Occupation of Western Armenia

Occupation of Western Armenia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1915–1918 | |||||||||

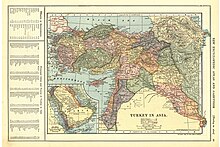

The area of Russian occupation as of September 1917 and administrative-territorial division of the regions of Turkey occupied by Russian troops during the First World War in 1916-1917. Some Western-Armenian regions (Berdaghrak\Yusufeli, Sper\Ispir, Tortum, Gaylget\Kelkit, Baberd\Bayburt and other) were included by Russians into Trebizon (Pontic) territorial division. | |||||||||

| Status | Military occupation | ||||||||

| Capital | Van (de facto) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Armenian Turkish Kurdish | ||||||||

| Religion | Armenian Apostolic Islam | ||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||

• Apr 1915 – Dec 1917 | Aram Manukian | ||||||||

• Dec 1917 – Mar 1918 | Tovmas Nazarbekian | ||||||||

• Mar 1918 – Apr 1918 | Andranik Ozanian | ||||||||

| Historical era | World War I | ||||||||

| April–May 1915 | |||||||||

| 8 March – 8 November 1917 | |||||||||

| 3 March 1918 | |||||||||

• Turkish recapture Erzurum | 12 March 1918 | ||||||||

• Turks recapture Van | 6 April 1918 | ||||||||

• Dissolved | April 1918 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| History of Armenia |

|---|

|

| Timeline • Origins • Etymology |

The occupation of Western Armenia by the Russian Empire during World War I began in 1915 and was formally ended by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. It was sometimes referred to as the Republic of Van[1][2][3] by Armenians. Aram Manukian of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation was the de facto head until July 1915.[4] It was briefly referred to as "Free Vaspurakan".[5] After a setback beginning in August 1915, it was re-established in June 1916. The region was allocated to Russia by the Allies in April 1916 under the Sazonov–Paléologue Agreement.

From December 1917, it was under Transcaucasian Commissariat, with Hakob Zavriev as the Commissar, and during the early stages of the establishment of First Republic of Armenia, it was included with other Armenian National Councils in a briefly unified Armenia.

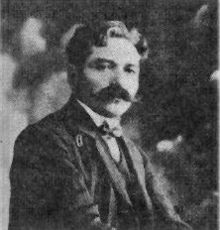

This provisional government relied on Armenian volunteer units, forming an administrative structure after the siege of Van around April 1915. Dominant representation was from the Armenian Revolutionary Federation. Aram Manukian, or "Aram of Van," was the administration's most famous governor.

Population distribution

[edit]During the siege of Van, there were between 67,792 (according to the 1914 Ottoman population estimates) and 185,000 Armenians (according to the Armenian Patriarch's 1912 estimate) in the Van Vilayet.[6] In the city of Van itself there were around 30,000 Armenians, but more Armenians from surrounding villages joined them during the Ottoman offensive.

History

[edit]

Formation, 1915

[edit]The conflict began on April 20, 1915, with Aram Manukian as the leader of the resistance, and it lasted for two months. In May, the Armenian battalions and Russian regulars entered the city and drove the Ottoman army out of Van.[7]

Departure from Van

[edit]July was the second month of self-government under the leadership of Manoukian. Then, the conflict turned against the Armenians. The Ottoman Army, under Pasha Kerim, launched a counterattack in the Lake Van area and defeated the Russians at the Battle of Malazgirt.

The Russians retreated eastward. There were as many as 250,000 Armenians crowded into the city of Van.[8] These people were the escapees from the deportations established by the Tehcir Law; included were also many who broke away from the deportation columns, as they passed the vicinity on their way to Mosul.[8] Armenians from this region retreated to the Russian frontier.[9]

During the counterattack, Manoukian and Sampson Aroutiounian, president of the Armenian National Council of Tbilisi, helped refugees from the region to reach Echmiadzin.[10] As a result of famine and fatigue, many refugees suffered from diseases, especially dysentery.[10] On 29 December 1915, the Dragoman of the Vice-Consulate at Van, according to the Armenian Bishop of Erevan and other sources, was able to procure the Caucasus refugees from the region.[11]

| Origin | 13 August Echmiadzin refugees[10] |

29 December Caucasus refugees[11] |

|---|---|---|

| Van and surrounding region | 203,000[10] | 105,000[11] |

| Malazgirt (Muş Province) | 60,000[10] | 20,038 [11] |

| Regional Total | 250,000[9] (from Narrative of Van) |

Return to Van

[edit]During the winter of 1915, the Ottoman forces retreated once again, which enabled Aram Manukian to return to Van and re-establish his post.[11] The governor declared strict measures to prevent pillage and destruction of property in December 1915. Some threshing machines and flour mills resumed work in the district so that bakeries could reopen, and the restoration of buildings commenced in some streets.[11]

| 29 December Returned refugees[11] | |

|---|---|

| City of Van | 6,000 |

Expansion, 1916

[edit]At the turn of 1916, Armenian refugees returned to their homes, but the Russian government raised barriers in prevention.[12] During 1916–17 about 8,000 to 10,000 Armenians were permitted to inhabit Van.

One report said:

"Men are going in large numbers; caravans of those returning to the fatherland enter via Iğdır. Most of the refugees in the Erevan province returned to Van."[13]

| 1 March Returned refugees | Expected[13] | |

|---|---|---|

| Van district | 12,000 | between 20,000 and 30,000 |

The Near East relief brought relief to the victims of the war and organized in 1916 a Children's Home in Van. Children's Home helped children to learn reading and writing and supplied them nice clothes.[14] Near East relief worked in Syria and "several hundred thousand" during the Caucasus Campaign.[15]

Russian plans

[edit]In April 1915, Nikolai Yudenich reported the following to Count Illarion Ivanovich Vorontsov-Dashkov:

The Armenians intend to occupy by means of their refugees the lands left by the Kurds and Turks, in order to benefit from that territory. I consider this intention unacceptable, because after the war, it will be difficult to reclaim those lands sequestered by the Armenians or to prove that the seized property does not belong to them, as was the case after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78. I consider it very desirable to populate the border regions with a Russian element... with colonists from the Kuban and Don and in that way to form a Cossack region along the border.[16]

The agricultural possibilities located off the Black Sea coastal districts and the upper reaches of the Euphrates were considered suitable for Russian colonists.[17] Following the April 1916 Sazonov–Paléologue Agreement, the Rules for the Temporary Administration of Turkish Areas occupied by the Right of War was signed on June 18, 1916, instructing a governorship under the established system of Aram Manukian.

|

|

|

The settlement, 1917

[edit]Approximately 150,000 Armenians relocated to Erzurum Vilayet, Bitlis Vilayet, Mush and Van Vilayet in 1917.[19]

| Vilayet | City | Refugees resettled |

|---|---|---|

| Erzurum | Gharakalisa | 35,000 |

| Khnus | 32,500 | |

| Erzrum | 22,000 | |

| Bayazit | 10,000 | |

| Mamakhatun | 9,000 | |

| Yerznka | 7,000 | |

| Van | Van | 27,600 |

| Trebizond | Trebizond | 1,500 |

| TOTAL | 144,600 | |

Special Transcaucasus Committee

[edit]The Viceroyalty of the Caucasus was abolished by the Russian Provisional Government on March 18, 1917, and all authority, except in the zone of the active army, was entrusted to the civil administrative body called the Special Transcaucasian Committee, or Ozakom. Hakob Zavriev was instrumental in having Ozakom issue a decree about the administration of the occupied territories. This region was officially identified as "the land of Western Armenia" and transferred to a civilian rule under Zavriev, who oversaw districts Trebizon, Erzurum, Bitlis, and Van.[21]

National frontline

[edit]The Russian army in the Caucasus was organized along national and ethnic lines, such as the Armenian volunteer units and Russian Caucasus Army on the eve of 1917.[22] However, the Russian Caucasus Army disintegrated, leaving Armenian soldiers to become the only defenders against the Ottoman Army.[23]

The front line had three main divisions, led respectively by Movses Silikyan, Andranik Ozanian and Mikhail Areshian. Armenian partisan guerrilla detachments accompanied these main units. The Ottomans outnumbered the Armenians three to one on a frontline 480 kilometres (300 mi) long, with high mountain areas and passes.

Retreat, 1918

[edit]The chairman of the Van Relief Committee (Near East Relief) was Kostin Hambartsumian, who, taking into consideration the general political situation, conveyed the one thousand five hundred orphans of Children's Home of Van to Gyumri in 1917.

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, March 1918

[edit]

A new border was drawn by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed between Russian SFSR and the Ottoman Empire on March 3, 1918. The treaty assigned the Van Vilayet alongside the Kars Vilayet, Ardahan, and Batum regions to the Ottoman Empire. The treaty also stipulated that Transcaucasia was to be declared independent.

The Resistance, March 1918

[edit]The Armenian Congress of Eastern Armenians (ACEA) representatives on the Duma joined their colleagues in declaring independence of the Transcaucasus from Russia.

On April 5, head of the Transcaucasian delegation Akakii Chkhenli accepted the Treaty as a basis for negotiation and wired the governing bodies, urging them to accept this position.[24] The mood prevailing in Tiflis was very different; the treaty did not create a united block. Armenia acknowledged the existence of a state of war with the Ottoman Empire.[24] This short-lived Transcaucasian Federation broke up. Once they were free from Russian control, the ACEA declared the inauguration of the Democratic Republic of Armenia. ACEA did not recognize the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, and the Ottoman Empire was opposed to the Democratic Republic of Armenia. The ACEA devised policies to direct the war effort as well as the relief and repatriation of refugees, passing a law organizing the defense of the Caucasus against the Ottoman Empire, using supplies and munitions left by the Russian army. The Armenian Congress also selected a 15-member permanent executive committee, known as the Armenian National Council. The chairman of this committee was Avetis Aharonyan, who declared that the Administration of Western Armenia was part of the Democratic Republic of Armenia.

The Ottoman Empire's War Minister, Enver Pasha, sent the Third Army to Armenia. Under heavy pressure from the combined forces of the Ottoman army and the Kurdish irregulars, the Armenian Republic was forced to withdraw from Erzincan to Erzurum. The Battle of Sardarapat, May 22–26, 1918, proved that General Movses Silikyan could force an Ottoman retreat. Further southeast, in Van, the Armenians resisted the Ottoman army until April 1918, while in Van the Armenians were forced to evacuate and withdraw to Persia. Richard G. Hovannisian explains the conditions of their resistance during March 1918:

"In the summer of 1918, the Armenian national councils reluctantly transferred from Tiflis to Yerevan, to take over the leadership of the republic from the popular dictator Aram Manukian and the renowned military commander Drastamat Kanayan. It then began the daunting process of establishing a national administrative machinery in an isolated and landlocked misery. This was not the autonomy or independence which Armenian intellectuals had dreamed of and for which a generation of youth had been sacrificed. Yet, as it happened, it was here that the Armenian people were destined to continue [their] national existence."[25]

— R.G. Hovannisian

The Azerbaijani Tatars sided with the Ottoman Empire and seized the lines of communication, cutting off the Armenian National Councils in Baku and Erevan from the National Council in Tbilisi. The British sent a small military force under the command of Gen. Lionel Charles Dunsterville into Baku, arriving on August 4, 1918.

On October 30, 1918, the Ottoman Empire signed the Armistice of Mudros, and military activity in the region ceased. Enver Pasha's movement disintegrated with the armistice.[26]

Recognition Efforts

[edit]

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, between the Ottoman Empire and Russian SFSR, included the establishment of Armenia in Russian Armenia. The Administration for Western Armenia had a setback with the Treaty of Batum, forcing the Armenian borders to be pushed deeper into Russian Armenia.

During the Conference of London, David Lloyd George encouraged American President Woodrow Wilson to accept a mandate for Anatolia, particularly with the support of the Armenian diaspora, for the provinces claimed by the Administration of Western Armenia during its largest occupation in 1916. "Wilsonian Armenia" became part of the Treaty of Sèvres.

The realities on the ground, however, were slightly different. The idea was blocked by both the Treaty of Alexandropol and the Treaty of Kars. The Treaty of Sèvres was superseded by the Treaty of Lausanne, and the fight for the "Administration for Western Armenia" was dropped off the table.

As a continuation of the initial goal, the creation of a "free, independent, and united" Armenia including all the territories designated as Wilsonian Armenia by the Treaty of Sèvres — as well as the regions of Artsakh and Javakhk— was the main goal of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation.

Administration

[edit]Governors

[edit]- Jun 1916 – Dec 1917 Aram Manukian (interim)

- Dec 1917 – Mar 1918 Tovmas Nazarbekian

- Mar 1918 – Apr 1918 Andranik Ozanian

Civil affairs

[edit]- May 1917 – Dec 1917 Hakob Zavriev

Civil Commissioner

[edit]- Dec 1917 – Apr 7, 1918 Drastamat Kanayan

Timeline

[edit]- April 19, 1915: Fire in the powder stores of the Van armoury.

- April 20, 1915: Armenians in the city of Van, the countryside, and small towns begin a local uprising.

- April 24, 1915: Ottoman governor asks permission to move the Muslim civilian population to the west.

- May 2, 1915: Ottoman Army moves close to Van, but withdraws because of the presence of the Russian Army.

- May 3, 1915: Russian Army enters Van.

- August 16, 1915: Ottoman Army besieges Van; Battle of Van.

- September 1915: Ottoman Army is forced out by Russians.

- April 1916: Sazonov–Paléologue Agreement

- August 1916: Ottoman Army moves to the west of the region (Mush and Bitlis), but is forced out within a month.

- February 1917: Russian units disintegrate. Armenian volunteer units keep formation.

- September 1917: The Armenian Congress of Eastern Armenia merges Armenian volunteer units into a single militia under its control.

- February 10, 1918: The Duma of the Transcaucasus convenes.

- February 24, 1918: The Duma of the Transcaucasus declares the region to be an independent, democratic, federative republic.

- March 3, 1918: The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk gives Kars, Ardahan, and Batum regions to the Ottoman Empire.

- March 4, 1918: The Administration for Western Armenia condemns the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

- March 9, 1918: The Administration for Western Armenia presents its position to the Ottoman Empire.

- May 22, 1918: Battle of Sardarapat; Armenian militia fight against the Ottoman Empire.

- May 28, 1918: The Armenian Congress of Eastern Armenia declares the formation of the Democratic Republic of Armenia and its independence from the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic.

- August 4, 1918: General Lionel Charles Dunsterville leads a British expeditionary force into Baku and becomes the city's military governor.

- October 30, 1918: The Ottoman Empire signs the Armistice of Mudros, agreeing to leave the Transcaucasus.

References

[edit]- ^ Herrera, Hayden (2005). Arshile Gorky: His Life and Work. Macmillan. p. 78. ISBN 9781466817081.

- ^ Aya, Şükrü Server (2008). The genocide of truth. Eminönü, Istanbul: Istanbul Commerce University Publications. p. 296. ISBN 9789756516249.

- ^ Onnig Mukhitarian, Haig Gossoian (1980). The Defense of Van, Parts 1-2. Central Executive General Society of Vasbouragan. p. 125.

- ^ The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times: Foreign Dominion to Statehood, edited by Richard G. Hovannisian.

- ^ Robert-Jan Dwork Holocaust: A History by Deborah and van Pelt, p 38

- ^ Viscount Bryce, James (1916). The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire 1915-1916. London: T. Fisher Unwin Ltd.

- ^ Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Hayots Badmoutioun (Armenian History) (in Armenian). Hradaragutiun Azkayin Oosoomnagan Khorhoortee, Athens. pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire" pp.314-316,

- ^ a b A.S. Safrastian "Narrative of Van 1915" Journal Ararat, London, January, 1916

- ^ a b c d e Arnold Toynbee, The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, 1915-1916: Documents Presented to Viscount, p. 226.

- ^ a b c d e f g Toynbee, Arnold Joseph. "Memorandum on the Condition of Armenian Refugees in the Caucasus: ...". The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, 1915-1916: Documents Presented to Viscount.

- ^ Garegin Pasdermadjian, Aram Torossian, "Why Armenia Should be Free: Armenia's Rôle in the Present War" page 31

- ^ a b Arnold Toynbee, The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, 1915-1916: Documents Presented to Viscount, "Repatriation of Refugees: Letter, dated Erevan, March, 1916."

- ^ Memories of Eyewitness-Survivors of the Armenian Genocide: Ghazar Ghazar Gevorgian's Testimony. Born in 1907, Van, Armenian valley, Hndstan village

- ^ Jay Murray Winter "America and the Armenian Genocide of 1915" p.193

- ^ Gabriel Lazian (1946), "Hayastan ev Hai Dare" Cairo, Tchalkhouchian, pages 54-55.

- ^ Ashot Hovhannisian, from "Hayastani avtonomian ev Antantan: Vaveragrer imperialistakan paterazmi shrdjanits (Erevan, 1926), pages 77–79

- ^ Morgenthau, Henry (1917). Ambassador Morgenthau's Story. Doubleday, Page & Company.

- ^ The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times: Foreign Dominion to Statehood, Richard G. Hovannisian, ed.

- ^ Harutyunyan, Babken (2019). Atlas of the Armenian Genocide. Vardan Mkhitaryan. Erevan. p. 47. ISBN 978-9939-0-2999-3. OCLC 1256558984.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Richard G. Hovannisian, The Armenian People From Ancient To Modern Times. page 284

- ^ David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, Reforming the Tsar's Army: Military Innovation in Imperial Russia from Peter the Great, p. 52

- ^ The Armenians: Past and Present in the Making of National Identity, ed. Edmund Herzig, Marina Kurkchiyan, p.96

- ^ a b Richard Hovannisian "The Armenian people from ancient to modern times" Pages 292-293

- ^ The Armenians: Past and Present in the Making of National Identity, p. 98, edited by Edmund Herzig, Marina Kurkchiyan

- ^ Fromkin, David (1989), A Peace to End All Peace, 'The parting of the ways'. (Avon Books).

External links

[edit]- States and territories disestablished in 1918

- States and territories established in 1915

- Subdivisions of the Ottoman Empire

- Politics of the Ottoman Empire

- Erzurum vilayet

- Bitlis vilayet

- Trebizond vilayet

- Van vilayet

- Provisional governments

- 1910s in Armenia

- Western Armenia

- Invasions by Russia

- Russian Empire in World War I

- Russian military occupations

- Ottoman Empire in World War I