid Armenia by the Caliphate and Byzantium, the Empire, through Patriarch Photius, raised the dogmatic question, suggesting that Armenians accept Chalcedonism. The Council of Shirakavan, convened around 862 and headed by Catholicos Zacharias I of Armenia, rejected this proposal.[116][117] Inter-confessional contradictions sometimes escalated to such an extent that in the middle of the 10th century, the Armenian Catholicos Ananias Mokatsi asked King Abas of Armenia to ban marriages with Chalcedonites.[118]

Persecution of non-Chalcedonites, including Armenians and Syriacs, intensified in the 11th century. In 1040, relations between Greeks and Syrians in Melitene escalated, prompting the patriarch of Constantinople to respond by condemning marriages between Orthodox and Monophysites. In 1063, Constantine X Doukas ordered all those who did not recognize the Council of Chalcedon to leave Melitene, and a few months later, the liturgical books of the Syrian and Armenian churches were burned. In 1060, Catholicos Khachik II and several bishops were summoned to Constantinople and forcibly detained until 1063.[119] The dogmatic issue became acute again in the 12th century under Catholicos Nerses IV Shnorali. The Church Council convened in 1179 by Catholicos Gregory IV condemned the extremes of Monophysitism but rejected the doctrine of two wills and two influences, affirming the Armenian Church's interpretation of the one hypostasis of God the Word Incarnate. In the words of Vardan the Great, “They wished for the unity of the two peoples: Greeks and Armenians; but the enterprise failed, as can be seen in the detailed accounts of historians”.[120]

The heretical Christian movement of the Paulicians, originating in the 6th or 7th century, spread throughout the regions of Byzantium populated by Armenians. Armenians were probably the majority among the followers of this doctrine, which's name has Armenian origin. The Paulicians were constantly persecuted; the state founded by them in Western Armenia was destroyed by Emperor Basil I in 872, and more than 100,000 sectarians were killed.[121]

Relationship with other ethnic groups

[edit]Together with the Jews and Italians, the Armenians were one of the three most economically wealthy groups in the Byzantine Empire.[76] The author of Historical Dictionary of Byzantium, J. Rosser, notes that Armenians became the most adapted ethnic group in Byzantium, who, at the same time, preserved their original literature, religion, and art.[122]

Some historical sources testify to a certain distrust and even prejudice of the Byzantines towards Armenians. Many Byzantine writers considered it necessary to point out that some prominent persons of the empire were Armenians or of Armenian origin.[76] The fact that the tension between Armenians and Greeks was not only caused by religious differences is evidenced by a 9th-century epigram attributed to the nun Kassia, which states that “the Armenian race is the most horrible”.[123][124] In 967, according to the Byzantine historian Leo the Deacon, “a massacre took place between the inhabitants of Byzantium and the Armenians”.[125][126] The example of hostility between the Greek and Armenian populations of the empire is well known in the Armenian colony near the city of Abydos. The discontent of the local Greeks was probably caused by the resettlement of Armenians from other regions after the conquest of Anazarbus from the Crusaders by John II Komnenos in 1138. When, after the sack of Constantinople in 1204, Henry I of Flanders crossed into Anatolia to continue his conquests for the Latin Empire, the Armenians of Abydos helped him take the city. Henry then entrusted them with the defense of the city, and the Armenians followed him after leaving Anatolia. Villardouin's chronicle reports that 20,000 Armenians migrated to Thrace, where they were overtaken by the vengeance of the Greeks.[127] According to the historian J. Laurent (Les origines médiévales de la question arménienne, 1920), this example reflects the general attitude of Armenians towards the empire, as they were not Hellenized like other peoples of the empire but retained their cultural and religious identity. According to the same author, the Armenians betrayed Byzantium in the face of the Seljuks' invasion, thus contributing to their success. However, English historian S. Runciman called this opinion “fantastic nonsense”.[128] It is known that it was because of the invasive policy of the Byzantine Empire that the Bagratid of Armenia was destroyed, which, in turn, contributed to a more unimpeded advance of the Seljuks towards Anatolia and the further seizure of Byzantium itself. In turn, the Armenian author of the mid-13th century, Vardan the Great, believed that the word “generous” in the language of the Greeks does not exist at all.[56]

Some researchers note, that medieval images of ethnic groups are never ideologically neutral and can be a tool for the formation of one or another given idea. Such historical “images” sometimes can transform historical reality.[129]

Cultural interactions

[edit]

The influence of Byzantine culture on the formation of Armenian medieval culture was very significant. This was most notably manifested in literature, where Armenian literature was influenced both directly by Byzantine and Syriac literature, which, in turn, was largely shaped by it. Theological literature and scientific works from all spheres of medieval knowledge were translated from Greek. Through many generations of translators from the so-called Hellenizing School, Armenian readers gained access not only to works of classical philosophical thought but also to original Armenian creations. According to N. Y. Marr, in the 7th and 8th centuries, the educated Armenian society was fascinated by philosophy. The Neoplatonist David the Invincible wrote and lectured in Greek.[131] Additionally, many borrowings from Greek were introduced into the Armenian language, which later entered the New Armenian language. Greek culture was primarily accessible to the clergy, but secular admirers of ancient culture in Armenia are also known, such as the 11th-century scholar Grigor Magistros.[132] At the same time, it is acknowledged that Armenian culture had an impact on Byzantine culture.[133] The well-known Armenologist R. M. Bartikyan notes a significant Armenian element in the Byzantine epic about Digenis Akritas, many of whose ancestors were of Armenian origin.[134]

In the field of silver production, the Byzantine influence on Armenian jewelry art was first brought to the attention of the 19th-century French Armenist A. Carrier. This idea was further developed in the works of G. Hovsepian, S. Der Nersessian, A. Kurdanyan, A. Khachatryan, and N. Stepanyan. Nevertheless, according to A. Y. Kakovkin, the majority of Armenian monuments of silverwork from the 11th to the 15th centuries, despite the presence of points of contact, exhibit a vivid originality and independence from Greek works.[135] In addition to jewelry art, Byzantine elements (for example, the Deesis motif)[136] entered other branches of fine arts in Armenia, particularly miniature painting.[137] The Byzantine influence becomes most noticeable in the miniatures of Cilician Armenia during the late 12th to early 13th centuries.[138]

In Armenian sculpture, the Byzantine influence is much less noticeable, as stone sculptures were not widespread in Byzantium, where brick buildings predominated. Der Nersessian believes that, conversely, one can find traces of Armenian sculpture's influence in Byzantium, especially in the monuments of Greece, Macedonia, and Thrace. The earliest examples are found in Boeotia, in the church of Gregory Nazianzus in Thebes from 872 and in the church of the Holy Virgin in Skripu from 874, where reliefs depict motifs of birds and animals enclosed in medallions, typical of Armenian sculptures.[139] Nevertheless, Byzantine motifs, such as ‘imperial eagles,’ can be found in the sculptures of Zvartnots.[140] The question of interrelations in the field of architecture is rather complicated. In the early 20th century, N. Y. Marr pointed out the influence of Byzantine Syria on Armenian architecture in the 5th and 6th centuries, using the example of the Yererouk basilica. Later, I. A. Orbeli stated that "the first architectural monuments (almost the only heritage of the oldest Christian art of Armenia) have a purely Syrian character”.[141]

A. L. Yakobson has repeatedly addressed the question of architectural influence, using the Jererui and Tekora basilicas as examples to illustrate the common features they share with Syrian buildings, such as the presence of towers on either side of the entrance and galleries with porticoes along the northern and southern sides of the temples.[142] This researcher also identifies elements of Syrian architecture in secular buildings, specifically the palaces in Dvina and Arucha.[143] In contrast, S. H. Mnatsakanyan argues for the potential influence of Armenian cross-in-square temples, which he attributes to the Echmiadzin monastery, on the development of Middle Byzantine cross-in-square architecture.[144] Byzantine features can also be observed in the Zvartnots temple, built in the early 640s during the Byzantine occupation of Armenia. However, as noted by American expert on Armenian architecture K. Maranzi, the specific characteristics of this similarity have not been thoroughly investigated.[145] Several researchers have pointed out that the resettlement of Armenians to the western regions of Byzantium left a significant mark on the architecture of the area. As early as 1899, Auguste Choisy highlighted the influence of Armenian architecture in the Balkans, particularly in Serbia.[146] The rose patterns found in Serbia, which are unique to the region, are sometimes attributed to connections with Armenian, Georgian, or Islamic architecture.[147] Contacts with Armenian architecture can be observed in the designs of churches such as Hagia Sophia, the Holy Virgin in Skripu, and in the brickwork of Pliska.[148] By the end of the 13th century, architectural traditions in the highland regions of Asia Minor underwent significant changes, likely influenced by Armenia or Georgia.[149] The French art historian Gabriel Millet pointed out that Greek architecture exhibited more inspiration from Anatolian and Armenian designs than from Constantinopolitan architecture, highlighting important differences between the churches of Greece and Constantinople.[146] Joseph Strzygowski argued that Byzantine architecture in the 11th century adopted several characteristic features of Armenian architecture, although his views remain controversial.[150] K. Toumanoff further notes that Armenian architects achieved international recognition during this period.[151] For example, one of the most renowned architects of his time, the Armenian architect Trdat, was responsible for the restoration of the dome of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, which had been damaged by an earthquake.[152] Later, he went on to construct the Ani Cathedral. Research conducted on the dome of Hagia Sophia revealed some unique structural solutions implemented by Trdat; however, there are no known examples of these techniques being applied in other Byzantine churches. Additionally, the Armenian buildings designed by Trdat did not exhibit significant features characteristic of Constantinopolitan architecture.[153]

References

[edit]- ^ Thomson W. (1997, p. 219)

- ^ Страбон, География Archive: 18 April 2015

- ^ Kurbatov (1967, p. 74)

- ^ a b Stratos (1980, p. 165)

- ^ Charanis (1961, p. 197)

- ^ Treadgold (1988, p. 92)

- ^ Procopius of Caesarea (1996, p. III.32.7)

- ^ Garsoïan (1998, p. 56)

- ^ Sebeos (1862, p. 52)

- ^ Charanis (1959, p. 30)

- ^ Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (1991, p. 227)

- ^ Charanis (1961, p. 212)

- ^ Charanis (1961, p. 199)

- ^ Taronetsi (1863, p. 146)

- ^ Charanis (1961, p. 200)

- ^ Stepanenko (1975, p. 127)

- ^ Charanis (1961, pp. 233–234)

- ^ Charanis (1961, p. 237)

- ^ Хронографическая история, составленная отцом Мехитаром, вардапетом Айриванкским / пер. К. Патканова [A chronographic history compiled by Father Mehitar, Vardapet of Ayrivanka] (in Russian). СПб. 1869.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) P. 407. - ^ Ayrarat — статья из Encyclopædia Iranica. R. H. Hewsen

- ^ Shaguinyan (2011, p. 67)

- ^ Shaguinyan (2011, pp. 72–84)

- ^ Shaguinyan (2011, p. 96)

- ^ Charanis (1961, pp. 214–216)

- ^ Bartikyan (2000)

- ^ a b См. Г. Г. Литаврин. Комментарий к главам 44—53 трактата «Об управлении империей». Комм. 2 к главе 44. Archive: 4 November 2011.

- ^ Uzbasyan (1971, pp. 38–39)

- ^ Uzbasyan (1971, p. 40)

- ^ Melikset-Beck (1961, p. 70)

- ^ Taronetsi (1863)

- ^ Melikset-Beck (1961)

- ^ Евагрий, Церковная история, V.19

- ^ Charanis (1965)

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium: in 3 vol. / ed. by Dr. Alexander Kazhdan. N. Y.; Oxf.: Oxford University Press. 1991. p. 1218. ISBN 0-19-504652-8

- ^ Феофилакт Симокатта, История, 3.III.1

- ^ Shahid (1972, p. 309)

- ^ Shahid (1972, pp. 310–311)

- ^ Kaegi (2003, pp. 21–22)

- ^ Martindale J. R. Heraclius 4 // Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. [2001 reprint]. Cambr.: Cambridge University Press, 1992. Vol. III (b): A.D. 527–641. P. 586. ISBN 0-521-20160-8

- ^ a b Toumanoff (1971, p. 135)

- ^ Продолжатель Феофана, Лев V, 1.

- ^ Продолжатель Феофана. Жизнеописания византийских царей / изд подготовил Любарский Я. Н. 2 изд. СПб.: «Алетейя», 2009. 400 p. (Византийская библиотека. Источники). ISBN 978-5-91419-146-4

- ^ Treadgold (1988, p. 196)

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium: in 3 vol. / ed. by Dr. Alexander Kazhdan. N. Y.; Oxf.: Oxford University Press. 1991. p. 1209. ISBN 0-19-504652-8

- ^ Bartikyan (1992, p. 84)

- ^ Ostrogorsky (2011, p. 289)

- ^ Charanis (1961, pp. 207–208)

- ^ Bartikyan (1992, p. 87)

- ^ Treadgold (1988, p. 197)

- ^ Vasiliev (1906, p. 149)

- ^ Vasiliev (1906, p. 154)

- ^ Vasiliev (1906, p. 158)

- ^ Vasiliev (1906, p. 159)

- ^ Vasiliev (1906, p. 160)

- ^ Vasiliev (1906, p. 164)

- ^ a b c Всеобщая история Вардана Великого / пер. Н. Эмина [General History of Vardan the Great] (in Russian). М. 1861.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Charanis (1961, p. 223)

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium: in 3 vol. / ed. by Dr. Alexander Kazhdan. N. Y.; Oxf.: Oxford University Press. 1991. p. 1262. ISBN 0-19-504652-8

- ^ Ostrogorsky (2011, p. 302)

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium: in 3 vol. / ed. by Dr. Alexander Kazhdan. N. Y.; Oxf.: Oxford University Press. 1991. p. 1806. ISBN 0-19-504652-8

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium: in 3 vol. / ed. by Dr. Alexander Kazhdan. N. Y.; Oxf.: Oxford University Press. 1991. p. 1045. ISBN 0-19-504652-8

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium: in 3 vol. / ed. by Dr. Alexander Kazhdan. N. Y.; Oxf.: Oxford University Press. 1991. p. 1666. ISBN 0-19-504652-8

- ^ Bartikyan (1992, p. 83)

- ^ Kazhdan (1975, pp. 5–7)

- ^ Kazhdan (1975, p. 147)

- ^ Garsoïan (1998, p. 65)

- ^ Kazhdan (1975, p. 145)

- ^ Garsoïan (1998, p. 88)

- ^ Kazhdan (1975, pp. 10–11)

- ^ Продолжатель Феофана, Жизнь Василия, 12

- ^ Charanis (1961, p. 209)

- ^ Charanis (1961, pp. 229–230)

- ^ George A. Kennedy. A New History of Classical Rhetoric. Princeton University Press, 1994. P. 244. ISBN 978-0-69100-059-6

- ^ Lemerl (2012, pp. 117–121)

- ^ Lemerl (2012, p. 138)

- ^ a b c Trkulja J., Lees C.

- ^ Adontz (1950, pp. 65–66)

- ^ a b Charanis (1961, p. 211)

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium: in 3 vol. / ed. by Dr. Alexander Kazhdan. N. Y.; Oxf.: Oxford University Press. 1991. p. 1969. ISBN 0-19-504652-8

- ^ Adontz (1950, pp. 57–58)

- ^ Adontz (1950, pp. 57–61)

- ^ Treadgold, Warren (2013). The Middle Byzantine Historians. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 181. ISBN 978-1-13728-085-5.

- ^ Charanis (1961, p. 221)

- ^ Winkelmann F., Lilie R.-J., Ludwig C., Pratsch T., Rochow I. Konstantinos Maniakes (# 3962) // Prosopographie der mittelbyzantinischen Zeit: I. Abteilung (641–867), 2. Band: Georgios (# 2183). Leon (# 4270). Walter de Gruyter, 2000. P. 577–579. ISBN 978-3-11016-672-9

- ^ Kazhdan (1975, pp. 28–33)

- ^ Adontz (1950, p. 72)

- ^ Garsoïan (1998, p. 64)

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium: in 3 vol. / ed. by Dr. Alexander Kazhdan. N. Y.; Oxf.: Oxford University Press. 1991. p. 1438. ISBN 0-19-504652-8

- ^ Charanis (1959, p. 31)

- ^ Balard M., Ducellier A. (2002, p. 34)

- ^ Charanis (1959, p. 32)

- ^ Sebeos (1862, p. 57)

- ^ Sebeos (1862, pp. 59–60)

- ^ a b c Charanis (1959, p. 33)

- ^ Mokhov (2013, p. 127)

- ^ Феофан, Хронография, л.м. 6160

- ^ Shaguinyan (2011, p. 114)

- ^ Charanis (1959, pp. 34–35)

- ^ Charanis (1961, p. 208)

- ^ Dédéyan (1993, p. 69)

- ^ Charanis (1961, p. 213)

- ^ Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (1991, p. 229)

- ^ Mokhov (2013, p. 120)

- ^ Mokhov (2013, p. 77)

- ^ Mokhov (2013, p. 144)

- ^ Mokhov (2013, p. 149)

- ^ Charanis (1961, pp. 204–205)

- ^ Аноним (Перевод: Д. Попов). О сшибках с неприятелями сочинение государя Никифора. История Льва Диакона Калойского и другие сочинения византийских писателей. СПб.: Типография ИАН, 1820, стр. 113-163. Дата обращения: 24 April 2015.

- ^ Charanis (1961, p. 217)

- ^ Vryonis (1959, p. 172)

- ^ Charanis (1961, p. 235)

- ^ Армения // Энциклопедия Кольера. Открытое общество, 2000.

- ^ Garsoïan (1998, p. 68)

- ^ Arutyunova-Fidanyan (2012, p. 10)

- ^ Uzbasyan (1971, p. 42)

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium: in 3 vol. / ed. by Dr. Alexander Kazhdan. N. Y.; Oxf.: Oxford University Press. 1991. p. 210. ISBN 0-19-504652-8

- ^ Arutyunova-Fidanyan (2010, p. 30)

- ^ Анания Мокаци // Православная энциклопедия. М., 2000. V. 2. P. 223.

- ^ Vryonis (1959, pp. 170–171)

- ^ Всеобщая история Вардана Великого / пер. Н. Эмина [General History of Vardan the Great] (in Russian). М. 1861.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) P. 157. - ^ Uzbasyan (1971, p. 41)

- ^ Rosser (2011, p. 33)

- ^ Vryonis (1959, p. 173)

- ^ Senina (2012, p. 122)

- ^ Лев Диакон, История, book IV, 7.

- ^ Garsoïan (1998, p. 59)

- ^ Виллардуэн, Завоевание Константинополя, 385.

- ^ Charanis (1961, pp. 237–239)

- ^ Arutyunova-Fidanyan (1991, p. 113)

- ^ Makris E. Греция. Часть II: Архитектура // Православная энциклопедия. М., 2006. V. XII : Гомельская и Жлобинская епархия — Григорий Пакуриан. pp. 391—427. ISBN 5-89572-017-X

- ^ Arutyunova-Fidanyan (2012, p. 15)

- ^ Uzbasyan (1971, p. 44)

- ^ Udaltsova (1967)

- ^ Bartikian H. Armenia and Armenians in the Byzantine Epic // ed. R. Beaton, D. Ricks Digenis Akrites. New Approaches to Byzantine Heroic Poetry. Variorum, 1993. pp. 86—92. ISBN 0-86078-395-2

- ^ Kakovkin (1973)

- ^ Der Nersessian (1945, pp. 97–98)

- ^ Der Nersessian (1945)

- ^ Der Nersessian (1945, pp. 122–127)

- ^ Der Nersessian (1945, p. 108)

- ^ a b Maranci (2001, p. 113)

- ^ Yakobson (1976, pp. 192–193)

- ^ Yakobson (1976, p. 196)

- ^ Yakobson (1976, p. 196)

- ^ Mnazakanyan (1985)

- ^ Maranci (2001, p. 106)

- ^ a b Der Nersessian (1945, p. 56)

- ^ Johnson M. J., Ousterhout R. G., Papalexandrou A. (2012, p. 145)

- ^ Krautheimer R., Curcic S. (1992, p. 316)

- ^ Krautheimer R., Curcic S. (1992, p. 420)

- ^ Der Nersessian (1945, pp. 75–78)

- ^ Cyril Toumanoff. Armenia and Georgia // The Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge, 1966. V. IV: The Byzantine Empire, part I, chapter XIV. pp. 593—637.

- ^ Асолик, Всеобщая история, book III, XXVII.

- ^ Maranci (2003)

Bibliography

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Draskhanakerttsi, Hovhannes (1984). История Армении [History of Armenia] (in Russian). Ер.: Издательство АН АрмССР.

- Taronetsi, Stepanos (1863). Всеобщая история Степаноса Таронского, Асохика по прозванию, писателя XI столетия / перевод Н.Эмина. — [Stepanos Taronetsi's Universal History] (in Russian). М.: Типогр. Лазарев. Инст. восточ. языков.

- Lastivertsi, Aristakes (1968). Повествование вардапета Аристакэса Ластиверци [Aristakes Lastivertsi vardapet's Narrative] (in Russian). Vol. 15. Памятники пис'менности востока. М.: «Наука», Главная ред. восточной литературы. p. 194.

- Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (1991). Об управлении империей / Под редакцией Г. Г. Литаврина и А. П. Новосельцева [On the Empire's Governance] (in Russian). М.: Наука. p. 496. ISBN 5-02-008637-1

- Theophanes Continuatus (2009). Жизнеописания византийских царей / изд подготовил Любарский Я. Н.. — 2 изд [Biographies of Byzantine emperors]. Византийская библиотека. Источники (in Russian). СПб.: «Алетейя». p. 400. ISBN 978-5-91419-146-4.

- Procopius of Caesarea (1996). Война с готами [The War with the Goths] (in Russian). М.: Арктос. p. 167. ISBN 5-85551-143-X

- Sebeos (1862). История императора Иракла [History of Heraclius] (in Russian). СПб. p. 216.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Theophanes the Confessor (1884). Летопись византийца Феофана от Диоклетиана до царей Михаила и сына его Феофилакта [Annals of the Byzantine Theophanes from Diocletian to the kings Michael and his son Theophylact] (in Russian). М.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Theophylact Simocatta (1957). История / Перевод С. П. Кондратьева [History] (in Russian). Изд-во АН СССР. p. 222.

- Всеобщая история Вардана Великого / пер. Н. Эмина [General History of Vardan the Great] (in Russian). М. 1861.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Хронографическая история, составленная отцом Мехитаром, вардапетом Айриванкским / пер. К. Патканова [A chronographic history compiled by Father Mehitar, Vardapet of Ayrivanka] (in Russian). СПб. 1869.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Researches

[edit]In English

[edit]- Adontz, N. (1950). Role of the Armenians in Byzantine Science // Armenian Review. Vol. 3. Boston: Hairenik Association. pp. 55–73.

- Charanis, P. (1959). Ethnic Changes in the Byzantine Empire in the Seventh Century // Dumbarton Oaks Papers. Vol. 13. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 23–44. doi:10.2307/1291127. ISSN 0070-7546. JSTOR 1291127.

- Charanis, P. (1961). The Armenians in the Byzantine Empire // Byzantinoslavica. pp. 196–240.

- Charanis, P. (1965). A Note on the Ethnic Origin of the Emperor Maurice // Byzantion. Vol. XXXV. pp. 412–417.

- Der Nersessian, S. (1945). Armenia and the Byzantine Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 148.

- Garsoïan, N. (1998). The Problem of Armenian Integration into the Byzantine Empire // Hélène Ahrweiler, Angeliki E. Laiou. Studies on the Internal Diaspora of the Byzantine Empire. Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 53–124. ISBN 978-0-88402-247-3. ISBN 0-88402-247-1

- Johnson M. J., Ousterhout R. G., Papalexandrou A. (2012). Approaches to Byzantine Architecture and Its Decoration. Farham: Ashgate Publishing. p. 309. ISBN 978-1-4094-2740-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kaegi, W. (2003). Heraclius Emperor of Byzance. Cambr: Cambridge University Press. p. 359. ISBN 0 521 81459 6

- The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium: in 3 vol. / ed. by Dr. Alexander Kazhdan. N. Y.; Oxf.: Oxford University Press. 1991. p. 2232. ISBN 0-19-504652-8

- Krautheimer R., Curcic S. (1992). Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture. New Heaven: Yale University Press. p. 553. ISBN 978-0-3000-5294-7.

- Maranci, Ch. (2001). Byzantium through Armenian Eyes: Cultural Appropriation and the Church of Zuart'noc' // Gesta. Vol. 40. pp. 105–124.

- Maranci, Ch. (2003). The Architect Trdat: Building Practices and Cross-Cultural Exchange in Byzantium and Armenia // Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. Vol. 62. Chicago: University of California Press. pp. 294–305. JSTOR 767241.

- Rosser, J. H. (2011). Historical Dictionary of Byzantium. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press.

- Shahid, I. (1972). The Iranian Factor in Byzantium during the Reign of Heraclius // Dumbarton Oaks Papers. Vol. 26. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 293–320. JSTOR 1291324.

- Stratos, A. (1980). Byzantium in the Seventh Century. Amsterdam: Cambridge University Press. p. 203. ISBN 90-256-0852-3

- Toumanoff, C. (1971). Caucasia and Byzantium // Traditio. Cambr.: Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–158.

- Treadgold, Warren (1988). The Byzantine Revival, 780–842 / American Council of Learned Societies. ACLS Humanities E-Book. Vol. XV. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-804-71462-4.

- Trkulja J., Lees C. Armenians in Constantinople. Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Κωνσταντινούπολη (28 February 2008).

- Vryonis, S. (1959). "Byzantium: The Social Basis of Decline in the Eleventh Century // GRBS". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 2 (2). Durham, NC: Duke University Press: 159–175.

- Thomson W., Robert (1997). Armenian Literary Culture through the Eleventh Century // The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century / edited by Richard G. Hovannisian. Vol. I. N. Y.: St. Martin’s Press. pp. 199–241.

In Russian

[edit]- Adonts, N. G. (1971). Армения в эпоху Юстиниана [Armenia in the Age of Justinian] (in Russian). Ер.: Изд-во Ереванского Университета. p. 526. Archived from the original on 2018-06-21.

- Arutyunova-Fidanyan, V. A. (2010). Полемика между халкидонитами и монофизитами и переписка патриарха Фотия [Polemics between Chalcedonites and Monophysites and the correspondence of Patriarch Photius] (PDF) (in Russian). Vol. I: Богословие. Вестник ПСТГУ. pp. 23–33.

- Arutyunova-Fidanyan, V. A. (2012). Армяно-халкидонитскаяя аристократия на службе империи: полководцы и дипломатические агенты Константина VII Багрянородного [The Armenian-Chalcedonian Aristocracy in the Service of the Empire: Commanders and Diplomatic Agents of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus] (PDF) (in Russian). Vol. III: Филология. Вестник ПСТГУ. pp. 7–17.

- Arutyunova-Fidanyan, V. A. (1991). Образ Византии в армянской средневековой историографии X в. Византийский временник [The image of Byzantium in Armenian medieval historiography of the 10th century] (in Russian). Vol. 52 (77). М.: «Наука».

- Bartikyan, R. M. (1992). Неизвестная армянская аристократическая фамилия на службе в Византии в IX-XI вв // Античная древность и средние века [Unknown Armenian aristocratic surname in the service of Byzantium in IX-XI centuries // Antiquity and Middle Ages] (PDF) (in Russian). Барнаул: Уральский федеральный университет. pp. 83–91.

- Bartikyan, R. M. (2000). О царском кураторе "MANZHKEPT KAI EΣΩ IBHPIAΣ" Михаиле. В связи с восточной политикой Василия II (976— 1025 гг.) // Историко-филологический журнал [About the royal curator “MANZHKEPT KAI EΣΩ IBHPIAΣ” Michael. In connection with the eastern policy of Basil II (976- 1025)] (PDF) (in Russian). Ер.: Изд-во НАН РА.

- Vasiliev, A. A. (1906). Происхожденіе императора Василія Македонянина [The origin of Emperor Basil the Great] (in Russian). Vol. XII. Византийский временник. pp. 148–165.

- Kakovkin, A.Ya. (1973). К вопросу о византийском влиянии на армянские памятники художественного серебра [On the question of Byzantine influence on Armenian art silver monuments] (in Russian). Պատմա-Բանասիրական Հանդես. pp. 49–60.

- Kazhdan, A. P. (1975). Армяне в составе господствующего класса Византийской империи в XI—XII вв [Armenians in the ruling class of the Byzantine Empire in the XI-XII centuries.] (in Russian). Ер.: Изд-во АН Армянской ССР. p. 190.

- Kulakovsky, Yu. A. (1996). История Византии [History of Byzantium] (in Russian). Vol. III. СПб.: «Алетейя». p. 454.

- Kurbatov, G. L. (1967). Образование Византии. Территория природные условия и население // Отв. редактор С. Д. Сказкин История Византии [Formation of Byzantium. Territory, natural conditions and population] (in Russian). Vol. I. Наука. pp. 66–75.

- Lemerl, P. (2012). Первый византийский гуманизм [First Byzantine Humanism] (in Russian). СПб.: Своё издательство. p. 490. ISBN 9785-4386-5145-1.

- Melikset-Beck, L. M. (1961). Из истории армяно-византийских отношений // Византийский временник [From the History of Armenian-Byzantine Relations // Byzantium Times] (in Russian). Vol. 20. М.: «Наука». pp. 64–74.

- Mnazakanyan, S. (1985). Архитектура Армении в контексте зодчества Переднего Востока (по поводу последних трудов А. Л. Якобсона) // Պատմա-Բանասիրական Հանդես [Architecture of Armenia in the context of architecture of the Near East (on the recent works of A. L. Yakobson) // Պատմա-Բանասիրական Հանդես] (in Russian). pp. 66–74. ISSN 0320-8117.

- Mokhov, A. S. (2013). Византийская армия в середине VIII — середине XI в.: Развитие военно-административных структур [Byzantine army in the middle of the VIIIth to the middle of the XIth century: Development of military-administrative structures] (PDF) (in Russian). Екатеринбург: Издательство Уральского университета. p. 278. ISBN 978-5-7996-1035-7.

- Ostrogorsky, G. A. (2011). История Византийского государства / Пер. с нем.: М. В. Грацианский. Ред. П. В. Кузенков [History of the Byzantine state] (in Russian). М.: Сибирская Благозвонница. p. 895. ISBN 978-5-91362-458-1.

- Senina, T. A. (nun Cassia) (2012). «Лев Преступник». Царствование византийского императора Льва V Армянина в отражении византийских хронистов IX века [“Leo the Criminal. The reign of the Byzantine Emperor Leo V the Armenian in the reflection of Byzantine chroniclers of the IX century] (in Russian). М.: Accent Graphics Communications. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-927480-41-0.

- Stepanenko, V. S. (1975). Политическая обстановка в Закавказье в первой половине XI в // Античная древность и средние века [Political situation in Transcaucasia in the first half of the 11th century // Antiquity and Middle Ages] (PDF) (in Russian). Свердловск: Уральский государственный университет. pp. 124–132.

- Stepanenko, V. S. (1999). Армяне-халкидониты в истории Византии XI в.: (По поводу книги В. А. Арутюновой-Фиданян) // Византийский временник [Chalcedonite Armenians in the history of Byzantium in the XI century: (On the book by V. A. Arutyunova-Fidanyan) // Byzantine Temporal Book] (PDF) (in Russian). Vol. 59. М.: Наука. pp. 40–61.

- Udaltsova, Z. V. (1967). Своеобразие общественного развития Византийской империи. Место Византии во всемирной истории // Отв. редактор С. Д. Сказкин История Византии [The peculiarity of social development of the Byzantine Empire. The place of Byzantium in world history] (in Russian). Vol. III. «Наука». pp. 303–341.

- Shaguinyan, A. K. (2011). Армения и страны Южного Кавказа в условиях византийско-иранской и арабской власти [Armenia and the South Caucasus countries under Byzantine-Iranian and Arab rule] (in Russian). СПб.: «Алетейя». p. 512. ISBN 978-5-914195-73-8.

- Uzbasyan, K. N. (1971). Некоторые проблемы изучения армяно-византийских отношений // Լրաբեր Հասարակական Գիտությունների [Some problems of studying Armenian-Byzantine relations // Լրաբեր Հասարակական Գիտություների] (in Russian). Ер. pp. 36–45.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Yakobson, A. L. (1976). Армения и Сирия: Архитектурные сопоставления // Византийский временник [Armenia and Syria: Architectural Comparisons // Byzantine Temporal Book] (in Russian). Vol. 37. М.: Наука. pp. 192–206.

In French

[edit]- Dédéyan, G. (1993). "Les Arméniens sur la frontière sud-orientale de Byzance, fin IXe - fin XIe siècle // La Frontière. Séminaire de recherche sous la direction d'Yves Roman" [Armenians on the south-eastern frontier of Byzantium, late 9th - late 11th century]. Mom Éditions (in French). 21 (1). Lyon: Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée Jean Pouilloux: 67–85.

- Dorfmann-Lazarev, I. (2004). Arméniens et byzantins à l'époque de Photius: deux débats théologiques après le triomphe de l'orthodoxie [Armenians and Byzantines at the time of Photius: two theological debates after the triumph of Orthodoxy] (in French). Leuven: Peeters. p. 321.

- Goubert, P. (1941). "Maurice et l'Arménie [Note sur le lieu d'origine et la famille de l'empereur Maurice (582-602)] // Échos d'Orient" [Maurice and Armenia [Note on the place of origin and family of Emperor Maurice (582-602)]]. Revue des Études Byzantines (in French). 39 (199–200). P.: Institut français d'études byzantines: 383–413. doi:10.3406/rebyz.1941.2971.

- Balard M., Ducellier A. (2002). Les Arméniens en Italie byzantine (VIe–XIe siècle) // Migrations et diasporas méditerranéennes: Xe-XVIe siècles [The Armenians in Byzantine Italy (6th-11th centuries) // Mediterranean migrations and diasporas: 10th-16th centuries] (in French). Vol. 19. P.: Publications de la Sorbonne. pp. 33–37. ISBN 978-2-85944-448-8.