American Idiot

| American Idiot | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | September 21, 2004 | |||

| Studio | ||||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 57:14 | |||

| Label | Reprise | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| Green Day chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from American Idiot | ||||

| ||||

American Idiot is the seventh studio album by the American rock band Green Day, released on September 21, 2004, by Reprise Records. As with their previous four albums, it was produced by Rob Cavallo in collaboration with the group. Recording sessions for American Idiot took place at Studio 880 in Oakland and Ocean Way Recording in Hollywood, both in California, between 2003 and 2004. A concept album, dubbed a "punk rock opera" by the band members, American Idiot follows the story of Jesus of Suburbia, a lower-middle-class American adolescent anti-hero. The album expresses the disillusionment and dissent of a generation that came of age in a period shaped by tumultuous events such as 9/11 and the Iraq War. In order to accomplish this, the band used unconventional techniques for themselves, including transitions between connected songs and some long, chaptered, creative compositions presenting the album themes.

Following the disappointing sales of their previous album Warning (2000), the band took a break and then began what they had planned to be their next album, Cigarettes and Valentines. However, recording was cut short when the master tapes were stolen; meaning that all copies of the songs were lost. following this, the band made the decision to start their next album from scratch. The result was a more societal critical, politically charged record which returned to the band's punk rock sound following the more folk and power pop-inspired Warning, with additional influences that were not explored on their older albums. Additionally, the band underwent an "image change", wearing red and black uniforms onstage, to add more theatrical presence to the album during performances and press events.

American Idiot became one of the most anticipated releases of 2004. It marked a career comeback for Green Day, charting in 27 countries, reaching for the first time the top spot on the Billboard 200 for the group and peaking at number one in 18 other countries. It has sold over 16 million copies worldwide, making it the second best-selling album for the band (behind their 1994 major-label debut, Dookie) and one of the best-selling albums of the decade. It was later certified 6× Platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America in 2013. The album spawned five successful singles: the titular track, "American Idiot", "Holiday", "Wake Me Up When September Ends", "Jesus of Suburbia" and the Grammy Award for Record of the Year winner "Boulevard of Broken Dreams".

American Idiot was very well received critically and commercially upon release, and has since been hailed as one of the greatest albums of all time. It was nominated for Album of the Year and won the Award for Best Rock Album at the 2005 Grammy Awards. It was also nominated for Best Album at the Europe Music Awards and the Billboard Music Awards, winning the former. Its success inspired a Broadway musical, a documentary and a planned feature film adaptation. Rolling Stone placed it at 225 on their 2012 list of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time", and again in 2020, at 248.

Background[edit]

Green Day was one of the most popular rock acts of the 90s.[1] However, their 2000 album Warning was a commercial disappointment[2] despite largely positive reviews.[3] In early 2002, they embarked on the Pop Disaster Tour, headlining with Blink-182.[4] The tour created momentum for the band, who were earning a reputation as "elder statesmen" of the pop punk scene, which consisted of bands like Good Charlotte, Sum 41, and New Found Glory.[5][6]

Things had come to a point regarding unresolved personal issues between the three band members. The band was argumentative and miserable, according to the bassist Mike Dirnt, and needed to "shift directions".[7] In addition, the band released a greatest hits album, International Superhits!, which they felt was "an invitation to midlife crisis".[8] The singer Billie Joe Armstrong called Dirnt and asked him, "Do you wanna do [the band] anymore?" He felt insecure, having become "fascinated and horrified" by his reckless lifestyle, and his marriage was in jeopardy.[9] Dirnt and Tré Cool viewed the singer as controlling, while Armstrong feared to show his bandmates new songs.[7] Beginning in January 2003, the group had weekly personal discussions, which resulted in a revitalized feeling among the musicians.[10][11] They settled on more musical input from Cool and Dirnt, with "more respect and less criticism".[9]

Green Day had spent much of 2002 recording new material at Studio 880 in Oakland, California for an album titled Cigarettes and Valentines,[12] creating "polka songs, filthy versions of Christmas tunes, [and] salsa numbers" for the project, hoping to establish something new within their music.[7] After completing 20 songs, the demo master tapes were stolen that November.[13] In 2016, Armstrong and Dirnt said that they eventually recovered the material and were using it for ideas.[14]

After the theft, the band consulted longtime producer Rob Cavallo. Cavallo told them to ask themselves if the missing tracks represented their best work.[15] Armstrong said that they "couldn't honestly look at ourselves and say, 'That was the best thing we've ever done.' So we decided to move on and do something completely new."[16][5] They agreed and spent the next three months writing new material.[17]

Recording and production[edit]

The members of Green Day individually crafted their own ambitious 30-second songs. Armstrong recalled, "It started getting more serious as we tried to outdo one another. We kept connecting these little half-minute bits until we had something." This musical suite became "Homecoming", and the band wrote another suite, "Jesus of Suburbia".[5] It changed the development of the album, and the band began viewing songs as more than their format—as chapters, movements, or potentially a feature film or novel.[6] Soon afterward, Armstrong penned the title track, which explicitly addresses sociopolitical issues. The group then decided that they would steer the development of the album toward what they dubbed a "punk rock opera."[18]

Prior to recording, Green Day rented rehearsal space in Oakland, once again at Studio 880. Armstrong invited Cavallo to attend the sessions and help guide their writing processes. Cavallo encouraged the idea of a concept album, recalling a conversation the two had a decade prior, in which Armstrong expressed his desire for their career to have a "Beatles-like arc to their creativity."[18] During the sessions at Studio 880, Green Day spent their days writing material and would stay up late, drinking and discussing music. The band set up a pirate radio station from which it would broadcast jam sessions, along with occasional prank calls.[16] The band demoed the album sufficiently so that it would be completely written and sequenced before they went to record.[19]

Hoping to clear his head and develop new ideas for songs, Armstrong traveled to New York City alone for a few weeks, renting a small loft in the East Village of Manhattan.[20] He spent much of this time taking long walks and participating in jam sessions in the basement of Hi-Fi, a bar in Manhattan.[21] He began socializing with the songwriters Ryan Adams and Jesse Malin.[22] Many songs from the album were written based on his time in Manhattan, including "Boulevard of Broken Dreams" and "Are We the Waiting". While there, he also formulated much of the album's storyline, about people "going away and getting the hell out, while at the same time fighting their own inner demons."[22]

With demos completed, Green Day relocated to Los Angeles.[23] They first recorded at Ocean Way Recording, then moved to Capitol Studios to complete the album.[24] Cool brought multiple drum kits, including over 75 snares.[25] Drum tracks were recorded on two-inch tape to produce a compressed sound and were transferred to Pro Tools to be digitally mixed with the other instruments.[24][26] All drum tracks were produced at Ocean Way Studio B, picked for its high ceiling and acoustic tiling, which produced better sound.[26] The songs were recorded in order as they appear on the track listing, a first for Green Day.[27] Each song was recorded in its entirety before proceeding to the next.[28] They reversed the order in which they recorded guitars and bass (recording the guitars first), as they heard that was how the Beatles recorded songs.[26] Armstrong said that at points he expressed fear at the amount of work before him, likening it to climbing a mountain.[6]

The band took a relaxed approach to recording. For five months, they stayed at a Hollywood hotel during the recording sessions, where they would often play loud music late at night, prompting complaints.[29] The band admitted to partying during the L.A. sessions; Armstrong had to schedule vocal recording sessions around his hangovers. Armstrong described the environment: "For the first time, we separated from our pasts, from how we were supposed to behave as Green Day. For the first time, we fully accepted the fact that we're rock stars."[30] American Idiot took 10 months to complete, at a cost of $650,000.[22] By the end of the process, Armstrong felt "delirious" regarding the album: "I feel like I'm on the cusp of something with this. [...] I really feel […] like we're really peaking right now."[31]

Themes[edit]

"Everybody just sorta feels like they don't know where their future is heading right now, ya know?"

—Armstrong, October 2004[32]

American Idiot was inspired by contemporary American political events, particularly 9/11, the Iraq War, and the presidency of George W. Bush. There are only two overtly political songs on the album ("American Idiot" and "Holiday"),[33] but the album "draws a casual connection between contemporary American social dysfunction […] and the Bush ascendancy."[34] While the content is clearly of the times, Armstrong hoped it would remain timeless and become more an overarching statement on confusion.[35]

Armstrong expressed dismay at the then-upcoming presidential election.[32] He felt confused by the country's culture war, noting the particular division among the general public on the Iraq War. Summing up his feelings in an interview at the time, he said, "This war that's going on in Iraq [is] basically to build a pipeline and put up a fucking Wal-Mart."[32] Armstrong felt a duty to keep his sons away from violent images, including video games and news coverage of the war in Iraq and the 9/11 attacks.[32] Armstrong noted divisions between America's "television culture" (which he said only cared about cable news) versus the world's view of America, which could be considered as careless warmongers.[19] Dirnt felt similarly, especially so after viewing the 2004 documentary Fahrenheit 9/11. "You don't have to analyze every bit of information in order to know that something's not fucking right, and it's time to make a change."[18] Cool hoped the record would influence young people to vote Bush out, or, as he put it, "make the world a little more sane."[10] He had previously felt that it was not his place to "preach" to kids, but felt there was so much "on the line" in the 2004 election that he must.[27]

The album also takes aim at giant corporations putting small companies out of business. Cool made an example out of record shops closing when a national retailer makes it to town. "It's like there's just one voice you can hear," he said. "Not to sound like a preachy person, but it's getting towards the Big Brother of George Orwell's 1984— except here you have two or three corporations running everything."[19]

Composition[edit]

Music[edit]

Speaking on the album's musical content, Armstrong remarked, "For us, American Idiot is about taking those classic rock and roll elements, kicking out the rules, putting more ambition in, and making it current."[34] Part of recording the album was attempting to expand their familiar punk rock sound by experimenting with different styles such as new wave, Latin, and polka music.[36] The band listened to various rock operas, including the Who's Tommy (1969) and David Bowie's The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972).[5] Armstrong was particularly inspired by the Who's Quadrophenia, finding more in common with its "power chord mod-pop aesthetic" than other concept records, such as The Wall by Pink Floyd.[34] In addition, they listened to the cast recordings of Broadway musicals West Side Story, The Rocky Horror Show, Grease, and Jesus Christ Superstar,[34] and they let contemporary music influence them, including the rappers Eminem and Kanye West, as well as the rock band Linkin Park.[11] Armstrong considered rock music a "conservative" business with regard to the rigidity in which a band must release a single, create a music video, or head out on tour. He felt groups like the hip hop duo OutKast were "kicking rock's ass, because there's so much ambition."[16]

The band used more loud guitar sounds for the record. Armstrong said "We were like, 'Let's just go balls-out on the guitar sound—plug in the Les Pauls and Marshalls and let it rip'".[37] Armstrong added tracks of acoustic guitar-playing throughout the record to augment his electric guitar rhythms and Cool's drumming.[24]

For most of the record, Dirnt used an Ampeg SVT bass amplifier, recording with his signature Fender Precision Bass.[38] For the album, he and Cavallo strived for a "solid, big, thunderous" bass sound as opposed to one centered on countermelodies. Dirnt ran his bass guitar through an Evil Twin direct box, a staple of his recording methods since Dookie.[38] Cool also employs unorthodox instruments for punk music—timpani, glockenspiel, and hammer bells—which he received out of a promotional deal with Ludwig.[28] These instruments are especially evident on "Homecoming" and on "Wake Me Up When September Ends", the latter of which includes an African bead gourd that was welded to a remote hi-hat pedal for future live performances.[28] "Extraordinary Girl", originally titled "Radio Baghdad", features tablas in the intro performed by Cool.[39] For "Whatsername", Cool recorded drums in a room designed to record guitars to achieve a dry sound.[25] With all these techniques and influences considered, critics have called the album pop-punk[40][41] and alternative rock,[42][43] but primarily the aforementioned punk rock.[19][44][45][46][47]

Lyrics[edit]

American Idiot is a concept album that describes the story of a central character named Jesus of Suburbia, an anti-hero created by Billie Joe Armstrong.[34] It is written from the perspective of a lower-middle-class suburban American teen, raised on a diet of "soda pop and Ritalin."[34] Jesus of Suburbia hates his hometown and those close to him, so he leaves for the city.[48] The second character introduced in the story is St. Jimmy, a "swaggering punk rock freedom fighter par excellence."[49] Whatsername, "a 'Mother Revolution' figure," is introduced as a nemesis of St. Jimmy in the song "She's a Rebel".[49] The album's story is largely indeterminate, because the group was unsure of where to lead the plot's third quarter. In this sense, Armstrong decided to leave the ending up to the listeners' imagination.[24] The two secondary characters exemplify the record's main theme—"rage versus love"—in that while St. Jimmy is driven by "rebellion and self-destruction," Whatsername is focused on "following your beliefs and ethics."[24] Jesus of Suburbia eventually decides to follow the latter, resulting in the figurative suicide of St. Jimmy, which is revealed to be a facet of his personality.[24] In the album's final song, Jesus of Suburbia loses his connection with Whatsername as well, to the point in which he can't even remember her name.[24]

Through the story, Armstrong hoped to detail coming of age in America at the time of the album's release.[50] While he considered their previous record heartfelt, he felt a more instinctual feeling to speak for the time period in which the album was released.[32] He had felt the desire to increase the amount of political content in his lyricism as he grew into adulthood, noting that the "climate" surrounding his aging produced feelings of responsibility in the songs he wrote.[51] Armstrong said, "As soon as you abandon the verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge song structure ... it opens up your mind to this different way of writing, where there really are no rules."[34] In addition to the album's political content, it also touches on interpersonal relationships and what Dirnt labeled "confusion and loss of individuality."[19]

"American Idiot" contends that mass media has orchestrated paranoia and idiocy among the public, particularly cable news, which Armstrong felt had crossed the line from journalism to reality television, only showcasing violent footage intercut with advertisements.[37] The song emphasizes strong language, juxtaposing the words "faggot" and "America" to create what he imagined would be a voice for the disenfranchised.[31] "Holiday" took two months to finish writing, because Armstrong continually felt his lyrics were not good enough. Encouraged by Cavallo, he completed the song.[6] He later characterized the song as an outspoken "fuck you" to Bush.[5] "Give Me Novacaine" touches on American reality television of that time, which Armstrong likened to "gladiators in the coliseum."[31] "She's a Rebel" was inspired by Bikini Kill's "Rebel Girl".[49]

Artwork[edit]

After finishing the music for the album, the band decided that the artwork needed to reflect the themes on the record, likening the change of image to a political campaign. Armstrong recalled, "We wanted to be firing on all cylinders. Everything from the aesthetic to the music to the look. Just everything."[32] Green Day drew inspiration from Chinese communist propaganda art the band saw in art galleries on Melrose Avenue and recruited artist Chris Bilheimer, who had designed the art for the previous records Nimrod and International Superhits! to create the cover. The band aimed for the cover to be "at once uniform and powerful".[32] The album's artwork—"a Posada-stark print of a heart-shaped hand grenade gripped in a blood-soaked fist"—is representative of its political content.[32] After listening to the new music on his computer, Bilheimer took note of the lyric "And she's holding on my heart like a hand grenade" from "She's a Rebel". Influenced by artist Saul Bass's poster for the 1955 drama film The Man with the Golden Arm, Bilheimer created an upstretched arm holding a red heart-shaped grenade. Although he felt that red is the "most overused color in graphic design", he felt that the "immediate" qualities of the color deemed it appropriate for use on the cover. He explained, "I'm sure there's psychological theories of it being the same color of blood and therefore has the powers of life and death... And as a designer I always feel it's kind of a cop-out, so I never used it before. But there was no way you couldn't use it on this cover."[52]

Critical reception[edit]

| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 79/100[53] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Entertainment Weekly | B+[55] |

| The Guardian | |

| Mojo | |

| NME | 8/10[58] |

| Pitchfork | 7.2/10[59] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| USA Today | |

| The Village Voice | C+[63] |

American Idiot received critical acclaim from music critics. At Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream publications, the album received an average score of 79, based on 26 reviews.[53] According to AllMusic, it earned Green Day "easily the best reviewed album of their career."[1] The website's editor Stephen Thomas Erlewine praised the album as either "a collection of great songs" or as a whole, writing that, "in its musical muscle and sweeping, politically charged narrative, it's something of a masterpiece".[54] Pitchfork deemed it "ambitious" and successful in getting across its message, while "keep[ing] its mood and method deliberately, tenaciously, and angrily on point".[59] NME characterized it as "an onslaught of varied and marvellously good tunes presented in an unexpectedly inventive way."[58] Q called the album "a powerful work, noble in both intent and execution."[60] The New York Times commended Green Day for trumping "any pretension with melody and sheer fervor".[64] Chicago Sun-Times critic Jim DeRogatis wrote that the band had successfully "hit upon an actual 'adult' style of pop punk",[40] while USA Today's Edna Gundersen wrote that they had steered away from the "cartoonish" qualities of their previous work in favor of more mature, politically oriented themes.[62]

Entertainment Weekly said that despite being based on a musical theater concept "that periodically makes no sense", Green Day "makes the journey entertaining enough". It described some of the songs as forgettable, though, arguing the album focuses more on lyrics than music.[55] Rolling Stone said the album could have been, and was, a mess, but that the "individual tunes are tough and punchy enough to work on their own".[61] The Guardian also called American Idiot a mess—"but a vivid, splashy, even courageous mess".[56] Slant Magazine described it as a "pompous, overwrought," but nonetheless "glorious concept album".[65] Uncut was more critical and wrote in a mixed review that although the album was heavily politically focused, "slam-dancing is still possible".[66] In a negative review, Robert Christgau of The Village Voice called the album a "dud" and asserted that Armstrong's lyrics eschew "sociopolitical content" for "the emotional travails of two clueless punks—one passive, one aggressive, both projections of the auteur", adding that "there's no economics, no race, hardly any compassion."[63]

Ian Winwood of Kerrang! called it a "modern day masterpiece".[67] Josh Tyrangiel of Time said, "For an album that bemoans the state of the union, it is irresistibly buoyant."[8]

Accolades[edit]

In 2005, American Idiot won a Grammy Award for Best Rock Album and was nominated in six other categories including Album of the Year.[68][69] The album helped Green Day win seven of the eight awards it was nominated for at the 2005 MTV Video Music Awards; the "Boulevard of Broken Dreams" video won six of those awards. A year later, "Boulevard of Broken Dreams" won a Grammy Award for Record of the Year.[70] In 2009, Kerrang! named American Idiot the best album of the decade,[71] NME ranked it number 60 in a similar list,[72] and Rolling Stone ranked it 22nd.[73] Rolling Stone also listed "Boulevard of Broken Dreams" and "American Idiot" among the 100 best songs of the 2000s, at number 65 and 47 respectively.[74][75] In 2005, the album was ranked number 420 in Rock Hard magazine's book of The 500 Greatest Rock & Metal Albums of All Time.[76] In 2012, the album was ranked number 225 on Rolling Stone's list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[77]

| Publication | Accolade | Rank | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NARM | The Definitive 200 Albums of All Time[78] | 61 | ||

| Rolling Stone | The 100 Greatest Albums of the Decade[73][79] | 22 | ||

| Rolling Stone | 500 Greatest Albums of All Time[77] | 225 | ||

| Kerrang | 100 Greatest Rock Albums of All Time[80] | 13 | ||

| Kerrang | The 50 Best Rock Albums of the 2000s[81] | 1 | ||

| NME | The Top 100 Greatest Albums of the Decade[82] | 60 | ||

| NPR | The Decade's 50 Most Important Recordings[83] | * | ||

| Robert Dimery | 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die[84] | * | ||

| Rhapsody | The 100 Best Pop Albums of the Decade[85] | 6 | ||

| Entertainment Weekly | New Classics: The 100 Best Albums from 1983 to 2008.[86] | 6 | ||

| IGN | The 25 Best Rock Albums of the Last Decade[87] | * | ||

| Loudwire | The 100 Best Hard Rock + Metal Albums of the 21st Century[88] | 10 | ||

| Spinner | Best Albums of the 2000s[89] | 14 | ||

| PopMatters | The 100 Best Albums of the 2000s[90] | 36 | ||

| (*) denotes an unranked list | ||||

International awards and nominations[edit]

| Ceremony | Award | Year | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| American Music Awards | Favorite Pop/Rock Album | 2005 | Won[91] |

| Billboard Music Awards | Album of the Year | 2005 | Nominated[92] |

| Japan Gold Disc Awards | Best 10 International Rock & Pop Albums of the Year | 2005 | Won[93] |

| Juno Awards | Best International Album of the Year | 2005 | Won[93] |

| MTV Europe Music Awards | Best Album | 2005 | Won[93] |

| NME Awards | Best Album | 2005 | Nominated[94][95] |

| Teen Choice Awards | Music Album | 2005 | Nominated[96][97] |

| BRIT Awards | Best International Album | 2006 | Won[98] |

Grammy Awards and nominations[edit]

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | American Idiot | Album of the Year | Nominated[99] |

| Best Rock Album | Won[100] | ||

| "American Idiot" | Record of the Year | Nominated[101] | |

| Best Rock Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal | Nominated[101] | ||

| Best Rock Song | Nominated[101] | ||

| Best Music Video | Nominated[101] | ||

| 2006 | "Boulevard of Broken Dreams" | Record of the Year | Won[102] |

Release and commercial performance[edit]

American Idiot was released on September 21, 2004.[103][65] It became Green Day's first number one album in the United States, selling 267,000 copies in its first week of release, their biggest opening sales week.[104] The album became 2005's fourth-highest seller, moving over 3.4 million units.[105] American Idiot remained in the top 10 of the Billboard 200 upwards of a year following its release,[106] staying on the chart for 101 weeks.[2] The album also debuted at number one in the United Kingdom, selling 89,385 copies in the first week.[107] The album has received certification awards in many territories; among them being certified six times platinum status in the United States and Australia,[108][109] and diamond in Canada.[110]

The album spawned five singles: "American Idiot", "Boulevard of Broken Dreams", "Holiday", "Wake Me Up When September Ends", and "Jesus of Suburbia". The title track was released to active rock and alternative radio stations preceding the album on August 6, 2004.[111] Two weeks later, it became the band's first song to place on the Billboard Hot 100, where it peaked at number 61.[112] Internationally, it peaked much higher, reaching number three in the United Kingdom, and debuting at number one in Canada.[citation needed] The song was released at a time before Billboard began accounting for internet sales in its chart positions;[113] after "Boulevard of Broken Dreams" was released as the second single on November 29,[114] it would peak at number two on the Hot 100.[112] "Holiday" and "Wake Me Up When September Ends" would follow as the third and fourth singles on March 14 and June 13, 2005, respectively,[115][116] the former peaking at number nineteen and latter peaking at number six on the Hot 100.[112] "Jesus of Suburbia" was released on November 14, 2005, as the final single; the band played the entire nine-minute composition for the longest performance to that point on Top of the Pops in the week preceding the single.[117] It did not perform as well on the charts as the preceding four songs.[118]

Samuel Bayer directed music videos for all five of the album's singles. In 2005, commenting on the success American Idiot brought the band, he stated, "The Billie Joe that I work with now is not the same guy that walked onto the "American Idiot" set a year ago. Now, he's a rock star. They were famous. They had done big stuff. But it's transcended that. But he hasn't changed. And they haven't changed. They're three friends who love one another."[119] Courtney Love also commented on the success of the band, stating "Billie Joe looks absolutely beautiful. You know how when people get super A-list, their face gets prettier? I think it's perception. It's something that happens in your subconscious".[119] At the time of American Idiot's release, the album was not sold in Wal-Mart due to its explicit content.[19]

As of 2014, American Idiot has sold 6.2 million albums in the United States, making it second to Dookie within their catalogue.[105] In January 2013, its worldwide sales were estimated at 16 million copies.[2]

Touring[edit]

The band underwent "a significant image change" surrounding the album's promotion, and they began wearing black and red uniforms onstage. Armstrong considered it a natural extension of his showmanship, which began in his childhood.[11] Touring in support of the album began in the US, where the band performed in conservative stronghold states like Texas, Tennessee, and Georgia. The group headlined arenas that were only "60 to 75 percent full" and were often booed for performing songs from the album. Armstrong often chanted "Fuck George W. Bush!"[120] Jonah Weiner of Blender likened the band's live performances of the time to an "anti-Bush rally."[11] Armstrong admitted that they did "everything to piss people off," including wearing a Bush mask onstage in weeks preceding the election.[7]

The European tour sold 175,000 tickets in less than an hour.[7] In April, the band began a one-month US arena tour.[7] The band soon began playing stadiums, performing at New Jersey's Giants Stadium, San Francisco's SBC Park, and Los Angeles' Home Depot Center between September and October 2005.[106]

Legacy[edit]

John Colapinto of Rolling Stone summarized its immediate impact in a 2005 story:[121]

American Idiot [...] gives voice to the disenfranchised suburban underclass of Americans who feel wholly unrepresented by the current leadership of oilmen and Ivy Leaguers, and who are too smart to accept the "reality" presented by news media who sell the government's line of fear and warmongering.

Jon Pareles of The New York Times deemed it "both a harbinger and a beneficiary of the Bush administration's plummeting approval, selling steadily through 2005 as the response to Hurricane Katrina and the protracted war in Iraq turned much of the country against the government."[122] "Wake Me Up When September Ends" became symbolic during various events such as the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina; one online blogger paired the song with television coverage of the disaster, creating a viral video.[123]

Ian Winwood of Kerrang! said that the album pushed rock music back into the mainstream.[67] American Idiot was a career comeback for Green Day,[7] and their unexpected maturation "stunned the music industry."[8] In 2020 Rolling Stone placed the album at 248 on their updated list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[124]

Adaptations[edit]

In late 2005, DJ Party Ben and producer Team9, under the shared alias Dean Gray (a spoonerism of "Green Day"), released an online-only mash-up version of the album—called American Edit. This became a cause célèbre when a cease and desist order was served by Green Day's record label.[125] Tracks include "American Edit", "Dr. Who on Holiday", "Novocaine Rhapsody", and "Boulevard of Broken Songs." Billie Joe Armstrong later stated that he heard one of the songs on the radio and "enjoyed it."[125]

Stage musical[edit]

An American Idiot stage musical adaptation premiered at the Berkeley Repertory Theatre in September 2009. The musical was a collaboration between Green Day and director Michael Mayer.[126] Green Day did not appear in the production, but the show featured an onstage band.[127] The production transferred to Broadway at the St. James Theatre, and opened in April 2010. The show received mixed reviews from critics, but received a rave review from The New York Times.[128] The show features all of the songs from the album American Idiot, including B-sides, as well as songs from Green Day's follow-up album, 21st Century Breakdown.[129] Armstrong appeared in the Broadway production as St. Jimmy multiple times.[130][131] With his return in 2011, the show grossed over $1 million.[132]

American Idiot won two Tony Awards: Best Scenic Design of a Musical for Christine Jones and Best Lighting Design of a Musical for Kevin Adams. It also received a nomination for Best Musical.[133] The Broadway production closed in April 2011, after 27 previews and 421 regular performances. The first national tour started in late 2011.[134] A documentary regarding the musical, titled Broadway Idiot, was released in 2013.[135]

Film[edit]

Billie Joe Armstrong had at one point, prior to its release, suggested the album would make good material for an adapted feature film.[31] Shortly after the album was released, there was speculation that American Idiot might be made into a film. In an interview with VH1, Armstrong said, "We've definitely been talking about someone writing a script for it, and there's been a few different names that have been thrown at us. It sounds really exciting, but for right now it's just talk."[136] On June 1, 2006, Armstrong announced in an interview with MTV that the movie was "definitely unfolding" and that "every single week there's more ideas about doing a film for American Idiot, and it's definitely going to happen".[137]

In April 2011, production company Playtone optioned the musical to develop a film version, and Universal Pictures began initial negotiations to distribute it. Michael Mayer, who directed the Broadway production, was named as director. Dustin Lance Black was initially hired to adapt the musical.[138] Billie Joe Armstrong was asked to star as St. Jimmy, and the film was proposed for a 2013 release.[139] Armstrong later posted on his Twitter account that he had not "totally committed" to the role but was interested in it.[140]

In March 2014, playwright Rolin Jones told the Hartford Courant that he was writing a new screenplay for the film. Comparing it to the musical, Jones said, "The idea is to get it a little dirtier and a little nastier and translate it into visual terms. There's not going to be a lot of dialogue and it probably should be a little shorter, too. After that, it just takes its 'movie time' in getting done". He expected to finish the script by the end of the month.[141]

In October 2016, in an interview with NME, Armstrong revealed that the film was now being made at HBO and the script was getting rewrites. He confirmed he would reprise his Broadway role as St. Jimmy.[142] In November 2016, Armstrong stated that the film was "going to be a lot different from the musical. It's kind of, more surreal but I think there's going to be parts of it that might offend people – which is good. I think it's a good time to offend people. I think there's just going to be a lot of imagery that we couldn't pull off in the musical in the stage version. You know, I don't want to give away too much, but it will be shocking in a way which makes you think."[143]

In February 2020, Billie Joe Armstrong revealed to NME that plans for the film adaptation of American Idiot have been "pretty much scrapped", without providing any more details as to the reason.[144]

Documentary[edit]

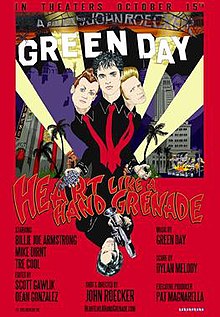

| Heart Like a Hand Grenade | |

|---|---|

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | John Roecker |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | John Roecker |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by |

|

Production company | Crazy Cow Productions |

| Distributed by | Abramorama |

Release date | October 15, 2015 |

Running time | 97 minutes |

| Language | English |

Heart Like a Hand Grenade is a 2015 film featuring Green Day during the recording of American Idiot. It was directed by John Roecker and filmed over the process of fifteen months between 2003 and 2004.[145] It is a documentary about the songwriting and recording process of the album.[146]

Release history[edit]

The film had a limited, one night release in Hollywood at Grauman's Egyptian Theatre on March 25, 2009, to a crowd of more than 400 people.[147]

On July 15, 2014, director John Roecker announced on his Facebook page that the film would be released to the public. On May 18, 2015, Roecker mentioned on his personal Facebook page that the sound mix was done and that the movie was in Warner Brothers' hands: "I am happy to announce that Heart Like A Hand Grenade: The Making of American Idiot is finished. Sound mix done and now off to Warner Brothers. I want to thank Scott Gawlik and Dylan Melody for their amazing talent and making this film incredible. Also thank you Chris Dugan for creating an American Idiot overture the one I wanted 11 years ago!"[148]

On June 12, 2015, director John Roecker confirmed on his Facebook page that Warner Brothers had a release date/period for the film: "Deal with Warners is Done! Praise Satan! See you in September. Heart Like A Hand Grenade: The Making of American Idiot teaser coming soon. I want to thank my brothers Dylan Melody, Dean Gonzalez, Scott Gawlik for making my film how I envisioned it. Eleven years but it has been worth it...you will not be disappointed this film is the shit."[149]

Heart Like a Hand Grenade made its world premiere on October 8, 2015, at the 38th Mill Valley Film Festival, and it was released to theaters in the US the following week. It received a worldwide release on November 11, and it was available on DVD and digital release on November 13.[150]

Track listing[edit]

All lyrics written by Billie Joe Armstrong, except where noted; all music composed by Green Day.[151]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "American Idiot" | 2:54 |

| 2. | "Jesus of Suburbia"

| 9:08

|

| 3. | "Holiday" | 3:52 |

| 4. | "Boulevard of Broken Dreams" | 4:22 |

| 5. | "Are We the Waiting" | 2:42 |

| 6. | "St. Jimmy" | 2:56 |

| 7. | "Give Me Novacaine" ([a]) | 3:25 |

| 8. | "She's a Rebel" | 2:00 |

| 9. | "Extraordinary Girl" | 3:33 |

| 10. | "Letterbomb" | 4:05 |

| 11. | "Wake Me Up When September Ends" | 4:45 |

| 12. | "Homecoming"

| 9:18

|

| 13. | "Whatsername" | 4:14 |

| Total length: | 57:12 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 14. | "Favorite Son" | 2:06 |

| Total length: | 59:18 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "American Idiot" | 4:17 |

| 2. | "Jesus of Suburbia" I. "Jesus of Suburbia" II. "City of the Damned" III. "I Don't Care" IV. "Dearly Beloved" V. "Tales of Another Broken Home" | 9:22 |

| 3. | "Holiday" | 4:33 |

| 4. | "Are We the Waiting" | 3:18 |

| 5. | "St. Jimmy" | 2:57 |

| 6. | "Boulevard of Broken Dreams" | 4:41 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Making of 'Boulevard of Broken Dreams' & 'Holiday'" | |

| 2. | "Boulevard of Broken Dreams" (music video) | |

| 3. | "Holiday" (music video) |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "American Idiot" | 2:54 |

| 2. | "Jesus of Suburbia"

| 9:08

|

| 3. | "Holiday / Boulevard of Broken Dreams" | 8:13 |

| 4. | "Are We the Waiting / St. Jimmy" | 5:38 |

| 5. | "Give Me Novacaine / She's a Rebel" | 5:26 |

| 6. | "Extraordinary Girl / Letterbomb" | 7:39 |

| 7. | "Wake Me Up When September Ends" | 4:45 |

| 8. | "Homecoming"

| 9:18

|

| 9. | "Whatsername" | 4:14 |

| 10. | "Too Much Too Soon" (deluxe bonus track[156][157]) | 3:30 |

| 11. | "Shoplifter" (deluxe bonus track[156][157]) | 1:50 |

| 12. | "Governator" (deluxe bonus track[156][157]) | 2:31 |

| 13. | "Jesus of Suburbia" (music video) (iTunes deluxe edition bonus track[158]) | 9:05 |

- In 2015, Kerrang! Magazine released a cover album of American Idiot, covered by various artists.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "American Idiot" (5 Seconds of Summer) | 3:02 |

| 2. | "Jesus of Suburbia" (Rise to Remain) | 9:12 |

| 3. | "Holiday" (The Blackout) | 3:24 |

| 4. | "Boulevard of Broken Dreams" (Neck Deep) | 3:54 |

| 5. | "Are We the Waiting" (You Me at Six) | 2:41 |

| 6. | "St. Jimmy" (Bowling for Soup) | 3:03 |

| 7. | "Give Me Novacaine" (Escape the Fate) | 3:32 |

| 8. | "She's a Rebel" (Falling in Reverse) | 2:20 |

| 9. | "Extraordinary Girl" (Frank Iero) | 4:35 |

| 10. | "Letterbomb" (LostAlone) | 3:55 |

| 11. | "Wake Me Up When September Ends" (The Defiled) | 4:25 |

| 12. | "Homecoming" (Lonely the Brave) | 8:58 |

| 13. | "Whatsername" (New Politics) | 3:14 |

| 14. | "Welcome To Paradise" (State Champs, bonus track) | 3:37 |

| 15. | "Basket Case" (The Swellers, bonus track) | 2:58 |

| Total length: | 62:50 | |

Personnel[edit]

Credits adapted from the liner notes of American Idiot.[151]

Green Day

- Billie Joe Armstrong – lead and backing vocals, guitars

- Mike Dirnt – bass guitar, backing vocals; lead vocals on "Nobody Likes You" (section in "Homecoming") and "Governator" (deluxe bonus track)

- Tré Cool – drums, percussion; lead vocals on "Rock and Roll Girlfriend" (section in "Homecoming")

Additional musicians

- Rob Cavallo – piano

- Jason Freese – saxophone

- Kathleen Hanna – guest vocals on "Letterbomb"

Production

- Rob Cavallo – producer

- Green Day – producers

- Doug McKean – engineer

- Brian "Dr. Vibb" Vibberts – assistant engineer

- Greg "Stimie" Burns – assistant engineer

- Jimmy Hoyson – assistant engineer

- Joe Brown – assistant engineer

- Dmitar "Dim-e" Krnjaic – assistant engineer

- Chris Dugan – additional engineering

- Reto Peter – additional engineering

- Chris Lord-Alge – mixing

- Ted Jensen – mastering

Artwork

- Chris Bilheimer – cover art

Charts[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

Decade-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications and sales[edit]

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina (CAPIF)[247] | 2× Platinum | 80,000^ |

| Australia (ARIA)[248] | 6× Platinum | 420,000^ |

| Austria (IFPI Austria)[249] | 2× Platinum | 60,000* |

| Belgium (BEA)[250] | Platinum | 50,000* |

| Brazil (Pro-Música Brasil)[252] | Gold | 93,627[251] |

| Canada (Music Canada)[253] | Diamond | 1,000,000‡ |

| Denmark (IFPI Danmark)[254] | 2× Platinum | 80,000^ |

| Finland (Musiikkituottajat)[255] | Gold | 23,133[255] |

| France (SNEP)[256] | Platinum | 300,000* |

| Germany (BVMI)[257] | 4× Platinum | 800,000‡ |

| Greece (IFPI Greece)[171] | Platinum | 20,000^ |

| Hungary (MAHASZ)[258] | Gold | 10,000^ |

| Ireland (IRMA)[259] | 8× Platinum | 120,000^ |

| Israel | — | 20,000[260] |

| Italy sales 2004–2005 |

— | 250,000[261] |

| Italy (FIMI)[262] sales since 2009 |

2× Platinum | 100,000‡ |

| Japan (RIAJ)[263] | 2× Platinum | 500,000^ |

| Mexico (AMPROFON)[264] | Platinum | 100,000^ |

| Netherlands (NVPI)[265] | Gold | 40,000^ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[266] | 4× Platinum | 60,000^ |

| Portugal (AFP)[267] | Gold | 20,000^ |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[268] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| Sweden (GLF)[269] | Platinum | 60,000^ |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[270] | 2× Platinum | 80,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[271] | 8× Platinum | 2,400,000‡ |

| United States (RIAA)[272] | 6× Platinum | 6,200,000[105] |

| Summaries | ||

| Europe (IFPI)[273] | 4× Platinum | 4,000,000* |

| Worldwide | — | 16,000,000[2] |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- the majority of songs had been combined on their audio files, meaning that on Cd's, it's impossible to listen to certain songs without listening to the other ones first.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Green Day: Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on April 23, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Robinson, Joe (January 4, 2013). "Green Day, 'American Idiot' – Career-saving albums". Diffuser. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017.

- ^ "Warning Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 23, 2010. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ Spitz 2006, p. 143.

- ^ a b c d e Sinclair, Tom (February 11, 2005). "Sitting on Top of the World". Entertainment Weekly. pp. 25–31. ISSN 1049-0434.

- ^ a b c d Baltin, Steve (January 1, 2005). "Green Day". AMP. pp. 62–66. OCLC 64709668.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hendrickson, Matt (February 24, 2005). "Green Day and the Palace of Wisdom". Rolling Stone. No. 968. New York City. ISSN 0035-791X. Archived from the original on June 8, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ a b c Tyrangiel, Josh (January 31, 2005). "Green Party". Time. Vol. 165, no. 5. pp. 60–62. ISSN 0040-781X.

- ^ a b Bryant, Tom (December 3, 2005). "Blaze of Glory". Kerrang!. No. 1085. London. ISSN 0262-6624.

- ^ a b Lanham 2004, p. 118.

- ^ a b c d Weiner 2006, p. 98.

- ^ Spitz 2006, p. 152.

- ^ Pappademas 2004, p. 66.

- ^ Trendell, Andrew (November 18, 2016). "Green Day reveal the fate of 'lost' pre-'American Idiot' album 'Cigarettes And Valentines'". NME. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- ^ Spitz 2006, p. 153.

- ^ a b c Pappademas 2004, p. 67.

- ^ Spitz 2006, p. 154.

- ^ a b c Lanham 2004, p. 120.

- ^ a b c d e f Sharples, Jim (October 1, 2004). "Rebel Waltz". Big Cheese. No. 56. pp. 42–46. ISSN 1365-358X.

- ^ Spitz 2006, p. 150.

- ^ Spitz 2006, p. 151.

- ^ a b c Winwood 2010, p. 50.

- ^ Spitz 2006, p. 166.

- ^ a b c d e f g DiPerna 2005, p. 28.

- ^ a b Zulaica 2004, p. 65.

- ^ a b c Zulaica 2004, p. 67.

- ^ a b Zulaica 2004, p. 62.

- ^ a b c Zulaica 2004, p. 66.

- ^ Lanham 2004, p. 119.

- ^ Pappademas 2004, p. 68.

- ^ a b c d Lanham 2004, p. 122.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lanham 2004, p. 116.

- ^ Winwood, Ian (May 9, 2012). "The Secrets Behind The Songs: "American Idiot"". Kerrang!. No. 1414. London. ISSN 0262-6624.

- ^ a b c d e f g DiPerna 2005, p. 26.

- ^ Pappademas 2004, p. 65.

- ^ Zulaica 2004, p. 64.

- ^ a b DiPerna 2005, p. 24.

- ^ a b Bradman, E.E.; Buddingh, Terry (January 18, 2006). "Ready Set Go!: Studio Secrets of Mike Dirnt and Green Day Producer Rob Cavallo". Bass Guitar. ISSN 1476-5217.

- ^ Tupper, Dave (December 1, 2004). "Birth of Tre Cool". Drummer Magazine. pp. 46–52. ISSN 1741-2153.

- ^ a b DeRogatis, Jim (September 19, 2004). "Green Day, 'American Idiot' (Warner Music Group)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ Rizzo, Frank. "Musical 'American Idiot' Explodes With Intense Theatricality". The Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on July 10, 2013. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ^ "Briefs Roundup". Los Angeles Daily News. Archived from the original on August 2, 2008. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- ^ Harvell, Jess (May 22, 2009). "Green Day: 21st Century Breakdown Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on May 23, 2009. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- ^ Stegall, Tim (March 22, 2022). "15 best punk albums of 2004, from Green Day to My Chemical Romance". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ Carter, Emily (July 22, 2020). "Green Day: Every album ranked from worst to best". Kerrang!. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ Staff (March 15, 2018). "The 50 Best Punk Albums Of All Time". Louder. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

Green Day broke big with their storytelling magnum opus American Idiot in 2004, but punk rock concept albums weren't a new species.

- ^ O'Neil, Tim (October 14, 2004). "Green Day: American Idiot". PopMatters. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ Spitz 2006, p. 165.

- ^ a b c DiPerna 2005, p. 27.

- ^ Durham, Victoria (March 1, 2005). "Green Day: Let The Good Times Roll". Rock Sound. No. 70. New York City. pp. 50–55. ISSN 1465-0185.

- ^ Lanham 2004, p. 117.

- ^ Spitz 2006, p. 169.

- ^ a b "Reviews for American Idiot by Green Day". Metacritic. Archived from the original on September 11, 2012. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "American Idiot – Green Day". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 15, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ a b Browne, David (September 24, 2004). "American Idiot". Entertainment Weekly. New York. Archived from the original on November 10, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ a b Lynskey, Dorian (September 17, 2004). "Green Day, American Idiot". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on January 18, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ "Green Day: American Idiot". Mojo. No. 131. London. October 2004. p. 106.

- ^ a b "Green Day: American Idiot". NME. London. September 18, 2004. p. 65.

- ^ a b Loftus, Johnny (September 24, 2004). "Green Day: American Idiot". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 18, 2009. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ a b "Green Day: American Idiot". Q. No. 220. London. November 2004. p. 110.

- ^ a b Sheffield, Rob (September 30, 2004). "American Idiot". Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on March 3, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ a b Gundersen, Edna (September 21, 2004). "Green Day, American Idiot". USA Today. McLean. Archived from the original on November 13, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (January 25, 2005). "Harmonies and Abysses". The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on December 6, 2014. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (September 26, 2004). "Putting Her Money Where Her Music Video Is". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Cinquemani, Sal (September 20, 2004). "Green Day: American Idiot". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on October 31, 2013. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ "Green Day – American Idiot". Uncut. No. 90. November 2004. p. 119. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ a b Winwood 2010, p. 49.

- ^ "2004 Grammy Award Winners". Grammy Awards. Archived from the original on February 11, 2015. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ^ "Green Day's American Idiot Nominated for Seven Grammy Awards". GoWEHO. December 13, 2004. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ^ "2005 Grammy Award Winners". Grammy Awards. Archived from the original on November 10, 2014. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ^ "Kerrang! Top 50 albums of the 21st Century". Kerrang!. August 5, 2009.

- ^ "The Top 100 Greatest Albums of the Decade". NME. Archived from the original on November 20, 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ a b "100 Best Albums of the Decade: #22-#21". Rolling Stone. December 9, 2009. Archived from the original on December 13, 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ "100 Best Songs of the Decade: #68–65". Rolling Stone. December 9, 2009. Archived from the original on December 13, 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ "100 Best Songs of the Decade: #48–45". Rolling Stone. December 9, 2009. Archived from the original on December 13, 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ Best of Rock & Metal – Die 500 stärksten Scheiben aller Zeiten (in German). Rock Hard. 2005. p. 42. ISBN 3-89880-517-4.

- ^ a b "500 Greatest Albums of All Time: Green Day, 'American Idiot'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ "The Definitive 200: Top Albums of All Time". WCBS-TV. March 7, 2007. Archived from the original on June 7, 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- ^ "Rolling Stone's 100 Best Albums, Songs of The '00s". Stereogum. December 10, 2009. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

- ^ "A Definitive Ranking of Every Green Day Album". Consequence. February 17, 2023. Archived from the original on January 9, 2024. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ "The 50 Best Rock Albums of the 2000s". Kerrang!. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ^ "The Top 100 Greatest Albums of the Decade". NME. Archived from the original on November 20, 2009. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- ^ Boilen, Bob (November 16, 2009). "The Decade's 50 Most Important Recordings". NPR. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- ^ Dimery, Robert; Lydon, Michael (2014). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. Universe. ISBN 978-0-7893-2074-2.

- ^ Bardeen, Sarah. "100 Best Pop Albums of the Decade". Rhapsody. Archived from the original on November 2, 2010.

- ^ "The New Classics: Music". Entertainment Weekly. June 18, 2007. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ Grischow, Chad (December 16, 2011). "25 Best Rock Albums of the Last Decade". IGN. Archived from the original on January 4, 2012.

- ^ "The 100 Best Hard Rock + Metal Albums of the 21st Century". Loudwire. Archived from the original on November 30, 2018. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ "Best Albums of the 2000s". Spinner. Archived from the original on December 15, 2009. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ Ramirez, AJ (November 2, 2020). "The 100 Best Albums of the 2000s: 40–21". PopMatters. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ "2005 American Music Awards Winners". Billboard. November 23, 2005. Archived from the original on October 1, 2014. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ "2005 Billboard Music Awards Finalists". Billboard. November 29, 2005. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c Fojas, Sara (June 20, 2016). "Anthem of the Youth". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ^ "2005 NME Award nominations". Manchester Evening News. June 30, 2005. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ "2005". NME. February 28, 2005. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ "FOX Announces Nominees for "The 2005 Teen Choice Awards"". The Futon Critic. June 6, 2005. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ "Grownups dominate Teen Choice Awards". The Gazette. August 16, 2005. Archived from the original on August 15, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ "Brit Awards 2006: The winners". BBC News. February 15, 2006. Archived from the original on January 14, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ Lipshutz, Jason. "Top 10 Biggest GRAMMY Upsets of the Past 10 Years". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ^ Vaziri, Aidin (February 14, 2005). "2005 GRAMMY Awards / Ray Charles' posthumous haul is heftiest: 8 awards. Alicia Keys wins big; Green Day gets best rock album". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 30, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Grammy Award nominees in top categories". USA Today. December 7, 2004. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ^ "Winners – Record of the Year". Grammy Awards. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ^ Manning, Craig (September 21, 2004). "Green Day – American Idiot". Chorus.fm. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ "The 'American' Way: Green Day Debuts At No. 1". Billboard. September 29, 2004. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013.

- ^ a b c Payne, Chris (September 20, 2014). "Green Day's 'American Idiot' Turns 10: Classic Track-by-Track Album Review". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015.

- ^ a b "Green Day Go Big". Rolling Stone. No. 973. New York City. May 5, 2005. ISSN 0035-791X.

- ^ Jones, Alan (October 14, 2016). "Official Charts Analysis: Green Day claim top spot with Revolution Radio". Music Week. Archived from the original on July 30, 2023. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ "ARIA Charts". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on June 27, 2010. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- ^ "RIAA Certifications". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum Certification – July 2005". Canadian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on October 19, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ "Going for Adds" (PDF). Radio & Records. No. 1567. August 6, 2004. p. 23. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Green Day". Billboard. August 21, 2004. Archived from the original on March 29, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Mayfield, Geoff (August 4, 2007). "Billboard Hot 100 To Include Digital Streams". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved July 30, 2007.

- ^ "Going for Adds" (PDF). Radio & Records. No. 1583. November 26, 2004. p. 21. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ "New Releases: Singles". Music Week. March 12, 2005. p. 29.

- ^ "Going for Adds" (PDF). Radio & Records. No. 1610. June 10, 2005. p. 19. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ "Green Day play 'longest ever' Top Of The Pops song". NME. October 31, 2005. Archived from the original on June 16, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Childers, Chad (June 28, 2012). "No. 10: Green Day, 'Jesus of Suburbia' – Top 21st century hard rock songs". Loudwire. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

And while singles such as 'American Idiot,' 'Boulevard of Broken Dreams,' 'Holiday,' and 'Wake Me Up When September Ends' would achieve bigger chart success, it was the five-part suite, 'Jesus of Suburbia,' which caught the attention of many with its epic storytelling.

- ^ a b Spitz 2006, p. 179.

- ^ Winwood 2010, p. 52.

- ^ Colapinto, John (November 17, 2005). "Green Day: Working Class Heroes". Rolling Stone. No. 987. New York City. pp. 50–56. ISSN 0035-791X. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (April 29, 2009). "The Morning After 'American Idiot'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 12, 2013. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- ^ Boxer, Sarah (September 24, 2005). "Art of the Internet: A Protest Song, Reloaded". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. September 22, 2020. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Montgomery, James (December 20, 2005). "Green Day Mash-Up Leads to Cease and Desist Order". MTV. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (March 29, 2009). "Punk CD Is Going Theatrical". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- ^ Hurwitt, Robert (March 31, 2009). "Green Day's hits turn into Berkeley Rep musical". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 18, 2011.

- ^ Isherwood, Charles (April 21, 2010). "Stomping Onto Broadway With a Punk Temper Tantrum". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 29, 2012.

- ^ "American Idiot 09/10". Berkeley Repertory Theatre. Archived from the original on July 23, 2010. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- ^ "Billie Joe Armstrong Joins 'American Idiot' On Broadway". Huffington Post. September 27, 2010. Archived from the original on September 30, 2010. Retrieved September 27, 2010.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth (November 30, 2010). "Billie Joe Armstrong Will Be St. Jimmy in American Idiot in Early 2011". Playbill. Archived from the original on December 3, 2010. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ^ "Broadway Grosses: American Idiot Joins Million-Dollar Club". Broadway.com. February 22, 2011. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017.

- ^ "Who's Nominated?". Tony Awards. Archived from the original on May 7, 2010. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth (April 5, 2011). "Billie Joe Armstrong Jumps into American Idiot April 5, Playing Final Weeks". Playbill. Archived from the original on April 6, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ "WORLD PREMIERE!". Broadway Idiot official site. January 31, 2013. Archived from the original on June 22, 2013.

- ^ Moss, Corey (September 21, 2004). "Green Day Considering Movie Version of American Idiot". VH1. Archived from the original on May 11, 2005. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- ^ Moss, Corey (June 1, 2006). "Green Day Promise Next LP Will Be "An Event" – News Story". MTV. Archived from the original on January 8, 2024. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ Kit, Borys (April 12, 2011). ""American Idiot" movie lands at Universal". Reuters. Archived from the original on April 16, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ^ Chu, Karen (November 6, 2011). "Tom Hanks' Playtone Productions Announces Neil Gaiman's 'American Gods,' Mattel's 'Major Matt Mason,' Green Day's 'American Idiot' (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 9, 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ^ Armstrong, Billie Joe. "Haven't totally committed to St Jimmy for AI movie. Yes, I'm interested. Yes someone jumped the gun." Twitter. Archived from the original on April 16, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ "Yale Rep's 'These Paper Bullets' Features New Songs From Green Day's Billie Joe Armstrong". Hartford Courant. March 12, 2014. Archived from the original on March 20, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ Trendell, Andrew (July 10, 2016). "Green Day's 'American Idiot' movie has 'green light from HBO'". NME. Archived from the original on October 7, 2016. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- ^ Trendell, Andrew (November 17, 2016). "Green Day give update on 'surreal, offensive' 'American Idiot' movie". NME. Archived from the original on February 4, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ Reilly, Nick (February 10, 2020). "Green Day's 'American Idiot' movie has been "pretty much scrapped"". NME. Archived from the original on February 4, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ Talcott, Christina (January 27, 2006). "John Roecker's 'Freaky' Puppet Show". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 12, 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Green Day Heart Like A Hand Grenade". Green Day. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- ^ Wilson, Pamela (March 26, 2009). "'Heart Like a Hand Grenade' fuses punk rock antics with superstar vision". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Facebook". Facebook. Archived from the original on September 16, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ "Facebook". Facebook. Archived from the original on September 16, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ Childers, Chad (October 8, 2015). "Green Day Reveal 'Heart Like a Hand Grenade' Theatrical Screenings + Release Date". Loudwire. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ^ a b Green Day (2004). American Idiot (booklet). Reprise Records. 9362-48777-2.

- ^ a b Green Day (2004). American Idiot (booklet). Reprise Records. WPCR-12106-7.

- ^ Green Day (2005). American Idiot (booklet). Reprise Records. 9362-49391-2.

- ^ "iTunes – Music – American Idiot". iTunes Store. Archived from the original on November 13, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ "Amazon.com: American Idiot (Regular Edition) [Explicit]: Green Day: MP3 Downloads". Amazon. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ a b c "iTunes – Music – American Idiot (Holiday Edition Deluxe)". iTunes Store. Archived from the original on November 18, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Amazon.com: American Idiot (Deluxe) [Explicit]: Green Day: MP3 Downloads". Amazon. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ "iTunes – Music – American Idiot (Deluxe Version)". iTunes Store. September 21, 2004. Archived from the original on August 18, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ "Ranking Semanal desde 27/02/2005 hasta 05/03/2005" (in Spanish). Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on March 10, 2005. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Australiancharts.com – Green Day – American Idiot". Hung Medien. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Green Day – American Idiot" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Green Day – American Idiot" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Green Day – American Idiot" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Green Day Chart History (Canadian Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Danishcharts.dk – Green Day – American Idiot". Hung Medien. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Green Day – American Idiot" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Eurocharts: Album Sales". Billboard. Vol. 117, no. 6. February 5, 2005. p. 42. ISSN 0006-2510. Archived from the original on September 16, 2017.

- ^ "Green Day: American Idiot" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – Green Day – American Idiot". Hung Medien. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Green Day – American Idiot" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ a b "Ελληνικό Chart – Top 50 Ξένων Aλμπουμ" (in Greek). IFPI Greece. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Album Top 40 slágerlista – 2005. 10. hét" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Irish-charts.com – Discography Green Day". Hung Medien. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ "Italiancharts.com – Green Day – American Idiot". Hung Medien. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "アメリカン・イディオット | グリーン・デイ" [American Idiot | Green Day] (in Japanese). Oricon. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ a b "Top 100 Album" (PDF). Asociación Mexicana de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2010. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ^ "Charts.nz – Green Day – American Idiot". Hung Medien. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Green Day – American Idiot". Hung Medien. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Oficjalna lista sprzedaży :: OLiS - Official Retail Sales Chart". OLiS. Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Portuguesecharts.com – Green Day – American Idiot". Hung Medien. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ 26, 2004/40/ "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Top 100 Albumes – Lista de los titulos mas vendidos del 20.09.04 al 26.09.04" (PDF) (in Spanish). Productores de Música de España. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – Green Day – American Idiot". Hung Medien. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Green Day – American Idiot". Hung Medien. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Official Rock & Metal Albums Chart Top 40". Official Charts Company. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ "Green Day Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Green Day Chart History (Top Rock Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Green Day Chart History (Top Tastemaker Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "Top Stranih [Top Foreign]" (in Croatian). Top Foreign Albums. Hrvatska diskografska udruga. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Czech Albums – Top 100". ČNS IFPI. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Green Day Chart History (Top Catalog Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Green Day Chart History (Top Alternative Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – End of Year Charts – Top 100 Albums 2004". ARIA Charts. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ^ "Jahreshitparade Alben 2004" (in German). austriancharts.at. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "Chart of the Year 2004". TOP20.dk. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts 2004" (in German). Media Control Charts. Archived from the original on April 12, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Classifica annuale 2004 (dal 29.12.2003 al 02.01.2005) – Album & Compilation" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ "年間 アルバムランキング 2004年度" [Oricon Year-end Albums Chart of 2004] (in Japanese). Oricon. Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ^ "Top Selling Albums of 2004". Recorded Music NZ. Archived from the original on September 7, 2013. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ^ "Årslista Album – År 2004" (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Swedish Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on January 6, 2015. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Årslista Album (inkl samlingar), 2004" (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ "Schweizer Jahreshitparade 2004" (in German). hitparade.ch. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 2004". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on May 20, 2015. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ "Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2004". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 1, 2015. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "Top 50 Global Best Selling Albums for 2004" (PDF). International Federation of the Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 30, 2009. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ^ "Ranking Venta Mayorista de Discos – Anual" (in Spanish). Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – End of Year Charts – Top 100 Albums 2005". ARIA Charts. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ^ "Jahreshitparade Alben 2005" (in German). austriancharts.at. Archived from the original on December 6, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 2005: Albums" (in Dutch). ultratop,be/nl. Archived from the original on September 30, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "Rapports Annuels 2005: Albums" (in French). ultratop,be/fr. Archived from the original on December 24, 2008. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 2005 – Alternatieve Albums" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ "Chart of the Year 2005". TOP20.dk. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Album 2005" (in Dutch). dutchcharts.nl. Archived from the original on June 18, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "Year End European Top 100 Albums Chart 2005 01 – 2005 52" (PDF). Billboard. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 15, 2006. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ The first list is the list of best-selling domestic albums of 2005 in Finland and the second is that of the best-selling foreign albums:

- "Myydyimmät kotimaiset albumit vuonna 2005" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- "Myydyimmät ulkomaiset albumit vuonna 2005" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ "Tops de l'Année – Top Albums 2005" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique. Archived from the original on July 15, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts 2005" (in German). Media Control Charts. Archived from the original on April 12, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Összesített album- és válogatáslemez-lista – eladási darabszám alapján – 2005" (in Hungarian). Magyar Hanglemezkiadók Szövetsége. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ "Best of Albums – 2005". Irish Recorded Music Association. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Classifica annuale 2005 (dal 03.01.2005 al 01.01.2006) – Album & Compilation" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ "年間 アルバムランキング 2005年度" [Oricon Year-end Albums Chart of 2005] (in Japanese). Oricon. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ "Top Selling Albums of 2005". Recorded Music NZ. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ^ "Årslista Album – År 2005" (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Swedish Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Årslista Album (inkl samlingar), 2005" (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ "Schweizer Jahreshitparade 2005" (in German). hitparade.ch. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 2005". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on May 31, 2015. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ "Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2005". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 12, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "Top 50 Global Best Selling Albums for 2005" (PDF). International Federation of the Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 30, 2009. Retrieved October 11, 2010.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – End of Year Charts – Top 100 Albums 2006". ARIA Charts. Archived from the original on January 27, 2014. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ^ "Jahreshitparade Alben 2006" (in German). austriancharts.at. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 2006 – Mid price" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ "Rapports Annuels 2006 – Mid price" (in French). Ultratop. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ "2006 Year-End European Albums". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ "Annual Chart — Year 2006 Top 50 Ξένων Αλμπουμ" (in Greek). IFPI Greece. Archived from the original on February 2, 2007. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 2006". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ "Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2006". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 1, 2015. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "Rapports Annuels 2007 – Mid price" (in French). Ultratop. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ "The Top 200 Artist Albums of 2007" (PDF). Chartwatch: 2007 Chart Booklet. Zobbel.de. p. 35. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ "Catalog Albums – Year-End 2015". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ "Catalog Albums – Year-End 2016". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ "Top Rock Albums – Year-End 2017". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 14, 2018. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ "ARIA – Decade-end Charts" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 17, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

- ^ "The Noughties' Official UK Albums Chart Top 100". Music Week. London. January 30, 2010. p. 19.

- ^ "Billboard – Decade-end Charts". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 14, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

- ^ "Official Top 100 biggest selling vinyl albums of the decade". Official Charts Company. December 14, 2019. Archived from the original on March 10, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ "Discos de Oro y Platino". Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2006 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Austrian album certifications – Green Day – American Idiot" (in German). IFPI Austria. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Ultratop − Goud en Platina – albums 2007". Ultratop. Hung Medien. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "No Brasil". O Globo (in Portuguese). May 29, 2006. ProQuest 334799919. Archived from the original on September 23, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2022 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Brazilian album certifications – Green Day – American Idiot" (in Portuguese). Pro-Música Brasil. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Green Day – American Idiot". Music Canada. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- ^ "Guld og platin i marts" (in Danish). IFPI Denmark. April 13, 2006. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2017.