2014 Isla Vista killings

It has been suggested that this article should be split into a new article titled Elliot Rodger. (discuss) (April 2024) |

| 2014 Isla Vista killings | |

|---|---|

| Location | Isla Vista, California, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 34°24′43″N 119°51′32″W / 34.412°N 119.859°W |

| Date | May 23, 2014 9:27 – 9:35 p.m. (UTC−8:00) |

| Target | Students of the University of California, Santa Barbara, roommates |

Attack type | |

| Weapons |

|

| Deaths | 7 (3 by stabbing; 4 by gunfire, including the perpetrator) |

| Injured | 14 (7 by gunfire, 7 struck by motor vehicle) |

| Perpetrator | Elliot Rodger |

| Motive | Misogynist terrorism, revenge for sexual and social rejection, incel ideology |

The 2014 Isla Vista killings were two misogynistic terror attacks in Isla Vista, California. On the evening of Friday, May 23, 22-year-old Elliot Rodger killed six people and injured fourteen others by gunshot, stabbing and vehicle ramming near the campus of the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), before fatally shooting himself.[1][2][3][4][5]

Rodger stabbed his two roommates and their friend to death in his apartment, ambushing and killing them separately as they arrived. About three hours later, he drove to a sorority house and, after failing to get inside, shot three women outside, two of whom died. He next drove past a nearby deli and shot and killed a man who was inside. He then drove around Isla Vista, shooting and wounding several pedestrians from his car and striking others with his car. He exchanged gunfire with police twice and was injured in the hip. After his car crashed into a parked vehicle, he was found dead inside with a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head.

Before driving to the sorority house, Rodger uploaded a video to YouTube titled "Elliot Rodger's Retribution", in which he outlined his planned attack and his motives. He explained that he wanted to punish women for rejecting him, and sexually active men because he envied them. He also emailed a lengthy autobiographical manuscript to friends, his therapist and family members; the document appeared on the Internet and became widely known as his manifesto. In it, he described his childhood, family conflicts, frustration over his inability to find a girlfriend, his hatred of women, his contempt for couples (particularly interracial couples) and his plans for what he described as "retribution". In February 2020, the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism at the Hague retroactively described the killings as an act of misogynist terrorism.[6] The US Secret Service describes it as "misogynistic extremism".[7]

Attacks

On May 23, 2014, 22-year-old Elliot Rodger, carrying 6- and 8-inch "SRK" and nine-inch boar hunting knife, first attacked his roommate, 20-year-old Weihan "David" Wang, when Wang came back to their apartment. Wang tried to defend himself but was stabbed 15 times. Rodger then attacked his other roommate, 20-year-old Cheng Yuan "James" Hong, who showed up later, stabbing him 25 times as Hong tried to protect himself. Rodger dragged Wang and Hong's bodies in a bedroom and hid them in a blanket, towel, and clothing. The last person to arrive at the apartment was 19-year-old George Chen, a friend of Wang and Hong. Chen was also attacked by Rodger and was stabbed 94 times as he attempted to defend himself. Chen's body was left in a bathroom.[8][9] Blood on the walls and blood-soaked paper towels showed that Rodger tried to clean the apartment's hallways and hide signs of the earlier stabbings as each victim entered the apartment.[8][9][10]

After killing the three men, within a three-hour time frame, Rodger changed out of his clothes that were drenched in blood and then went to Starbucks, where he bought a triple-vanilla latte. Less than two hours after his Starbucks visit, he uploaded a video on YouTube called "Elliot Rodger's Retribution" and emailed a 137-page document called My Twisted World to 34 people, including his parents, friends, and therapists.[11] His mother, Li Chin Rodger, was alerted by a call from her son's therapist Gavin Linderman to check an email he sent. After seeing his manifesto and finding the "Retribution" video online, she and Rodger's father, Peter Rodger, rushed towards the University while contacting the police.[12][13] Rodger first went to the Alpha Phi sorority house, where he tried to get inside by knocking on the door for three minutes.[8] Unable to enter, he returned to his car and, from an open window, shot at three members of the Delta Delta Delta sorority who were walking back to their sorority house. The victims were 19-year-old Veronika Weiss, 22-year-old Katherine Cooper, and a 20-year-old woman.[8][14][15][16] Weiss and Cooper died from their injuries, while the 20-year-old woman, bleeding and calling her mother, was helped by a deputy who put pressure to her wounds. A bystander continued to give first aid to the woman when the deputy left to join the chase for Rodger.[8][16]

After leaving the sorority house, Rodger made a three-point turn in a driveway on Pardall Road. As he drove past a coffee shop on Pardall, he fired a shot into it, but the shop was closed.[16] Next, he went to the IV Deli Mart, where he began shooting at people nearby. As 20-year-old Christopher Michaels-Martinez looked to see Rodger's car from the store's entrance, he was shot in the chest,[17] causing injuries to his liver and right ventricle of his heart.[18] Michaels-Martinez entered the deli and fell to the floor.[16] A 19-year-old woman attempted CPR but Michaels-Martinez had immediately died from his injuries.[18] Rodger fired more shots into the deli, breaking windows while people inside tried to find cover.[8][16][19] Rodger then continued driving, hitting a man with his car, causing him to be thrown into the air.[16] Driving on the wrong side of the street, he hit another pedestrian and fired at two people on the sidewalk but missed them. He shot a couple leaving a pizzeria and a female cyclist. After turning onto several streets, Rodger exchanged gunfire with a sheriff's deputy and hit two pedestrians. Rodger shot and injured three people on Sabado Tarde Street, hit a skateboarder and two cyclists with his car, and then shot two other men at another intersection.[20]

Near the intersection of El Embarcadero and Sabado Tarde, he had a shootout with three sheriff's deputies and got shot in the hip.[21] Trying to escape the police, he turned onto several streets, hitting another cyclist who tumbled and damaged the car's windshield. Rodger eventually crashed his car into several other vehicles.[22] As police surrounded the car, they mistakenly handcuffed the cyclist, thinking he might be a second suspect. They soon realized the cyclist was actually a victim, not involved in the attacks, and provided him with medical care.[23] The police looked in the car and found Rodger dead from a self-inflected gunshot wound to the head.[22] In Rodger's car, the police found a Glock 34 handgun, two SIG Sauer P226 handguns, 500 additional rounds of live ammunition, and two knives. The entire shooting spree lasted for eight minutes, during which Rodger fired about 55 9mm rounds. The attacks resulted in seven people's deaths and 14 others being injured.[16]

Items found in car

Inside Rodger's car, authorities found a Glock 34 handgun, two SIG Sauer P226 handguns, over 500 additional rounds of live ammunition, and the two knives he used to kill his two roommates and their friend. The entire shooting spree unfolded within eight minutes, during which Rodger discharged approximately 55 9mm rounds.[16] During the shootings, Rodger used only one of the three pistols, the Sig Sauer P226, which was discovered on the driver's seat of his car.[24]

Victims killed

Rodger's rampage resulted in the deaths of six people, all University of California, Santa Barbara students, with 14 others sustaining injuries.[25]

- 20-year-old Weihan "David" Wang (stabbed to death)

- 20-year-old Cheng Yuan "James" Hong (stabbed to death)

- 19-year-old George Chen (stabbed to death)

- 22-year-old Katherine "Katie" Breanne Cooper (shot to death)

- 19-year-old Veronika Elizabeth Weiss (shot to death)

- 20-year-old Christopher Ross Michaels-Martinez (shot to death)

Apartment search

Following the attacks, law enforcement obtained a search warrant and conducted a protective sweep of Rodger's apartment. After removing a window screen, authorities looked inside and found Chen's body lying in a fetal position on the bathroom floor.[24][26] They breached the apartment and also found the bodies of Hong and Wang in their bedroom. When they searched Rodger's room, they found it to be a mess, finding pharmacy documents for prescriptions, two gun cleaning kits, Monster Energy drinks, lottery tickets, a copy of The Art of Seduction, various video games, and a Starbucks coffee cup. Additionally, police found a folding knife, a "zombie killer" knife with a 10-inch blade, an 18-inch blade machete, a sledgehammer, and multiple other knives. They also found a hand-drawn picture of something getting stabbed and a printed copy of Rodger's 137-page manifesto. His laptop was found open to YouTube, displaying his recently uploaded "Retribution" video.[8][27] A handwritten journal was left open to an entry dated May 23, 2014, reading:

I had to tear some pages out because I feared my intentions would be discovered. I taped them back together as fast as I could. This is it. In one hour I will have my revenge on this cruel world. I HATE YOU ALLLL! DIE.[16]

Aftermath

Students and community members gathered at Anisq'Oyo Park in Isla Vista on the evening of May 24 for a candlelight memorial to remember the victims.[28][29] 20,000 people attended a memorial service at UCSB's Harder Stadium on May 27.[30] On May 23, 2015, the first anniversary of the attacks, hundreds of people gathered at UCSB for a candlelight vigil commemorating the six slain victims. The mother of George Chen made a speech at the event.[31]

Following the attacks, some on Twitter used the #NotAllMen hashtag to express that not all men are misogynistic and not all men commit murder. Others criticized use of this hashtag, as it was considered to derail from discussion of the issue of violence against women.[32][33][34] In response to #NotAllMen, users @anniecardi and @gildedspine created the hashtag #YesAllWomen on May 24 to express the fact that all women experience misogyny and sexism.[35][33][36][37]

Perpetrator

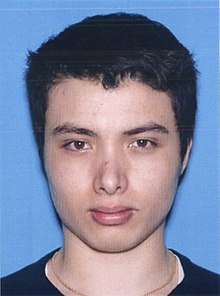

Elliot Rodger | |

|---|---|

Driver's license photo of Rodger | |

| Born | Elliot Oliver Robertson Rodger July 24, 1991 |

| Died | May 23, 2014 (aged 22) Isla Vista, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Suicide by gunshot |

| Nationality |

|

| Other names | |

| Occupation | Student |

| Movement | Incels |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives | George Rodger (grandfather) |

Elliot Oliver Robertson Rodger (July 24, 1991 – May 23, 2014) was an English-American former college student, and the sole perpetrator of the 2014 Isla Vista killings.

Early life

Born in London, England, he moved to the United States with his parents at age five.[41] He was raised in Los Angeles. His father is the British filmmaker Peter Rodger, and his paternal grandfather is the photo-journalist George Rodger.[5][42] His mother is a Malaysian Chinese nurse who served as a first aid practitioner and research assistant on several major film productions.[43][44][45][46] A younger sister was born before his parents divorced. After Peter remarried, he and his second wife, Soumaya Akaaboune,[47] a Moroccan actress with whom Elliot had a strained relationship,[48] had a son together, Elliot's half-brother.

Rodger attended Crespi Carmelite High School, an all-boys Catholic school in Encino, Los Angeles, and then Taft High School in Woodland Hills, which he attended for only a week due to severe bullying.[49] He last attended Independence Continuation High School in Lake Balboa from where he graduated in 2009.[49] Rodger briefly enrolled in Los Angeles Pierce College and Moorpark College before transferring to Santa Barbara City College in 2011.[50] Thereafter, he resided in Isla Vista.[51] After his attack, the school said he had not taken any classes since 2012.[52]

Mental health and social problems

According to his family's attorney and a family friend, Rodger had seen multiple therapists since he was eight years old,[52] but the attorney said he had never been formally diagnosed with a mental illness.[53] He was diagnosed with pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified, an autism spectrum disorder, in 2007.[50]

By the ninth grade, Rodger was "increasingly bullied", and wrote later that he "cried by [himself] at school every day";[54] at this time he developed an addiction to the online game World of Warcraft, which dominated his life for most of his teenage years, and briefly into his 20s. At Crespi Carmelite High he was bullied; in one incident his head was taped to a desk while he was asleep.[3][55] According to Rodger, in 2012, "the one friend [he] had in the whole world who truly understood [him] ... said he didn't want to be friends anymore" without offering any reason.[54] Rodger had a YouTube account, and a blog titled "Elliot Rodger's Official Blog", through which he expressed loneliness and rejection. He wrote that he had been prescribed risperidone but refused to take it, stating, "After researching this medication, I found that it was the absolute wrong thing for me to take."[56]

After turning 18, Rodger began rejecting mental health care and became increasingly isolated. He said that he was unable to make friends, although acquaintances said that he rebuffed their attempts to be friendly.[57] A family friend, Dale Launer, said that he counseled Rodger on approaching women, but that Rodger did not follow the advice. Launer also commented that when he met Rodger at eight or nine, "I could see then that there was something wrong with him ... looking back now he strikes me as someone who was broken from the moment of conception."[58]

Incidents with law enforcement

On July 20, 2013, Rodger, wanting to lose his virginity days before his 22nd birthday, drank vodka to become drunk. He went to a party hoping to talk to girls. Unable to talk to girls, Rodger became angry and climbed onto a 10-foot ledge and pretended to shoot people at the party with his finger. He then tried to push several women off the ledge, but a group of men stopped him by pushing him off instead, causing him to break his ankle.[59] After the fall, Rodger went back toward the party to look for his sunglasses but was so drunk that he ended up getting into another altercation in front of a different house. The day after, two sheriff's deputies visited him in the hospital to ask about the fights. Rodger told them he had been pushed off the ledge after calling someone "ugly" and claimed that after the fight, he walked to a nearby front yard and sat down in a chair. He stated that he was attacked by about 10 men who kicked and punched him. Rodger was hurt on his arms, elbows, hands, face, and left ankle. He told police he did not know why he was attacked or called names.[59] He also said he did not call the police because he did not know who to call. A deputy noted that Rodger was too "timid" and "shy" to say what really happened. A witness said a man like Rodger began the fight by trying to push two women off a ledge. They didn't fall, but Rodger tried to push two more before he jumped off the ledge and ran. The witness noted Rodger was alone, acted oddly, and wasn't talking to anyone at the party.[60] After arriving at his apartment, a neighbor observed Rodger returning home in tears, swearing to kill those who attacked him and contemplated suicide. Rodger disclosed in his manifesto that this event was the decisive moment that propelled him to finalize his plans for the attack. The sheriff's office concluded Rodger had started the fight, and the investigation was closed without further action. They did not arrest Rodger or interrogate him further.[61][59]

On January 15, 2014, Rodger had a fight with Hong after accusing him of stealing three candles worth $22. Rodger placed Hong under a citizen's arrest. When police arrived Hong explained he thought Rodger stole his items, including a rice bowl. Rodger denied the claims. Refusing to return the candles, Hong was arrested and later faced a petty theft charge, for which he was fined and released. Following Hong's murder, the District Attorney, Joyce E. Dudley, filed a motion to dismiss the theft charge, which was subsequently granted.[60][62] On April 30, 2014, Rodger's mother, worried because she hadn't heard from her son in four days and alarmed by the videos he had posted online, reached out to his therapist.[63][64] The therapist then contacted a mental health professional, who requested a welfare check on Rodger. Responding to the request, four sheriff's deputies, a university police officer, and a dispatcher in training visited Rodger's apartment.[63][65] Rodger explained that the videos were his way of expressing his social difficulties in Isla Vista.[63] The officers concluded that Rodger did not pose an immediate risk to himself or others, making him ineligible for involuntary hold.[66] Before they left, a deputy called Rodger's mother to update her and handed the phone to Rodger, who reassured her he was alright and would call her later. The deputies also provided Rodger with information on local support services.[63][67] In his manifesto, Rodger mentioned that the visit from the deputies forced him to remove most of his videos from YouTube in case of being caught. However, in the week leading up to the attacks, he re-posted them.[65]

Manifesto

Rodger created and emailed a 137-page 107,000-word manifesto called My Twisted World: The Story of Elliot Rodger to 34 people, including his parents, former teachers, childhood friends, and therapists.[11] Rodger's manifesto starts as a story of his life, where he expresses his anger towards women and his views on why he felt treated unfairly by life.[68][69] As the manifesto progresses, Rodger details his plan for his "Day of Retribution," divided into three parts. The first part involved killing his roommates and any other people he could bring to his apartment.[70][71] The second part, which he called the "War on Women," was where he intended to kill as many women as he could inside the Alpha Phi sorority house. In the final part, Rodger planned to drive around Isla Vista, shooting and hitting as many people with his car.[72][73] Rodger's father was aware that he had been writing something, but Rodger refused to show him it. On a hike they took together before the attacks, Rodger's father expressed interest on what he was writing and asked if he could send it to him. Rodger brushed off the request, assuring him that he would share it in due time.[53]

Online history

Rodger posted about 22 videos on YouTube, expressing frustrations over his inability to get a girlfriend and his views on life, with titles like “Why do girls hate me so much?”, “Life is so unfair because girls don't want me”, and “My reaction to seeing a young couple at the beach, Envy”.[74][75] Other videos included Rodger driving while listening to music. Shortly before the attacks, one of his videos caught attention on Reddit's “cringe” forum, where a user commented that Rodger gave off a "strong Patrick Bateman vibe," suggesting he seemed like a serial killer.[76] Minutes before starting his attack on Isla Vista, Rodger uploaded his "Retribution" video to YouTube. In the video, Rodger is seen sitting in his BMW during a sunset, reciting scripted lines and letting out fake laughs.[74] Rodger explained in the video that he was frustrated that he was still a virgin at 22 and wanting to be loved by a woman:

Well, this is my last video, it has all had to come to this. Tomorrow is the day of retribution, the day in which I will have my revenge against humanity, against all of you. For the last eight years of my life, ever since I hit puberty, I've been forced to endure an existence of loneliness, rejection and unfulfilled desires all because girls have never been attracted to me. Girls gave their affection, and sex and love to other men but never to me. I'm 22 years old and I'm still a virgin. I've never even kissed a girl. I've been through college for two and a half years, more than that actually, and I'm still a virgin. It has been very torturous. College is the time when everyone experiences those things such as sex and fun and pleasure. Within those years, I've had to rot in loneliness. It's not fair. You girls have never been attracted to me. I don't know why you girls aren't attracted to me, but I will punish you all for it. It's an injustice, a crime, because… I don't know what you don't see in me. I'm the perfect guy and yet you throw yourselves at these obnoxious men instead of me, the supreme gentleman. I will punish all of you for it. On the day of retribution I'm going to enter the hottest sorority house of UCSB. And I will slaughter every spoiled, stuck-up, blond slut I see inside there. All those girls I've desired so much, they would have all rejected me and looked down upon me as an inferior man if I ever made a sexual advance towards them while they throw themselves at these obnoxious brutes. I'll take great pleasure in slaughtering all of you.[77][78][79]

Rodger often visited online forums like ForeverAlone and PUAHate, where men who felt unsuccessful with women shared their frustrations, criticized each other, spoke negatively about women, and criticized pick-up artists.[80] On these forums, Rodger and others made statements against women and Rodger described himself as an "Incel," which stands for involuntarily celibate. This term is used in an online community where members talk about their struggles to find a romantic or sexual partner.[81] Rodger expressed racist views in his posts, including mocking an Asian man trying to date a white girl and stating it was “rage-inducing” to see a “black guy chilling with 4 hot white girls.”[9] Rodger's online activities included numerous searches related to Nazis, such as researching Joseph Goebbels and Heinrich Himmler, and looking up topics like "Did Adolf Hitler have a girlfriend" and "Nazi anime."[8][82] He also searched for information on "modern torture devices" and "Spanish Inquisition torture devices."[83] In the days leading up to the attack, he visited websites like anxietyzone.com and bodybuilding.com.[8] On the day of his attacks, Rodger looked up pornography and searched online for "quiet silent kill with a knife" and "how to kill someone with a knife," indicating he was searching on how to kill his two roommates and their friend before they arrived.[8][84]

Preparations

In February 2012, after being unable to find a girlfriend, Rodger mentioned in his manifesto that the "Day of Retribution" became a possibility.[61] He became fixated on winning the lottery as he believed it was the only way for him to lose his virginity due to the wealth he would acquire.[85] By June 2012, Rodger wrote that winning The Mega Millions lottery jackpot was the only way in which he would not carry out his planned "Day of Retribution." When he did not win the jackpot in September 2012, he visited a gun range in Oxnard, California. Starting in November 2012, Rodger made several trips from California to Arizona to buy tickets for the Powerball jackpot, but after failing to win, he began to actively plan his attack.[61] His first purchase was a Glock 34 semiautomatic pistol, which he bought $700 in December 2012. In spring 2013, he bought an Sig Sauer P226 for $1,100. He saved up $5,000 for the supplies needed for the attack, and was able to buy another Sig Sauer P226 in 2014.[61][86] He funded his weapon purchases with money he had saved from gifts from his grandparents and the $500 monthly allowance his father sent him.[85]

Further planning

In August 2013, Rodger decided to delay his planned attack until Spring 2014. By January 2014, he had chosen April 26, 2014, as the new date for his attack.[61] Rodger initially planned to carry out his attack on Halloween in 2013 but decided against it, thinking there would be too many police officers around at that time.[87] He also thought about launching his attack on Valentine's Day and during Deltopia, a spring break event that attracts thousands of young people to Isla Vista in early April. However, he decided against these dates too, concerned about the high presence of police and realizing he needed more time to prepare for the attack.[61] In his manifesto, Rodger expressed a desire to kill his six-year-old stepbrother, fearing he would grow up to be more popular with girls than him.[88][89] He also wanted to kill his stepmother because he disliked her.[90] Rodger planned to carry out these murders while his father was away on a business trip, concerned he might have to kill his father too if his plans were discovered.[90][91] However, on April 24, Rodger fell ill with a cold, which led him to postpone his attack to May 24, 2014.[61][87]

Responses

Gun control and mental health

The attacks renewed calls for gun control and improvements in the American health care system, with Connecticut Senator Richard Blumenthal saying,

A year and half ago it seemed like we were on the verge of, potentially, legislation that would stop the madness and end the insanity that has killed too many young people, thousands, tens of thousands since Sandy Hook. I hope, I really, sincerely hope that this tragedy, this unimaginable, unspeakable tragedy, will provide impetus to bring back measures that would keep guns out of the hands of dangerous people who are severely troubled or deranged like this young man was.[92][93]

California Senator Dianne Feinstein blamed the National Rifle Association of America's "stranglehold" on gun laws for the attack and said "shame on us" in Congress for failing to do something about it.[94] Timothy F. Murphy, a Representative from Pennsylvania and a clinical psychologist, said his bipartisan mental health overhaul would be a solution and urged Congress to pass it.[95]

Richard Martinez, the father of victim Christopher Michaels-Martinez, gave a speech in which he placed the blame of the attacks on "craven, irresponsible" politicians and the National Rifle Association.[96][97] Martinez later urged the public to join him in "demanding immediate action" from members of Congress regarding gun control. He also expressed his sympathy towards Rodger's parents.[98]

Doris A. Fuller, the executive director of the Treatment Advocacy Center, said that California law permitted emergency psychiatric evaluations of potentially dangerous individuals through provisions, but such actions were never enabled during the initial police investigation of Rodger. She said,

Once again, we are grieving over deaths and devastation caused by a young man who was sending up red flags for danger that failed to produce intervention in time to avert tragedy. In this case, the red flags were so big the killer's parents had called police ... and yet the system failed.[99]

Some California lawmakers called for an investigation into the deputies' contact with Rodger on April 30, at which time the California gun ownership database reflected the fact that Rodger had bought at least two handguns. Deputies did not check the database, nor did they view the YouTube videos that had prompted Rodger's parents to contact them.[100] In September 2014 California legislators in the California State Legislature passed a red flag law to enable judges to have guns seized from persons who are a danger to themselves or to others.[101] It was subsequently signed into law by Governor Jerry Brown.

Misogyny

The attack sparked discussion of broader issues of violence against women and misogyny.[102][103] Rodger frequented online forums such as PUAHate and ForeverAlone, where he and other men posted misogynistic statements, and described himself online as an "incel" – a member of an online subculture based around its members' perceived inability to find a romantic or sexual partner.[104][105][106] Rodger wrote that after purchasing his first gun he "felt a new sense of power. I was now armed. Who's the alpha male now, bitches? I thought to myself, regarding all of the girls who've looked down on me in the past."[107] He also described his plan to invade a sorority house,[108] writing, "I will slaughter every single spoiled, stuck-up, blond slut I see inside there. All those girls I've desired so much. They have all rejected me and looked down on me as an inferior man."[109] According to the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism at the Hague, these attacks were an act of misogynist terrorism.[6]

Writer M.E. Williams objected to Rodger being labeled the "virgin killer", saying that implies that "one possible cause of male aggression is a lack of female sexual acquiescence".[110] Amanda Hess, writing for Slate, argued that although Rodger killed more men than women, his motivations were misogynistic because his reason for hating the men he attacked was that he thought they stole the women he felt entitled to.[111] Writing for Reason, Cathy Young countered with "that seems like a good example of stretching the concept into meaninglessness – or turning it into unfalsifiable quasi-religious dogma" and wrote that Rodger also wrote many hateful messages about other men.[112]

In Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny feminist academic Kate Manne analyzed the many arguments presented by Young, Mac Donald, and other media commentators to the effect that Rodger could not have been a misogynist because (among other reasons) he was sexually attracted to women, his hateful rhetoric was ultimately the result of mental illness, Rodger loved his mother and hence did not evince a psychological hatred of all women, and he murdered more men than women as an example of a no true Scotsman fallacy. In contrast to a narrow definition of misogyny requiring generalized hatred of women with few (or no) exceptions, similar to the virulent antisemitism of Nazi Germany, Manne argued that in practice misogynists tend to selectively target women based on real or imagined violations of patriarchal norms, and that an excessively narrow conception of misogyny "threaten[s] to deprive women of a suitable name for a potentially potent problem facing them."[113]

In some incel communities, it is common for posts to glorify violence by self-identified incels.[114][115][116] Rodger is the most frequently referenced, with incels often referring to him as their "saint" and sharing memes in which his face has been superimposed onto paintings of Christian icons. Some incels consider him to be the true progenitor of today's online incel communities.[117] It is common to see references to "E.R." in incel forums, and mass violence by incels is regularly referred to as "going E.R."[118][119] Rodger has been referenced by the perpetrators or suspected perpetrators of several other mass killings.[115][120] For example, Alek Minassian, who killed 11 and injured 15 in Toronto, Canada, posted on Facebook before the murders: "Private (recruit) Minassian Infantry 00010, wishing to speak to Sgt 4chan please. C23249161. The incel rebellion has already begun! We will overthrow all the Chads and Stacys! All hail the Supreme Gentleman Elliot Rodger!"[121][122][123]

Controversy over publication of Rodger's videos and manifesto

Several news networks limited the use of the "Retribution" video posted by Rodger for fear of triggering copycat crimes.[124] The New Statesman posited that the manifesto may influence a "new generation of 'involuntary celibates'".[125]

Genius.com co-founder Mahbod Moghadam resigned after receiving negative media attention by adding annotations on Genius.com to the manifesto written by Rodger, which he described as "beautifully written". CNN described Moghadam's annotations as "tasteless and creepy",[126] while Genius.com CEO Tom Lehman said in a statement that it "went beyond that into gleeful insensitivity and misogyny."[127]

Depiction in popular culture

- "Holden's Manifesto", an episode of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, is based on this event.[128][129]

- Rodger was mentioned several times in the Criminal Minds episode "Alpha Male".[130]

- Chanel Miller recounts her experience as a student at UCSB during the event in her 2019 memoir Know My Name.[131]

- The 2023 science fiction film The Beast features a character, played by George MacKay, inspired by Rodger. The film contains re-creations of Rodger's YouTube videos.[132]

See also

- List of homicides in California

- List of mass shootings in the United States

- List of rampage killers in the United States

- Thor Nis Christiansen, a serial killer targeting young women residing in the same area from 1976 to 1977

References

- ^ "Elliot Rodger manifesto outlines plans for Santa Barbara attack". The Sydney Morning Herald. May 25, 2014. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ Dorell, Oren; Welch, William M. (May 26, 2014). "Police identify Calif. shooting suspect as Elliot Rodger". USA Today. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ a b Lovett, Ian; Nagourney, Adam (June 15, 2014). "Video rant, then deadly rampage in California town". The New York Times (published May 24, 2014). Archived from the original on June 25, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ Candea, Ben; Mohney, Gillian (May 24, 2014). "Santa Barbara Killer Began By Stabbing 3 in His Home". ABC News. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ a b Sherwell, Philip (May 24, 2014). "California drive-by shooting: 'Son of Hunger Games assistant director' Elliot Rodger suspected of killing six". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ a b DiBranco, Alex (February 10, 2020). "Male Supremacist Terrorism as a Rising Threat". International Centre for Counter-Terrorism. The Hague. Archived from the original on April 20, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

No misogynist killer articulated the terroristic intention behind his selected target more clearly than 22-year-old Elliot Rodger, who set out on his 'War on Women' to 'punish all females for the crime of depriving me of sex.' The autobiography he left behind—which has been taken as a manifesto for the incel ideology—spells this out.

- ^ United States Secret Service National Threat Assessment Center (March 2022). Hot Yoga Tallahassee: a Case Study of Misogynistic Extremism (Report). Department of Homeland Security. p. 4. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Brugger, Kelsey (February 20, 2015). "Elliot Rodger Report Details Long Struggle with Mental Illness". Santa Barbara Independent. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b c Serna, Joseph; Mather, Kate; Covarrubias, Amanda (February 19, 2015). "Elliott Rodger, a quiet, troubled loner, plotted rampage for months". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "UC Santa Barbara shooter planned killings for months". Los Angeles Daily News. February 20, 2015. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Abdollah, Tami (February 19, 2015). "Man in Santa Barbara rampage sought ways to silently kill". Associated Press. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Parents of Santa Barbara Killer Rushed to Intervene, But Too Late". ABC News. May 25, 2014. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Massarella, Linda; Rosenbaum, Sophia; Greene, Leonard (May 25, 2014). "The vile manifesto of a killer". New York Post. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Sophia; Fears, Danika (May 30, 2014). "'And then I realized I'm bleeding': Survivor of the killer virgin". New York Post. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Exclusive: Santa Barbara Killer Smiled Before Shooting, Survivor Says". ABC News. May 30, 2014. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Woolfe, Nicky (February 20, 2015). "Chilling report details how Elliot Rodger executed murderous rampage". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 14, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Lloyd, Jonathan; Yamamoto, Jane (May 24, 2014). "Witness: Gunman Fired Into Deli Crowd in Drive-By Rampage". NBC Los Angeles. Archived from the original on June 16, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Solnit, Rebecca (May 23, 2015). "One year after the Isla Vista massacre, a father's gun control mission is personal". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "See It: Victims flee from Santa Barbara killer Elliot Rodger inside deli". New York Daily News. May 25, 2014. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Moffitt, Mike (February 20, 2015). "Isla Vista killer practiced stabbing pillows, researched Nazis". SFGate. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Ellis, Ralph; Sidner, Sara (May 27, 2014). "Deadly California rampage: Chilling video, but no match for reality". CNN. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Mendoza, Martha; Pritchard, Justin (May 25, 2014). "Denied again by people he hated, gunman improvised". Associated Press. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Brugger, Kelsey (June 30, 2015). "UCSB Student Files Lawsuit Over May 23 Attack". Santa Barbara Independent. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Giana, Nicky (February 19, 2015). "Timeline of Isla Vista Massacre Reconstructs a Murderous Sequence". Noozhawk. Archived from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Sokmensuer, Harriet (June 13, 2023). "Remembering the 6 Student Victims of the 2014 Isla Vista Killings". People. Archived from the original on March 26, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Isla Vista investigative summary". Los Angeles Times. February 19, 2015. Archived from the original on April 5, 2024. Retrieved April 4, 2024.

- ^ Mineiro, Megan; Yelimeli, Supriya (February 20, 2015). "Sheriff Releases Report Detailing Events, Investigation of 2014 I.V. Mass Murder". Daily Nexus. Archived from the original on June 16, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Santa Barbara shooting suspect feared police would foil attack". Chicago Tribune. May 25, 2014. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ Himes, Thomas (May 24, 2014). "Hundreds gather Saturday night to remember Santa Barbara shooting victims". Los Angeles Daily News. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ Jones, Charisse (May 26, 2014). "Day of mourning planned in Santa Barbara after rampage". USA Today. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ Reyes, Emily Alpert; Mozingo, Joe (May 23, 2015). "Isla Vista rampage victims remembered". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Plait, Phil (May 27, 2014). "#YesAllWomen". Slate. Archived from the original on June 12, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- ^ a b Grinberg, Emmanuela (May 27, 2014). "Why #YesAllWomen took off on Twitter". CNN. Archived from the original on May 28, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ Dempsey, Amy (May 26, 2014). "#YesAllWomen hashtag sparks revelations, anger, debate in wake of California killing spree". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on July 26, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- ^ Song, Jasmine (May 26, 2014). "Trending: #YesAllWomen as women fire back against Elliot Rodger's shooting spree". WTOP News. WTOP-FM. Archived from the original on August 17, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ^ "#YesAllWomen". Twitter. July 2, 2014. Archived from the original on July 31, 2009. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ Valenti, Jessica (May 28, 2014). "#YesAllWomen reveals the constant barrage of sexism that women face". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ Bootle, Emily (October 14, 2022). "Are the 1975 geniuses, or simply mediocre?". New Statesman. Archived from the original on November 26, 2022. Retrieved November 19, 2022.

Healy turns his attention to a "supreme gentleman" – the nickname for the so-called incel Elliot Rodger

- ^ "Toronto van attack: What is an 'incel'?". BBC News. April 24, 2018. Archived from the original on November 23, 2022. Retrieved November 19, 2022.

Facebook confirmed to the BBC that Minassian was the author of a post which read in part: "The Incel Rebellion has already begun! We will overthrow all the Chads and Stacys! All hail the Supreme Gentleman Elliot Rodger!"

- ^ "How Elliot Rodger went from misfit mass murderer to 'saint' for group of misogynists — and suspected Toronto killer". Los Angeles Times. April 26, 2018. Archived from the original on August 22, 2019. Retrieved November 19, 2022.

In November, Reddit banned the discussion board r/incels for promoting violence against women. On the subreddit, Rodger was often called "Saint Elliot."

- ^ Molloy, Antonia (May 26, 2014). "California killings: Elliot Rodger's parents heard news of massacre on radio as they raced to stop their son". The Independent. Archived from the original on August 2, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ Flynn, Mike (May 25, 2014). "Elliot Rodger shootings in Isla Vista, Santa Barbara, California. Elliot Rodger is the son of one of the directors who worked on 'Hunger Games'". Covered Globe. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ "Li Chin Tye - IMDb". IMDb. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 9, 2023.

- ^ Brown, Pamela (May 27, 2014). "California killer's parents frantically searched for son during shooting". CNN. Archived from the original on May 28, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ Duke, Alan (May 27, 2014). "California killer's family struggled with money, court documents show". CNN. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ Habibu, Sira (May 27, 2014). "'Unloved' killer was adored". The Star Online. Malaysia. Archived from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ^ "Inside Santa Barbara Killer's Manifesto". ABC News via Good Morning America. May 25, 2014. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ^ Allen, Nick (May 27, 2014). "'Virgin killer' Elliot Rodger planned to murder his family". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Nagourney, Adam; Cieply, Michael; Feuer, Alan; Lovett, Ian (June 1, 2014). "Before Brief, Deadly Spree, Trouble Since Age 8". The New York Times (published June 2, 2014). Archived from the original on June 3, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ a b "Isla Vista Mass Murder – May 23, 2014 – Investigative Summary" (PDF). Santa Barbara County Sheriff's Office. February 18, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 20, 2015. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ Duke, Alan (May 27, 2014). "Timeline to 'Retribution': Isla Vista attacks planned over years". CNN. Archived from the original on May 28, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ^ a b Mendoza, Martha; Garcia, Oskar (May 25, 2014). "Suspect in California rampage blamed aloof women". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ a b "The secret life of Elliot Rodger: ABC 20/20 special edition". ABC News. June 27, 2014. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ a b Mozingo, Joe; Covarrubias, Amanda; Winton, Richard (May 25, 2014). "Isla Vista shooting suspect's videos reflect cold rage". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ Alcindor, Yamiche; Welch, William M. (May 26, 2014). "Parents read shooting suspect's manifesto too late". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ Firger, Jessica (May 26, 2014). "Mental illness in spotlight after UC Santa Barbara rampage". CBS News. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "Isla Vista suspect allowed to buy guns despite emotional problems". Los Angeles Times. May 27, 2014. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "How I tried to help Elliot Rodger". BBC. July 8, 2014. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ a b c Blake, Mariah (June 14, 2014). "Read: The Police Report From the Incident That Spurred Elliot Rodger to Mount His Killing Spree". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Mather, Kate; Winton, Richard (June 11, 2014). "Police took no action in reported attack by Elliot Rodger in 2013". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Duke, Alan (May 27, 2014). "Timeline to 'Retribution': Isla Vista attacks planned over years". CNN. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Salonga, Robert (May 30, 2014). "Santa Barbara rampage: San Jose victim posthumously cleared of 'candle theft'". Mercury News. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Isla Vista Killer's April 30 Check-Up". Santa Barbara Independent. May 29, 2014. Archived from the original on June 16, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Caroline, Bankoff (May 26, 2014). "UCSB Shooter's Parents Tried to Stop Him". New York Magazine. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b "Cops knew about Santa Barbara attacker's videos, but didn't watch them". CBS News. May 30, 2014. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ G. Fitzsimmons, Emma; Knowlton, Brian (May 25, 2014). "Gunman Covered Up Risks He Posed, Sheriff Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 22, 2023. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Deputies Who Made Welfare Check on UCSB Killer Elliot Rodger Cleared". NBC News. May 31, 2014. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "The Manifesto of Elliot Rodger". The New York Times. May 25, 2014. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Dalrymple II, Jim (May 25, 2014). "The Bizarre And Horrifying Autobiography Of A Mass Shooter". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Beekman, Daniel (May 26, 2014). "Elliot Rodger wrote manifesto on his hate for women and his vindictive scheme prior to deadly rampage". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "California Gunman's Apparent 'Manifesto' Details Hatred of All Women". NBC News. May 24, 2014. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Duke, Alan (May 27, 2014). "Five revelations from the 'twisted world' of a 'kissless virgin'". CNN. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Inside Santa Barbara Killer's Manifesto". ABC News. May 24, 2014. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b "Cops never saw shooter's disturbing videos before spree". New York Post. May 25, 2014. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Pengelly, Martin (May 25, 2014). "California killings: UK-born Elliot Rodger blamed for deaths". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Caspian Kang, Jay (May 28, 2014). "The Online Life of Elliot Rodger". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Transcript of video linked to Santa Barbara mass shooting". CNN. May 27, 2014. Archived from the original on June 24, 2023. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Mozingo, Joe; Covarrubias, Amanda; Winton, Richard (May 25, 2014). "Isla Vista shooting suspect's videos reflect cold rage". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 16, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Theriault, Anne (May 25, 2014). "The Men's Rights Movement Taught Elliot Rodger Everything He Needed to Know". Huffpost. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Woolf, Nicky (May 30, 2014). "'PUAhate' and 'ForeverAlone': inside Elliot Rodger's online life". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Gell, Aaron (May 24, 2014). "Online Forum For Sexually Frustrated Men Reacts To News That Mass Shooter May Be One Of Their Own". Business Insider. Archived from the original on November 20, 2023. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Infographic: Elliot Rodger's laptop search history: Nazis, knives and torture devices". Los Angeles Times. February 19, 2015. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Dobuzinskis, Alex (February 19, 2015). "Online Forum For Sexually Frustrated Men Reacts To News That Mass Shooter May Be One Of Their Own". Reuters. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Gell, Aaron (February 19, 2015). "Report: Man who killed 6 UC Santa Barbara students searched online for ways to silently kill". Fox News. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Duke, Alan (May 27, 2014). "California killer's family struggled with money, court documents show". CNN. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Flores, Byadolfo; Winton, Richard; Mather, Kate (May 30, 2014). "Deputies didn't know Elliot Rodger owned guns, officials say". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Nagourney, Adam (May 25, 2014). "Parents' Nightmare: Futile Race to Stop Killings". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2014. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Allen, Nick (May 27, 2014). "'Virgin killer' Elliot Rodger planned to murder his family". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Family of Santa Barbara Shooter Elliot Rodger Calls Him A 'Monster'". Inside Edition. May 29, 2014. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b "US 'Virgin Killer' Elliot Rodger plotted to slaughter his own family, including his six-year-old brother". Evening Standard. May 27, 2014. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Chasmar, Jessica (May 27, 2014). "Elliot Rodger planned to murder 6-year-old brother, stepmother". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Kaplan, Rebecca (May 25, 2014). "Senator: California shooting should prompt fresh look at gun laws". www.cbsnews.com. Archived from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- ^ "Sen. Blumenthal: It's time to revive the gun control debate". MSNBC. May 25, 2014. Archived from the original on January 7, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- ^ Dennis, Steven (May 25, 2014). "Elliot Rodger Shooting Prompts Feinstein to Blame NRA 'Stranglehold' on Guns". #WGDB blog. Roll Call. Archived from the original on May 26, 2014. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ^ Dennis, Steven (May 25, 2014). "Elliot Rodger Sparks New Call for Mental Health Bill". 218 blog. Roll Call. Archived from the original on May 26, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ "Dad of Santa Barbara Victim Rails Against Son's Death". ABC News. Archived from the original on June 16, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- ^ "California killings: Father of victim shot by Elliot Rodger blames". The Independent. May 25, 2014. Archived from the original on May 1, 2022. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- ^ Kindy, Kimberly (May 27, 2014). "Father of victim in Santa Barbara shootings to politicians: 'I don't care about your sympathy.'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 2, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ Mendoza, Martha; Blood, Michael R. (May 26, 2014). "Elliot Rodger's family tried to intervene before his deadly rampage". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on May 27, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ Lovett, Ian (May 31, 2014). "In Wake of Rampage, Sheriff's Office Faces Concerns about Conduct". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 1, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ Thompson, Don (September 30, 2014). "Gov. Jerry Brown Signs California Gun Restriction". ABC News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 2, 2014. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

- ^ Penny, Laurie (May 25, 2014). "Let's call the Isla Vista killings what they were: misogynist extremism". New Statesman. Archived from the original on May 26, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ Medina, Jennifer (May 26, 2014). "Campus Killings Set Off Anguished Conversation About the Treatment of Women". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 27, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ Mezzofiore, Gianluca (April 25, 2018). "The Toronto suspect apparently posted about an 'incel rebellion'. Here's what that means". CNN. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

- ^ Woolf, Nicky (May 30, 2014). "'PUAhate' and 'ForeverAlone': Inside Elliot Rodger's online life". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

- ^ Dewey, Caitlin (May 27, 2014). "Inside the 'manosphere' that inspired Santa Barbara shooter Elliot Rodger". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

- ^ Solnit, Rebecca (May 23, 2015). "One year after the Isla Vista massacre, a father's gun control mission is personal". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ "Thwarted in his plan, California gunman improvised". CBS News. Associated Press. May 25, 2014. Archived from the original on May 26, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ Garvey, Megan. "Transcript of the disturbing video 'Elliot Rodger's Retribution'". Los Angeles Times. No. May 24, 2014. Archived from the original on November 18, 2014. Retrieved November 26, 2014.

- ^ Williams, Mary Elizabeth (May 27, 2014). "The media scapegoating of Rodger's childhood crush". Salon. Archived from the original on May 28, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ Hess, Amanda (May 29, 2014). ""If I Can't Have Them, No One Will": How Misogyny Kills Men". Slate. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ Young, Cathy (May 29, 2014). "Elliot Rodger's 'War on Women' and Toxic Gender Warfare". Reason.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2014. Retrieved August 3, 2014.

- ^ Manne, Kate (2019). Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny. Penguin Random House. pp. 31–54, 75–77. ISBN 9780141990729. Archived from the original on March 15, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ "Elliot Rodger: How misogynist killer became 'incel hero'". BBC News. April 26, 2018. Archived from the original on May 12, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ a b Branson-Potts, Hailey; Winton, Richard (April 26, 2018). "How Elliot Rodger went from misfit mass murderer to 'saint' for group of misogynists — and suspected Toronto killer". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ Gillies, Rob (March 3, 2021). "Man who used van to kill 10 pedestrians in Toronto guilty". AP News. The Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ Beauchamp, Zack (April 16, 2019). "The rise of incels: How a support group for the dateless became a violent internet subculture". Vox. Archived from the original on October 8, 2019. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ "Incels (Involuntary celibates)". adl.org. Anti-Defamation League. July 30, 2020. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ Hoffman, Bruce; Ware, Jacob; Shapiro, Ezra (2020). "Assessing the threat of incel violence". Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 43 (7): 565–587. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2020.1751459. hdl:10023/24162. ISSN 1057-610X. S2CID 218781135.

- ^ Woolf, Nicky (May 30, 2014). "'PUAhate' and 'ForeverAlone': Inside Elliot Rodger's online life". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ Krishnan, Manisha (March 3, 2021). "'Incel' Toronto van killer found guilty of murdering 10 people". Vice News. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ "'A huge loss': Yonge Street van attack victim Amaresh Tesfamariam missed 'every day'". Toronto.com. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. November 12, 2021. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ Golding, Janice (November 4, 2021). "'It's so sad, heartbreaking': Nurse paralyzed after Toronto van attack dies". CTV News. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Archived from the original on November 4, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ Grove, Lloyd (May 27, 2014). "Should TV News Show Elliot Rodger's 'Retribution' Video?". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on May 28, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ Tait, Amelia (January 31, 2017). "Why we should stop using the phrase "lone wolf"". New Statesman. Archived from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- ^ Gross, Doug (May 27, 2017). "Tech exec fired for comments about California killer". Cable News Network. Archived from the original on January 24, 2023.

- ^ Swisher, Kara (May 26, 2014). "Rap Genius Co-Founder Moghadam Fired Over Tasteless Comments on Santa Barbara Shooting". Recode. Archived from the original on December 3, 2018.

- ^ "The best episodes from all 20 years of Law and Order – SVU". vice.com. October 18, 2018. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- ^ Easton, Anne (October 16, 2014). "'Law & Order: SVU' Recap 16×4: The Quest for Validation". The New York Observer. Observer Media. Archived from the original on October 19, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ "Alpha Male". Criminal Minds. Season 12. Episode 15. March 1, 2017. CBS.

- ^ Miller, Chanel (2019). Know my name : a memoir. [New York, New York]. ISBN 978-0-7352-2370-7. OCLC 1115007919. Archived from the original on February 18, 2022. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Croll, Ben (September 3, 2023). "Director Bertrand Bonello Explains the Shocking, Incel Inspiration for 'The Beast,' Starring Lea Seydoux, George MacKay (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Archived from the original on September 24, 2023. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

External links

- "Transcript of "Elliot Rodger's Retribution"". Los Angeles Times. May 24, 2014.

- 2014 mass shootings in the United States

- 2014 crimes in California

- 2014 murders in the United States

- Attacks in the United States in 2014

- Deaths by firearm in California

- Deaths by stabbing in California

- Drive-by shootings

- History of Santa Barbara County, California

- Incel-related violence

- Knife attacks in the United States

- Mass murder in 2014

- Mass murder in California

- Mass shootings in California

- Mass shootings in the United States

- Mass stabbings in the United States

- Mass shootings involving Glock pistols

- Massacres in the United States

- Massacres in 2014

- May 2014 crimes in the United States

- May 2014 events in the United States

- Murder–suicides in California

- Race and crime in the United States

- Spree shootings in the United States

- Stabbing attacks in 2014

- Vehicular rampage in the United States

- Violence against women in California